The day began with a comfortably low temperature of 17oC before rising to a high of 28oC. In the crushing crowd outside the Lincoln Memorial, it would seem unbearably hot to many. But fevers were raised by more than the beat of sun and thirsts were quenched by words more invigorating that the water of the Reflecting Pool on August 28, 1963.

And on the very day that Martin Luther King Jnr chose to ad-lib as he addressed the massed crowds at the Freedom March in Washington DC, Emily Hoffert and Janice Wylie were murdered. As he watched King’s historic oration, the African-American man George Whitmore Jnr could not know that he would be beaten by Manhattan police, forcing him to submit to confession and hence arrest for the double murder of the two white women dubbed the “career girl murders”.

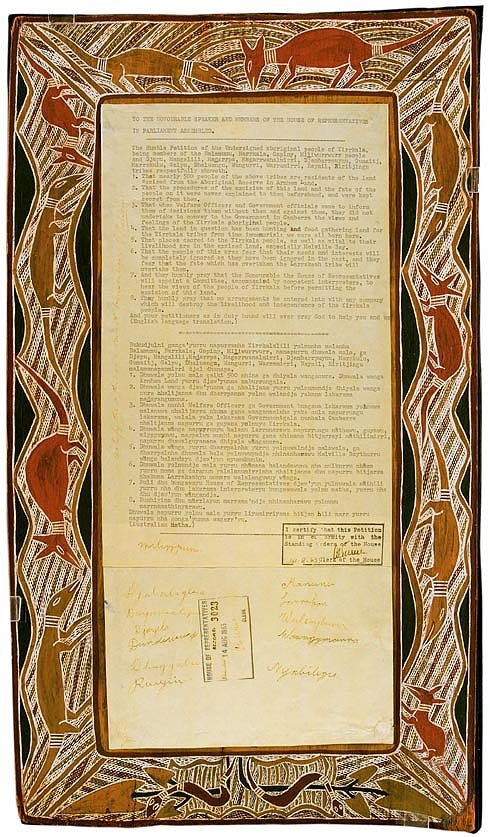

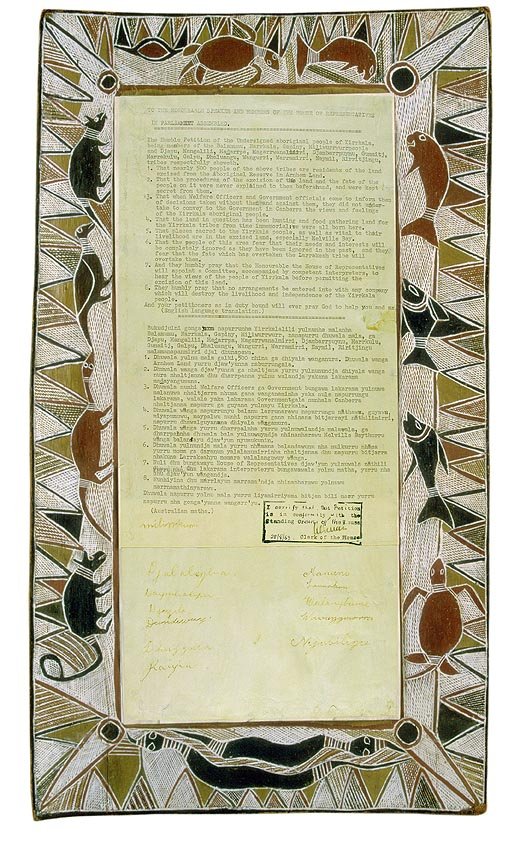

Roughly 15,940 km away, just a few hours earlier in much cooler late winter climes, the second of two petitions were presented to and accepted by the Australian Parliament, protesting against the Commonwealth’s acquisition of 300 km2 of land belonging to the Yolgnu people of the Yirrkala nation in Arnhem land. The Yirrkala Bark Petitions, as they have come to be known, were not the first documents presented to the Commonwealth by indigenous Australians, but they did mark the first that were accepted from the indigenous people of Australia. These petitions became the ground upon which native title was built.

Although a Parliamentary Select Committee was formed to investigate the claim of the Yolgnu people, which recommended that the people should receive recompense for their loss both in terms of land and royalties and other monies, the Commonwealth chose instead to simply annexe a portion of the Aboriginal reserve so that it could be freely mined. The Yirrkala nation received not a cent, despite fighting through the Supreme Court. The concept of terra nullius was first applied in the legal judgment and had broad impacts for many years until Mabo in 1992.

Literally half a world away, black men were making monumental statements about freedom, human rights and respect. Both statements made in Westernized nations, supposedly civilized countries. It is the first time that either the United States or Australia has taken note of its black people. In the case of America, a sheer force of numbers forced the nation to turn and listen. As for Australia, the black man had presented something acceptable to its “master”, a document in a format that the parliament would accept. Both were acts of defiance, both were heard and both were ignored.

Although King’s speech moved Americans to consider race relations and integration of schools and workplaces, the plight of George Whitmore showed how far they had to go. Similarly, the ignored recommendations of the Select Committee demonstrated how the system will simply pretend to tick the boxes for the black man and still provide an outcome that suits the non-indigenous status quo.

Today marks the fiftieth anniversary of both King’s unforgettable speech and the presentation of the second Yirrkala Bark Petition to the Australian Parliament. Taking stock, the Stronger Futures legislation, built on the back of the Northern Territory Intervention, still marginalizing the Australian Aborigine, treats him as a child. Taking stock, we see an America where a young black man is demonized after he dies defending himself after he is stalked by another man in a car.

Whilst race relations in Westernized nations have progressed to allow black and white to eat from the same table and work at the same jobs, they are still not afforded the same justice by a Euro-centric, Christian-based judicial system. The church and state may never be meant to meet, but the judicial structure and concepts of morality are built upon the premise of a Christian morality and Western social norms. With those norms, come the ability to corrupt the processes through selective presentation of evidence or delay in dealing justice. The traditional land owners of the Australian continent have been waiting more than 200 years for justice, for recompense for the falsity of terra nullius, for the promised opportunity that the white man offered but has never properly delivered.

And in America, the black man awaits the day when he too can expect the same justice and consideration as a white man. He waits to see when he will be able walk without others fearing him simply because of his colour, his hoodie, his youth.

Luther King had a dream, perhaps a vain dream shared by Miguel Cervantes. But you see, I like the Man of La Mancha, because he dreamed big, he dreamed honourably, he dreamed without fear. I like the tale because the man who recovered from his malaise awoke to the horror of reality and the truth of the corrupted spirit. Martin Luther King felt the burning heat of such corruption of the spirit and the people of Yirrkala learned not to trust the white man. The dream of peace between black and white is threatened not by madness, but by a real foe that proclaims a truth of equality under a Christian system that rationalizes maltreating the marginalized through some corrupted sense of right. There is a dream dreaming us, but as Bakchos says, we are living it badly. True equality can only come when black Americans and Australian Aborigines are able to walk the street or go to a shop without anyone assuming the worst of them.

The foe lies within. We ourselves are branding our dream of equality impossible. King must be watching from his corner wondering how his dream could still not be realized, either in America or Australia. Until colour is no impediment to respect, no man of colour can expect anything better.