To every thing there is a season, and a time to every purpose under the heaven:?

A time to be born, and a time to die; a time to plant, a time to reap that which is planted;?

A time to kill, and a time to heal; a time to break down, and a time to build up;?

A time to weep, and a time to laugh; a time to mourn, and a time to dance

A time to cast away stones, and a time to gather stones together; a time to embrace, and a time to refrain from embracing;?

A time to get, and a time to lose; a time to keep, and a time to cast away;?

A time to rend, and a time to sew; a time to keep silence, and a time to speak;

A time to love, and a time to hate; a time of war, and a time of peace.

I like Peter Seeger’s song based upon the Book of Ecclesiastes. It speaks of the appropriateness of our actions in daily life and the cycle from birth to death. It acknowledges that from the time we are born to the day we pass into whatever lies beyond the veil of death, there is reason for everything that we do, even to kill. It seems anathema to the sixth commandment, given to Moses on Mount Sinai and the edict not to kill, that taking the life of another without due cause was murder and held no virtue.; killing in times of war, as an act of self-defence or as an act of capital punishment was differentiated in the Tanakh and hence was considered less reprehensible.

On this day ninety-nine years ago, a thirty-four year old Turkish commander by the name of Mustafa Kemal watched as the Australia and New Zealand Army Corps descended upon the shores of Gallipoli. A seasoned military man who had participated in the Turkish Revolution in 1908 and the war against Italy in Libya in 1911-12, Mustafa had risen the rank of Lieutenant-Colonel and was chief of staff of army on the Gallipoli Peninsula.

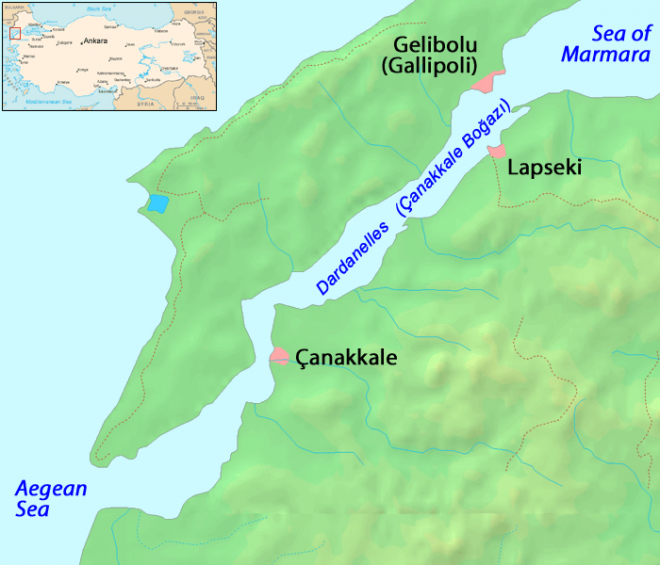

On the day on which so many young men became grist to the European war mill far from home in a foreign land, Mustafa was proved right in his unheeded argument that Allied troops would attempt to take this crucial strategic peninsula that overlooked the narrow strait of the Dardanelles in Turkey connecting the Aegean Sea and the Sea of Marmara. A total of 11,400 ANZAC men were lost in the 10 month campaign for control of this 61 kilometre long strait that, which at its widest is only 6 kilometres.

Ataturk, a name given to Mustafa Kemal in 1934 acknowledging his role of “father” of his nation, saw the allied troops defeated and retreat from his homeland. Whilst he subsequently saw defeat in Palestine in 1918, Ataturk retained virtue as the supreme commander and Turkey’s first president. He realized when it was time to fight and when it was time make peace, pulling his people into a modern age through socio-economic, political and legal reforms.

In the same year in which he was acknowledged Ataturk, Mustafa held out the hand of friendship and peace in his tribute to those ANZACs who lost their lives on the Gallipoli peninsula with his exceptional gesture, in which he calls all those who died “heroes”:

Those heroes that shed their blood and lost their lives… You are now lying in the soil of a friendly country. Therefore rest in peace. There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets to us where they lie side by side now here in this country of ours… you, the mothers, who sent their sons from faraway countries wipe away your tears; your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace. After having lost their lives on this land they have become our sons as well.

A time of war, and a time of peace. And amongst them were a people, subjugated by a constitution which excluded them from recognition in their traditional homeland – the Australian Aborigines. The graves of four Australian Indigenous servicemen hold the bodies of those Aboriginal diggers who were considered equal only in their ability to die for an Empire that had been forced upon them and treated them as less than human. Indeed, in 1909 the Aborigines Protection Act provided for camps in which the deciminated population of indigenous Australians would be left to “become extinct”, as eugenics theory theorized that these people were something less than human. It is ironic that in enlisting troops, the race of each new recruit was not recorded, despite the ongoing repression of Aboriginal rights. Good enough to fight, good enough to be held in the bosom of the Turkish people, good enough to be remembered by one of the great men in history.

On this Anzac Day, which 100 years ago did not exist, Blak and Black acknowledges all those who lost their lives in the futility of the Gallipoli campaign: New Zealanders, Turks, Indians, Britons, French and Australians including the Aborigines of Australia and Maoris of Aotearoa. That battle is done.

Lest we forget those victims of greed and hypocrisy.