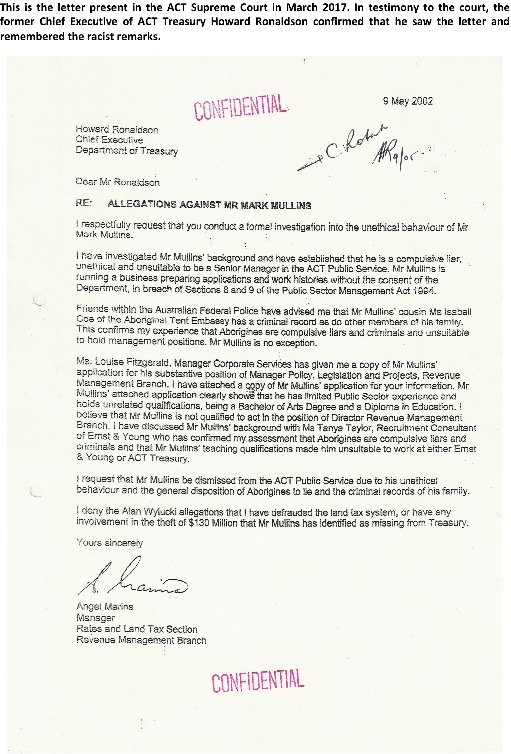

Some days demand that we pause to reflect on an event on the same date in the past. For Blak and Black that day is 9 May and this year marks 20 years since Angel Marina wrote his now widely recognised letter of racism against the ACT Government’s then most senior Indigenous employee.

That letter, exhorting the benefits to the author of having “friends in the Australian Federal Police” has been the genesis of extensive cruelty to the victim and his family. Not satisfied with the destruction they had wrought upon the family, the ACT Government used the outcome of a 2013 hearing in the ACT Administrative Appeals Tribunal (ACTAAT) to file an allegation of fraud with the AFP regarding a supposed affidavit submitted by Bakchos in advance of the proceedings. The AFP charged Bakchos with fraud. Ultimately Bakchos won 16-0 in a jury finding in the ACT Supreme Court in 2017.

Many would think that’s the end. Bakchos won. But did he? Did his family suddenly resume their usual lives? Was the time lost worrying about the fit-up created by the ACT Government and allowed by the AFP somehow restored without the pain and trauma? No, it was not, it could not.

The jury in March 2017 were confronted by a prosecution case that failed to be able to demonstrate the most basic aspects of the case. The original of the affidavit supposedly submitted to the ACTAAT was nowhere to be found. What’s more, Bakchos’ lawyers were still billing him for preparation of an affidavit three weeks after the supposed date it was lodged with the Tribunal. Tu Pham had to be recalled to the stand to clarify testimony when it was demonstrated that she had not been entirely frank with the court. Howard Ronaldson testified that he recalled the 9 May 2002 letter being delivered by Marina that very day and sending the original on to Corporate Services for investigation, providing a copy for the victim. Holes in the prosecution case that you could drive trucks through, allowed by “friends in the AFP”.

About a week ago someone on Twitter noted with shock that a person she knew had been charged with murder. The tone of the tweet and replies indicated that she was willing to accept that police only charge someone with murder if they believe they can prove the offence. The presumption of innocence is a crucial aspect of the Australian legal system, yet many are prepared to judge someone who is charged without the accused having had the opportunity for a fair trial

What every person needs to understand is that police and prosecutors have at their disposal essentially unlimited funds to pursue an investigation and conviction; most accused have far less. There is absolutely zero consequence to an investigator or prosecutor for laying charges that cannot be proved. The choice to take a case to court is entirely at the discretion of the Department of Public Prosecutions. There is little personal risk, no family impact, no loss of income, no employment consequences. Conversely, an accused faces immediate ostracization from family, friends and colleagues, many of whom assume the worst. The accused must find the funds to fight a wrongful charge … worse yet, they must prove a fit-up, if that’s what has happened. The accused faces losing everything they cherish and own, let alone the potential for an extensive custodial sentence. Bakchos lost many friends and acquaintances. One has had the good grace to apologise and rebuild the relationship.

As spectators, perhaps jurors, assessing charges brought against an accused, we should always bear in mind that police and prosecutors carry virtually no risk if they lose the court case. As the enforcers of law, they are assumed to be bastions of good, honest and true. But just as an accountant, doctor or mechanic can be fallible, so can police. They can make mistakes, they can miss evidence … and they can be corrupt. Self-interest drives people, regardless of industry to look for the quickest resolution to a problem. It’s not always the safest or the fairest. People just want a problem to go away, not always appreciating the longer-term consequences. Police can and do accept and embellish the lies of corrupt individuals, agents and agencies. As members of the public, each of us needs to question every single piece of evidence, every utterance, every assertion made by the AFP or any other police force to ensure that justice truly is carried out. If the police are prepared to lie on any single point of evidence, why should you, the public, accept anything else they say without scrutiny?

Without a jury trial, Bakchos faced a maximum of 10 years in jail per charge with the potential the each could be served consecutively. He faced the potential of never being released from jail. Because the ACT Government fitted him up and their friends in the AFP went along with the narrative.

And it all started with one racist letter on 9 May 2002 about one Aboriginal man, who was doing nothing more than trying to serve the people of the Australian Capital Territory as their Commissioner for Revenue. It’s long past time that those responsible for the fit-up and loss in court in 2017 faced charges themselves. Justice will only be served when there is transparency and accountability.