“Item quilbet presumitur innocens nisi probetur nocens.”

Jean Lemoine (aka Johannes Monarchus), 4th century French jurist.

In a world hurtling toward greater unrest and division, the importance of the presumption of innocence must not be lost. Laws that strip this protection from an accused, risk disadvantaging those who are falsely accused. The Social Security and Other Legislation Amendment currently under debate, with its provisions for the Home Affairs Minister to cease Centrelink payments to an accused who has not faced a trial or judgement, risk condemning a wrongly accused person and forcing them into an untenable situation. It is not acceptable.

The presumption of innocence is a core tenet within criminal law, described as its “the golden thread”. Espoused by British lawyer Sir William Garrow in 1791 in the Old Bailey, its origins are far longer and represent consideration of how the criminal process may be corrupted, intentionally or not, to the disadvantage of an accused.

The heritage of the maxim, as suggested by the opening Latin quote, is far older than Garrow. It is mentioned neither within the Magna Carta in 1215 nor the English Bill of Rights passed in 1689. A statement regarding an accused’s right to be presumed innocent until proved otherwise was included in the French Declaration of the Rights of Man and Citizen in 1789 and earlier by Beccaria

“Either the crime is certain or it is not; if it is certain, then no other punishment is called for than what is established by law and other torments are superfluous because the criminal’s confession is superfluous; if it is not certain, then according to the law, you ought not torment an innocent because such is a man whose crimes have not been proven.”

Dei delitti e delle pene, Cesare Beccaria, 1764

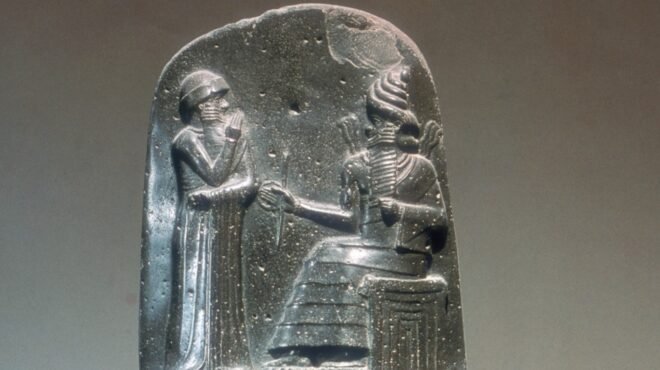

Whilst the presumption of innocence is not explicitly stated in early accounts and tests, there are clear inferences. The earliest such inference is found in the Babylonian Code of Hammurabi, dating from 1750 BCE. A list of 282 laws from the ancient Sumerians written in Akkadian, the third reads:

“If any one bring an accusation of any crime before the elders, and does not prove what he has charged, he shall, if it be a capital offense charged, be put to death.”

In Jewish law, the Talmud asserts that making an unjustified accusation has the potential to lead to false testimony and slander. It is a serious sin and places the burden of proof upon the accuser. Similarly, Islam condemns all forms of accusation, including suspicion, requiring that any accusation be substantiated.

Proof of wrongdoing in Europe in the middle ages often relied upon proof by ordeal; did the woman accused of witchery drown or float; did the man accused of treason confess under torture. It took only one accusation with absolutely no proof to consign a person to a terrifying and often painful “test”. The presumption was that the accused was guilty unless they passed the ordeal.

The transition to a presumption of innocence necessitated abandoning torture as a test, instead placing the burden of proof on the accuser. In the mid twelfth century, a canon lawyer by the name of Paucapalea concluded in his Summa Rolandi, that as God had first to ask Adam of his sin in eating the apple from the tree in Eden, and also sought confirmation from the snake and Eve, so must people abide by the same precepts. By placing God at the heart of the matter, the accused was afforded at least two witnesses before the ordeal.

Not all legal minds agreed. The Ius commune, existing from Roman times, already argued for the presumption of innocence, but not all believed a trial was required. Particularly heinous crimes, especially those that offended God, could be ruled upon without trial. However, over the ensuing half century, jurists adopted Paucapalea’s argument and all defendants were afforded a trial, although not all avoided torture.

Johannes Monarchus argued that a defendant must be presented to a court lest an injustice be served. As God had summoned Adam, so must the court summon an accused, and in being summoned, their innocence must be assumed. The accused must be afforded due process and a trial. Similarly, as God had pronounced a judgement, so must the court.

Monarchus also asserted that justice was blind to the religious beliefs of the individual. The hold of the Church was strong and many Christian legal representatives refused to assist or hear cases from Jews, until Pope Paul II confirmed the absolution of judges, notaries and scribes following a petition from the Habsburg Emperor Frederick III. Later Popes decreed that Jews must be given the names of their accusers, be able to challenge the allegations, receive financial assistance and have an advocate, with the option to appeal to Rome if refused. Notably, English common law did not acknowledge the right of a defendant for treason to legal counsel until 1696.

Sometime between 1601 and 1603, Prospero Farinacci published his Praxis et theorica criminalis. A judge noted for his harsh sentences, his work is a seminal legal text that asserted that not even the Pope had the authority to deny an accused a defence and an opportunity to prove their innocence. So committed to the concept was he that he defended the most famous murderer of that day, Beatrice Cenci, who with her siblings and two others, killed her violent and abusive father. Whilst Beatrice was executed, her twelve year old brother was spared on the argument of Farinacci.

English common law, practiced in many Commonwealth or English speaking countries is built upon decisions made by judges, developing a body of case law which guides subsequent judicial decisions. It differs from European civil law systems, which derive from Roman law, from which inviolable codes are established, placing far less reliance on prior cases. Despite the differing origins and functional variations, each has adopted the presumption of innocence as a core element of their system.

The ubiquity of the presumption of innocence across legal systems indicates the reason for its inclusion in the UN Declaration of Human Rights and the International Criminal and Civil Protection of Rights. This foundational concept borne in the aftermath of World War II has afforded those accused of the very worst offences the right to face their accusers and defend their character. It is a fundamental right intended to protect against malicious and unprovable allegations and subsequent loss of reputation. It is by no means perfect. There are those who still assume that because and accusation has been made that it must be true; mud sticks, even when the allegation has been successfully refuted. Worse yet, malicious accusations in the modern world often go unpunished. Yet the importance of this golden thread cannot be denied in affording each person the right to be given a trial and to face their accuser.

To deny a defendant the right of a trial to know the name of their accuser and the specifics of the accusation is both unfair and unethical. And to deny a defendant the financial means to live in the face of unproved accusations is a clear breach of the right to be presumed innocent. The passing of the Social Security and Other Legislation Amendment will remove the most important and fundamental of protections, most importantly for those who are politically engaged. It must not pass in its current form.