“No one shall be subject to cruel, inhuman or degrading punishment.” This statement of Article 7 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights is part of what Michael Ignatieff [i] aptly calls “the judicial revolution” in human rights since 1945. Other critical international documents of the revolution include the Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Geneva Convention of 1948, the revision of the Geneva Convention of 1949 and the international convention on asylum of 1951.

Covenants without swords are but words, Thomas Hobbes famously wrote. What kind of revolution is marked by so many words that lack the backing of swords? The International Covenant, unlike the Universal Declaration, is a legally binding treaty among nations. A Human Rights Committee has the authority to adjudicate violations that are brought before it. The legally binding nature of this and other human rights treaties is another indication of the rights revolution. To say that human rights are legally binding, however, is not to say that there is an authoritative agent with the power to hold sovereign states to the law. For this and many other reasons, the human rights revolution is far from complete and its capacity to come closer to realising its aims is widely questioned, especially outside the now highly organised communities of human rights activists. Moreover, what would count as a successful completion of the human rights revolution is by no means clear or clearly established in either the theory or the practice of human rights in the international arena.

Yes, the human rights revolution is a long way from being won and on many fronts, including Australia, it is in wholesale retreat. Why? Apathy is the short answer, basking in the reflected glory of our alleged egalitarian society is the longer answer, but regardless of which answer we chose, you, I, our families and friends are the losers unless we start asking our politicians some very hard questions.

This site has been established in part to help foster a better understanding within the community of the plight and the needs of Indigenous and other disadvantaged Australians. Its message is about peace and mutual respect. That is what I stand for.

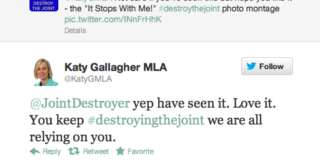

The reason for this post is that over the last few days I have received a number of emissaries from the ACT Government threatening me with legal and other (from someone who uses the acronym PTT on public discussion boards) action if I don’t remove my posts on Angelique and Pat. What have they got to hide?

In support of the human rights revolution and my right to freedom of speech I have decided to provide some of the source documents which form the basis of my post titled Angelique, Pat and the rule of law.

As I mentioned in my post, Pat is a former Commissioner for ACT Revenue whose only crime apart from the colour of his skin was to ask that ‘white’ people hold themselves to the same level of accountability as they hold ‘black’ people to.

Pat’s problems arose when he wrote to the Chief Minister of the ACT Mr Jon Stanhope, advising him that there had been a break down in the rule of law within the ACT Public Service and that corruption was running unchecked. Pat was eventually sacked for writing that letter. Jon Stanhope denies ever receiving it, ACT Treasury likewise. Problem: the ACT Ombudsman (Professor John McMillan) via one of his senior investigators references the letter. In a letter to Pat dated 26 June 2005, Director of Investigations Mr Chris Roberts, very clearly stated that the ACT Department of Treasury referenced Pat’s letter of 27th June 2003 to the Chief Minister (Mr Jon Stanhope) and the Chief Executives (Mr Mike Harris) response, dated 4 July, 2003.

Pat’s letter and the reply from Mr Harris were subpoenaed in 2006. The ACT Government did not provide either the letter or the response. I have requested the letter under the ACT’s Freedom of Information Legislation without success. Ms. Isabelle Coe, famous for her unyielding efforts at the Aboriginal Tent Embassy and Pat’s cousin, wrote to the ACT Chief Police Officer in 2006 about the missing letters. To date there has been no response from ACT Policing.

Until recently the ACT was the only jurisdiction in Australia in possession of any meaningful human rights legislation. However, if the very body that enacts this type of legislation then ignores its provisions when they become uncomfortable, then it becomes nothing more than window dressing and serves no other purpose than as a smoke screen designed to disguise the commission of the very human rights violations that it purports to offer protection against.

If a government is at liberty to dispose of or otherwise make unavailable documents that bring into question its integrity, then are we living in a democracy? At this point it doesn’t matter if the information contained in the documents in question is correct or provable. The issue is the refusal of an elected government in Australia to hold itself accountable to the ‘rule of law’. While the underlying issue is systemic racial hatred and racial vilification within the Australian Public Service, the immediate issue for all Australians is the abuse of process that Mr. Stanhope’s refusal to disgorge these documents amounts to.

If the courts and the Ombudsman refuse to investigate flagrant violations of the ‘rule of law’ by an elected government because of the political implications associated with exposing high level corruption, in which direction are our basic human rights heading?

For the human rights revolution to be won, all Australians must demand the highest levels of accountability from our elected representatives and public servants.

Bakchos

[i] Ignatieff, M (2001) Human Rights As Politics and Idolatry, Princeton University Press.

Look you abo piece of shit. You were warned, you failed to listen, now we’ll see how tough you really are – you still have family in Canberra remember.

PTT these are nothing but vacuous words from a puerile mind.