How much can we ever know about the love and pain in another heart? How much can we hope to understand those who have suffered deeper anguish, greater deprivation, and more crushing disappointments than we ourselves have known?

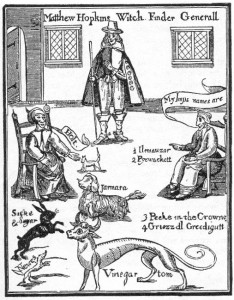

Orhan Pamuk, snow

Anna Elisabeth Schmieg of Hurden from the old County of Hohenlohe had a bad reputation with her fellow villagers. Anna’s reputation for drinking and brawling in taverns and for cursing her neighbours and family members was well known among officials, as were her husband’s shady business dealings as miller. Both Schmieg’s engaged in long-running feuds with neighbours and had had regular run-ins with the law in the decades before the witchcraft accusation. Furthermore, it was common knowledge within the village of Hurden that two of the Schmieg children had died in tragic circumstances and that there were serious conflicts within the family, particularly between Anna and her daughter, Eva, over issues of inheritance and Eva’s unsuitable marriage. Eva’s denunciation of her own mother as a witch was very important, if not decisive, in bringing about a conviction. More importantly for Anna Schmieg was that she was as seen as an “ungodly nuisance” by the local Lord, Prince Count Heinrich Friedrich of Langenburg, who was trying to instill religious, moral, and social discipline after the end of the long and ruinous Thirty Years’ War and Anna was seen as an obstacle to that aim.

On Shrove Tuesday, February 20, 1672, Anna Fessler, a young mother, died after eating a Shrovetide cake Anna Schmieg had her daughter deliver. Immediately, the villagers suspected that not only had Schmieg poisoned Anna Fessler, but that she was a witch. When the Langenburg Town Steward launched an investigation, Michel Fessler, Anna’s sisters, and her friends said their suspicions centered on Anna Schmieg.

True to the Teutonic zeal for exactness and following the guidelines set down in the criminal law code requiring a forensic medical investigation into suspicious deaths, the barber-surgeon hired to examine the body found no external clues as to the cause of death. A doctor of medicine then performed an autopsy on Anna Fessler. In the view of the doctor performing the autopsy, Fessler’s internal organs showed clear signs of poisoning, though importantly he would not conclude that the Shrove cake was the culprit.

There were any number equally plausible alternatives, the poison could have been introduced into the body from some external source — food, for example — or produced naturally within the body itself. It was possible that she might have died a sudden and tragic death but an altogether natural one. Poisoning, he concluded, was the likely cause of her death, but he refused to venture a guess about the source of poison.

The first mention of “witchcraft” came via a Lutheran pastor who had visited Anna Fessler before she died. He wrote to his superior that “the witch” had given Anna the poison in the little Shrove cake. Could the authorities use their powers to “eradicate the evil?”

The first mention of “witchcraft” came via a Lutheran pastor who had visited Anna Fessler before she died. He wrote to his superior that “the witch” had given Anna the poison in the little Shrove cake. Could the authorities use their powers to “eradicate the evil?”

Initially the authorities, including, Court Adviser Dr. Tobias Ulrich von Guelchen, chief counselor to Count Friedrich, viewed the case as a “suspected case of poisoning.” Von Guelchen decided that the most appropriate way forward was to consult with the medical faculty of a university to determine whether a crime had been committed. In the meantime, he had Anna Schmieg arrested.

Von Guelchen’s initial approach to the Hurden affair was an example of the “modern school of German jurisprudence” — clear lines of jurisdictional responsibility, high regard for procedural correctness, and careful attention to facts and details. But his other instinct was to leap ahead of the evidence and rely on his intuitions or beliefs.

As a devout and orthodox Lutheran, von Guelchen believed that moral and religious truths underpinned the law and completed it, providing those “quick flashes of truth” that evidence was slow to illuminate. For him, it was not a question of whether flashes of moral or religious insight would enter into his legal reasoning, but when, under what circumstances, and the weight he would give to them.

Von Guelchen relying on his own moral and religious prejudice came to the conclusion that Schmieg was both poisoner and a witch, but there was no material evidence to support these conclusions. The only sure evidence would be Anna’s confession, evidence he knew he would get only if she could be questioned under torture. To get permission, he took what evidence he had to legal scholars at the University at Altdorf (Nuremburg).

Legal experts at the University at Altdorf formed the view that the entire chain of events von Guelchen claimed to have reconstructed for the murder was built on “conjectures and presumptions that they found dubious and deficient.” They deemed his theory altogether “imperfect, insufficient, or even irrelevant.”

Dissatisfied with the response he received from Altdorf, von Guelchen went to Strasbourg for a second opinion. Strasbourg was an interesting choice for von Guelchen, as a professor of philosophy and ethics there had recently published a treatise marshaling all the compelling arguments against torture, arguing: that it stupefies the senses and makes it impossible to get at the truth; that it produces false confessions; that the Bible does not justify it; that torture produces tyranny and injustice; that nature itself abhors torture; and that especially in cases of occult crimes torture produces injustice.

The Strasburg jurists also harbored very grave doubts about the evidence. They admitted that, strictly following imperial criminal law and the common standards of evidence, they could not legally prove Anna Schmieg was a poisoner and/or a witch. They, too, would have recommended clearing Anna of the charges but for the graver crime that she was a “godless, barbaric and crazy old woman. Her behavior betrayed her not simply as an impious or immoral woman, but as a traitor against God and the state. Her life was an affront to the Ten Commandments.“

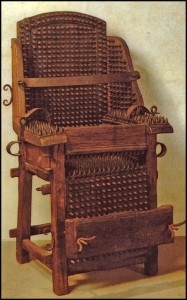

As weak as the evidence against Anna Schmieg was, von Guelchen was allowed to proceed with his examination of her under torture. Anna Schmieg was tortured several times until in the end she made a confession, but this was still not good enough for von Guelchen. On November 1, 1672 despairing of finding the right tactics to get Anna Schmieg to say the words required for a full and complete repentance, von Guelchen drew up a list of charges. All Anna Schmieg was required to do was affirm each one.

Finally after having endured as much pain as she could, Anna Schmieg affirmed the following confession several times, the last time on the morning of her public execution on November 8, 1672 in the small residence town of Langenburg:

- She was seduced in Regenbach as a maid of fifteen or sixteen years by the evil spirit and was persuaded to renounce God and her baptismal covenant, then with her blood and signature bound herself over [to the Devil] in a new baptism; after this [she] attended the witches’ dances and did a lot of evil to men and cattle, in particular:

- In Bachlingen she murdered her child and little boy of four years with a poisoned porridge.

- [She] gave her still living daughter a [witch’s] shot in the shoulder; which pained her for an entire year;

- [She] even wanted to murder this same [daughter] last Shrovetide Eve with a poisoned little cake and because

- She was prevented from doing so, commanded that it be brought to Anna Fessler, now deceased; from which she [Fessler] died within a few hours.

- [She] then sent a poisoned little cake to the little Fessler boy, which the father kept the child from eating, otherwise he too would have lost his life.

- Once again the daughter innocently brought another of these poisoned little cakes to the coachman’s wife in Hurden, whose dog refused to eat it, and it was thrown away;

- The [she] saved two other poisoned little cakes for [Michel] Fessler and her son-in-law; and because he did not come, threw them away in the ditch beside the mill.

- [She gave] a widow in Forst named Eva a [witch’s] shot in the arm which gave her unbearable pain.

The list goes on, and on, and on… what is interesting about Anna Schmieg’s confession was that it contains no outlandish claims about demonic possession or powers, it remained consistent with the laws of nature. In the period from 1560s through to the 1580s, critics of the witch trials considered confessions incredible because the stories clashed with authoritative accounts of nature and even the specific requirements of the law. For this reason the magistrates of Rothenburg ob der Tauber hesitated in 1587 to accept one boy’s fantastic stories about witchcraft. Concerns like this help explain why some court officials including von Guelchen tailored the confessions of witchcraft their courts produced to fit the more narrowly defined crime of sorcery and witchcraft according to article 109 of the Carolina. Desiring to widen the law, but also wanting to avoid the controversial aspects of the elaborated theory of witchcraft, the writers of the Saxon code of 1572 broadened the definition to include apostasy. They simply left aside other elements of the elaborated concept, including night flight, the witches’ Sabbath, and so on. Hence in those territories influenced by the Saxon ordinance, witch trials tendered to produce confessions which restricted the range of preternatural activity of witches and demons. If confessions were to be effective, if they were to bring an end successfully to a moral panic and a social crisis, they had to draw on those norms and values and narrative structures widely deployed in society.

The norms, values and narrative structures of society

In the final analysis, Anna Schmieg was condemned to torture and then executed as a confessed murderer and witch because she was in the eyes of her community a “godless, barbaric and crazy old woman. Her behavior betrayed her not simply as an impious or immoral woman, but as a traitor against God and the state. Her life was an affront to the Ten Commandments.” Hopefully not many people living in today’s the so called democratic West would consider these sufficient reason to deprive someone of not only their livelihood, but ultimately of their dignity and life. After all, torture is more about destroying a person’s dignity than it is about getting to the truth.

The problem with my hopeful affirmation about the West is that in Australia, which claims to be a democratic Western style state, the type of unlawful condemnation that Anna Schmieg was subjected to in an isolated German hamlet in the Seventeenth Century, continues to this very day.

While we may no longer hear the charge, witch, we hear on a regular basis the equally evocative charges of Muslim, refugee, Aborigine or god forbid simply that of free thinker. Last Sunday Sydney witnessed an outbreak of violence the likes of which we have not seen since the 2005 Cronulla riots. Were the people involved in this unrest simply protesting about a foreign film that portrayed the The Prophet Mohammad (Peace and Blessings be Upon him) in a scandalous way, or was the root cause of last weekend’s unrest more to do with the norms, values and narrative structures of contemporary Australian society?

If you take a few minutes to think about it and it really should only take you a few minutes, when was the last time you can recall the mainstream media presenting Muslims, refugees or Aborigines in a positive light? In writing this post, I applied my mind to the exact same question; I still haven’t managed to come up with an answer. The point is, our so called political leaders, see no issue in launching broadside after broadside against these classes of Australian citizens in order to achieve short term political objectives. Worse, our lacklustre and morally bankrupt media, more concerned about the bottom line and sensationalism than in reporting the truth, see no issue in reinforcing the negative stereotypes of certain classes of Australian citizens that our so called leaders create to further their political agendas.

The difference between what happened to, Anna Schmieg in an isolated Seventeenth Century German hamlet and what happens in contemporary Australia is that; at least the jurists and philosophers at the universities in Altdorf and Strasburg were prepared to voice their doubts about the legality if not the morality of what von Guelchen was doing in the name of his own prejudice. When was the last time any of you heard a leading Australian jurist or philosopher speak out against the ongoing negative stereotyping Muslims, refugees and Aborigines are subjected to in Australia on a daily basis?

Make no mistake; it is this continuing negative stereotyping of certain classes of citizens that create the narrative structures of our society. Are we as society prepared to continue moving in a direction that could one day see an innocent person condemned simply because they in the eyes of our community appear as “godless, barbaric and crazy” simply because they are a Muslim, a refugee or an Aborigine. Laugh if you will, but this is the way our society is heading unless as a community we make a stand and demand more from our so called leaders.

So we have all sold our souls to the Devil of the popular media and the government. I sense a theme developing here!

Things really have not changed much in 400 years have they

All i will say is that Australia is making a rod for its own back with its race relations issues.

On the Anna Schmieg issue, sounds to me like a pack of guys got together and decided to have a bit of fun with a helpless woman – sounds like the NSW Police really!

Rioys, official lies, fitting people up, manipulating the legal system to achieve personal and political ends. Sounds like the AFP in the Solomon Islands

Interesting post in light of Watershedd’s post today.

Its all about accountability within the process. Von Guelchen was apparently totally unaccountable as is the Inquisitor in relation to Pat’s issues.

Sinclair Peters it is about accountability within the process or in the case of the AFP and ACT Treasury, a total lack of accountability.

Seems like like state sancitioed S&M or B&D without consent. Again women have been victims of male sexual perversion.

You put it well sister melissa, you put it well

Girls you have an interesting way of looking at the world.

Pat was the victim of a witch hunt only in his case it was a boong hunt organised by the ACT Department of Treasury.

Totally agree with you on that point Tom Ashby

In the ACT witches have been replaced by Aborigines.

Yep Sue you got it, we blackfellas are Canberra’s witches of the 21st Century.

Richard Millhouse you put it well, blackfellas are Canberra’s witches of the 21st Century

What happened to Pat, a which hunt against the hated Aborigine, is this justice???

Aborigines, the new witches of Canberra.

Fuck Bakchos Glass, why don’t you just come out and say that Canberra is full of racist white cunts, instead of using all this window dressing crap. LOL Uncle Mick Glass !!!

Ah yes, the Aborigines are truly becomming the witches of Canberra.

Yes Sharon Coc Aborigines are the new witches of Canberra!

Poor bitch, sounds like sexual sadism to me. Typical white Christian male BS!

Yes David Harrison it does sound like white Christian male sexual sadism don’t it? Shit bet if the likes of the Inquisitor were alive then, well he would have been an Inquisitor for real!!!

Bill and David you have such a way with words, but I think you are both correct. As for OUR Inquisitor he is nothing more than a useless waste of space a blight on humanity.

Racism and the witch hunts like McCarthy and the Communists. It’s the same old bigatory just manafesting in differant ways.

As you have said before Bakchos Glass no amount of education will ever make us white!

More white Cgristian siko BS!