On Friday, The Australian Institute of Criminology (“AIC”) realest its Australian crime: Facts & figures: 2012 report, which provides sober reading for all those concerned about the on-going silent genocide of Indigenous Australia. Among other highlights, the report notes that there have been a further 325 indigenous deaths in custody since The Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody (“RCIADIC”) released its list of recommendations in 1991.

The #RCIADIC, which spent almost four years (1987-1991) and more than $40 million investigating 99 cases of Aboriginal deaths in custody, found there were ”too many Aboriginal people in custody too often”. The #AIC report echoed the royal commission’s view: ”At the heart of the problem is the over-representation of indigenous persons at every stage of the criminal justice system.”

The AIC report also shows that 97 per cent of juveniles in custody in the Northern Territory are Aborigines, a doubling of the 2007 figures. In Western Australia, Aborigines comprise more than two-thirds of juveniles in detention.

More importantly, two in every five deaths in juvenile justice custody since 1980 have been indigenous prisoners. Figures gathered by the University of Technology, Sydney, indicate young Aborigines are placed in detention at 31 times the rate of non-indigenous youth, which is an increase on the AIC figures shown in graph 2 below, which put the Indigenous juvenile incarceration rate at a mere 23 times the non-Indigenous juvenile incarceration rate. Whichever figures you choose to rely on, the incarceration rates for Indigenous juveniles are unacceptably high.

The facts

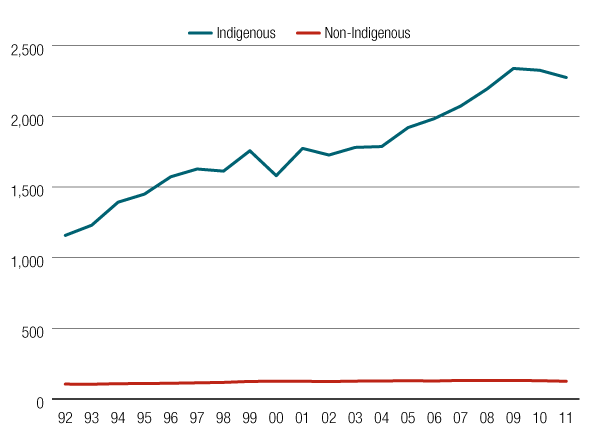

Graph 1: Adult Indigenous incarceration rates 1992-2011 (per 100,000 population)

- In 2011, 74 percent of prisoners were of non-Indigenous backgrounds.

- However, Indigenous offenders are imprisoned at a much higher rate than non-Indigenous offenders. This trend has been evident over the 20 year recording period. In 2011, the rate of imprisonment of Indigenous offenders was 18 times higher at 2,276 per 100,000 population than the rate of 125 per 100,000 for non-Indigenous offenders.

- In the past three years, both the Indigenous and non-Indigenous imprisonment rates have been in decline. Between 2009 and 2010, the rate of Indigenous offender imprisonment decreased by three percent, while the rate of imprisonment for non-Indigenous offenders decreased by four percent.

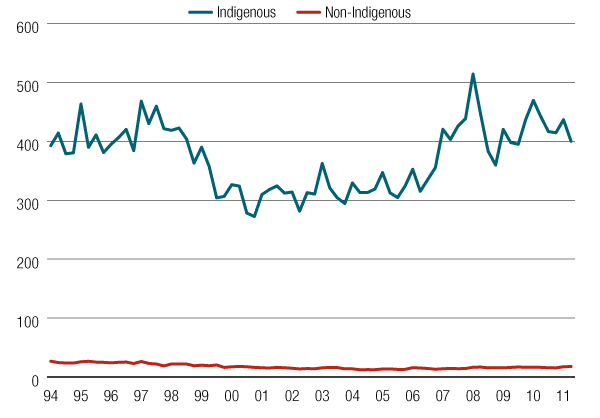

Graph 2: Juvenile Indigenous incarceration rates 31 March 1994 to 30 June 2011 (per 100,000 of that status per year)

- On 30 June 2011, 52 percent of the juvenile prison population were of Indigenous background.

- The rate of incarceration of Indigenous juveniles is currently five percent higher than that recorded in 1994. Between these two years however, the rate has fluctuated. Specifically, the rate was lowest in the year 2000 at 272 per 100,000 population and peaked in 2008 at 514.

- In 2011, the rate of incarceration of Indigenous juveniles was 400 per 100,000 population. Therefore, Indigenous juveniles were 23 times more likely to be incarcerated than non-Indigenous juveniles.

- Conversely, the rate of non-Indigenous juvenile incarceration has remained below 20 per 100,000 population for the last 12 years. In 2011, there were 383 non-Indigenous juveniles in prisons; a rate of 18 per 100,000 population non-Indigenous juveniles.

The Canadian experience

Australia is not the only country to be faced with the dilemma of Aboriginal over representation in the criminal justice and prison system. Canada has much the same problem and for many of the same reasons. The aboriginal people of Canada like the aboriginal people of Australia have been victims of ruthless exploitation at the hands of greedy, self-interested interlopers. Interestingly, the original source of the interlopers was the same, British and European expansion from the late fifteenth to the early twentieth centuries witnessed wave after wave of dispossessed Europeans leaving their homelands in search of other peoples land and resources. These dispossessed Europeans thought nothing of genocide as a means of clearing the way for their settlements and commercial operations. Aboriginal dispossession and disenfranchisement followed. The end result has been generation after generation of aboriginal people living in an oppressive environment of racism, violence, poverty and medical and educational neglect. The aforementioned statistics provide ample testimony to where this ultimately leads.

The Canadians ultiamtely adopted a legislative approach to the problem and in 1996 introduced Section 718.2(e) to the Criminal Code. Section 718.2(e) directs that “all available sanctions other than imprisonment that are reasonable in the circumstances should be considered for all offenders, with particular attention to the circumstances of aboriginal offenders” [underlining in the original]. One of the reasons for the introduction of Section 718.2(e) in 1996 was the sad reality that Aboriginal inmate’s makeup about 10% of the Canadian prison population, while accounting for only 2% of the greater population.

Gladue case

R v. Gladue [1 SCR 688] was the first Supreme Court of Canada case to consider the application Section 718.2(e). The Court concluded that Aboriginal offenders are as a result of unique systemic and background factors, more adversely affected by incarceration and less likely to be rehabilitated by it, because imprisonment is often culturally inappropriate and facilitates further discrimination towards them.

The Court further stated that the unbalanced ratio of imprisonment for Aboriginal offenders flows from a number of sources including “low incomes, high unemployment, lack of opportunities and options, lack or irrelevance of education, substance abuse, loneliness and community fragmentation.“ (para 67) It also arises from bias and discrimination against Aboriginal people within the justice system.

The circumstances of Aboriginal people differ from the broader population because many Aboriginal people are victims of systemic and direct discrimination, so many suffer the legacy of dislocation, and are affected by poor social and economic conditions

Ipeelee

In 2012 the Supreme Court of Canada had occasion to revisit R v. Gladue. On March 23, 2012 the court released joint reasons in the criminal sentencing appeals of two Aboriginal persons, Manasie Ipeelee and Frank Ralph Ladue (cited together as R. v. Ipeelee, 2012 SCC 13, [2012] 1 S.C.R. 433). This case is a positive decision for criminal law involving Aboriginal offenders.

As discussed above, Section 718.2(e) of the Canadian Criminal Code requires judges to take “the circumstances of aboriginal offences” into account in sentencing, especially to look at “all available sanctions other than imprisonment that are reasonable in the circumstances”. The Supreme Court laid out principles for this section in R. v. Gladue, [1999] 1 S.C.R. 688. Judges were directed to look at alternative sentencing options, and were directed to consider broad systemic and background factors that affect Aboriginal people generally and the offender in particular. Judges must take “judicial notice” of certain factors, and a case-specific report (a “Gladue Report”) must also be prepared.

In Ipeelee, the Supreme Court of Canada reaffirmed the importance of Gladue, and confirmed that it applies in all contexts, including when sentencing a long-term offender for breach of a Long-Term Supervision Order.

Notably, the Supreme Court identified two errors that courts have been making in cases since Gladue:

Error 1, paras. 81-83:

“[S]ome cases erroneously suggest that an offender must establish a causal link between background factors and the commission of the current offence before being entitled to have those matters considered by the sentencing judge”.

The Supreme Court held that such an approach “displays an inadequate understanding of the devastating intergenerational effects of the collective experiences of Aboriginal peoples. It also imposes an evidentiary burden on offenders that was not intended by Gladue.” The interconnections between background factors and the individual’s offence are “too complex” to draw the exact lines from A to B.

Error 2, paras. 84-87:

“perhaps [the] most significant issue”, is the “irregular and uncertain application of the Gladue principles to sentencing decisions for serious or violent offences”.

The Supreme Court emphasized that “sentencing judges have a duty to apply s. 718.2(e)”, in “every case involving an Aboriginal offender”; failure to do so is an error that should be corrected by an appeal judge.

In discussing this second error, the Supreme Court noted:

[86] In addition to being contrary to this Court’s direction in Gladue, a sentencing judge’s failure to apply s. 718.2(e) in the context of serious offences raises several questions. First, what offences are to be considered “serious” for this purpose? As Ms. Pelletier points out: “Statutorily speaking, there is no such thing as a ‘serious’ offence. The Code does not make a distinction between serious and non-serious crimes. There is also no legal test for determining what should be considered ‘serious’” (R. Pelletier, “The Nullification of Section 718.2(e): Aggravating Aboriginal Over-representation in Canadian Prisons” (2001), 39 Osgoode Hall L.J. 469, at p. 479). Trying to carve out an exception from Gladue for serious offences would inevitably lead to inconsistency in the jurisprudence due to “the relative ease with which a sentencing judge could deem any number of offences to be ‘serious’” (Pelletier, at p. 479). It would also deprive s. 718.2(e) of much of its remedial power, given its focus on reducing overreliance on incarceration. A second question arises: Who are courts sentencing if not the offender standing in front of them? If the offender is Aboriginal, then courts must consider all of the circumstances of that offender, including the unique circumstances described in Gladue. There is no sense comparing the sentence that a particular Aboriginal offender would receive to the sentence that some hypothetical non-Aboriginal offender would receive, because there is only one offender standing before the court.

[87] The sentencing judge has a statutory duty, imposed by s. 718.2(e) of the Criminal Code, to consider the unique circumstances of Aboriginal offenders. Failure to apply Gladue in any case involving an Aboriginal offender runs afoul of this statutory obligation. As these reasons have explained, such a failure would also result in a sentence that was not fit and was not consistent with the fundamental principle of proportionality. Therefore, application of the Gladue principles is required in every case involving an Aboriginal offender, including breach of an LTSO, and a failure to do so constitutes an error justifying appellate intervention.

Justice Rothstein, the lone dissenter in this case, provides a counterargument: the safety of the public is of paramount importance:

Once an Aboriginal individual is found to be a long?term offender, and the offender has breached one or more conditions of his or her LTSO, alternatives to a significant prison term will be limited. The alternatives to imprisonment must be viable and the sentencing judge must be satisfied that they are consistent with protection of society. Alternatives may include returning Aboriginal offenders to their communities. However, as in all cases, this must be done with protection of the public as the paramount concern; Aboriginal communities are not a separate category entitled to less protection because the offender is Aboriginal. Where the breach of an LTSO goes to the control of the Aboriginal offender in the community, rehabilitation and reintegration into society will have faltered, if not failed. In such case, the sentencing judge may have no alternative but to separate the Aboriginal long?term offender from society for a significant period of time. Nevertheless, during the period of incarceration, the Aboriginal status of the long?term offender should be taken into account for the purpose of providing appropriate programs that are intended to rehabilitate the offender so that upon release, the substantial risk of reoffending may be controlled.

As I have argued time and again on Blak and Black, it’s up to the politicians to make a stand on the issue of race and racism in Australia. The #AIC statistics demonstrate a situation that is at least as bad as it was in Canada before the introduction of Section 718.2(e) into the Canadian Criminal Code. But, as the Canadian experience has shown, legislation is not always enough. The courts also need to take responsibility for the way they treat Aboriginal defenders. While Aboriginality is not, and never can be an excuse for criminality, it is nevertheless the reason, and therefore a mitigating factor in, why so many of our sisters and brothers are finding themselves before the white man’s courts charged with crimes they have been driven to commit out of desperate circumstances. Desperate circumstances resulting from 225 years of exploitation, racism and cultural genocide.

If Canada has legislation, how do you think Ipeelee will play out in the Bugmy High Court appeal?

Bakchos I think what you say about the issue of race being something that needs to be addressed by the legislature rather than the courts has merit. However if the legislature won’t address the issue, then the only option the disenfranchised have, and lets face it, Aborigines are disenfranchised, is the courts.

Something has to be done about Aboriginal over representation in the prison system. The pigs are racist filth and the courts and the DPP are not much better. There needs to be justice and accountability on the issue of Aboriginal prison rates. Racism is absolutely part of the issue. You think Abbott will be ant better than Gillard on the issue? Think again!!!

Fuck the politicians, fuck the courts, it’s our land, time we demanded it back!!!!!!!!!!!!

Indeed Uncle Reg, it is our land, but to make any genuine progress we’re going to have to operate within the system that is available. Anything else will be counter productive at this stage. Its time we ALL worked as a unified group, not individually chasing our own personal agendas. We must learn from whitie in order to hold him accountable.

These statistics are appalling, Australia should be ashamed. I understand the issues are difficult, but the problem does not so much rest with the Indigenous people who are offending as it does with the system that has allowed this appalling situation to develop in the first place.

What I find interesting about this post is both the similarities and differences between Canada and Australia. Perhaps 200 years does make a difference! While the underlying issues of the plight of Aborigines in both countries remains the same, the Canadians have taken some positive stems to address the law and order issues. What is missing from the Canadian approach is any mention of addressing the underlying issues – poverty, disadvantage and racism.

The one big difference between Oz and Canada, is that the Canadians have passed legislation which gave the courts something to build on, this is yet to occur in Oz. Can the High Court follow a foreign decision that is based on legislation that Oz does not have? Where are our politicians prepared to make a stand for what is right over what is popular? Oh shit I for got, such a beast is yet to be found in Oz, silly me, I thought for a minute that we were living in a first world democracy, not some third world sham democracy that we actually find ourselves in. Bring on the revolution

Jail is a white concept and has no practical application to Aboriginal people. It’s time we all stood up to be counted for what is ours – always was, always will be, Aboriginal Land!

Yep sal I have to agree with you on that point – jail has no place in Aboriginal culture – whitie fuck off from our lands, NOW!!!

Aboriginal offenders have to be dealt with in some way. Habitual offenders become a burden on the communities they come from, those who don’t want jail, need to suggest other viable alternatives – so what are they?

Paul Oliver what do you suggest, just let the cunts in Canberra lock us all up without a fight, fuck that.

As a group Indigenous Australians are over represented in the criminal justice statistics, the sad reality is however, we as a group also commit a lot of crimes, many against our own people. Time for a little reflection before we jump on the blame wagon.

Richard Millhouse It sounds to me that you are the one speaking with a straight and powerful voice. The reality is, and it’s a sad reality, Mr Bugmy is a criminal and he must be treated as such or law and order become meaningless concepts.

Over represented in the criminal justice system – yes, unfairly so???

Tamara, perhaps there is some truth in your implied observation that Indigenous over-representation in the criminal justice system might be fair, but it is nonetheless a genuine concern that is in need of serious remedial action. To say Aborigines are criminals is to totally miss the point about the plight of Indigenous Australia. The answer is not easy, but ignorance is dangerous.

Perhaps if more people on both sides of the great white/black divide would embrace Sue Blacklock’s positive attitude, we could address the current issues with Aboriginal overrepresentation in the criminal justice system.

Address the problem at the root cause – Aboriginal disadvantage, and disenfranchisement. What follows might just be a positive for everyone!

I suspect that this post is part of a trio on Mr Bugmy and his upcoming High Court Challenge. The difference between Bugmy and Ipeelee is that Canada has legislation on the issue of Aboriginal sentencing that Australia does not. Both Bugmy and Ipeelee are violent Aboriginal criminals, however it is NOT the role of the courts to assume the place of the legislators – separation of powers, what ever happened to that concept?

Yes Bill you have identified the issue, Australia does not have the legislative framework that Canada does. The courts, even the High Court should not be trying to take on the role that’s reserved for the legislature.

If the legislature wont, or can’t act, then the courts have a role in addressing inequities in society, Mabo would never have happened if we waited for the legislature to act.

In the case of Mabo v. Queensland (No. 2) (1992) 175 C.L.R. 1, the High Court of Australia held that the common law of Australia recognised native title. The term ‘native title’ was used by the High Court to recognise that Aboriginal peoples and Torres Strait Islanders may have existing rights and interests in land and waters according to traditional laws and customs and that these rights are capable of recognition by the common law.

Specifically, the Court recognised a claim by Eddie Mabo and others on behalf of the Meriam people of the Island of Mer in the Murray Islands in the Torres Strait, that the Meriam people owned the land at common law because they were the traditional owners of their country under Islander law and custom.

The Queensland Government had earlier tried to extinguish the Meriam people’s property rights under the Queensland Coast Islands Declaratory Act 1985. However, the High Court ruled in 1988, in Mabo v. the State of Queensland (No. 1), that the Queensland law breached the Commonwealth’s Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (Cth).

The Mabo judgment dealt with some of the basic premises of the Australian legal system and society. In particular, the decision repudiated the notion of terra nullius – a land belonging to no one – on which the invaders’ whole land tenure system had been conveniently based. The High Court recognised that the rights of Aboriginal people and Torres Strait Islanders to native title may survive in certain areas and that their native title must be treated fairly before the law with other titles.

If the courts didn’t make a stand, there would be no Mabo and the Queensland Government would have achieved its racist objective. There is a role for the courts in social policy!

Yes the situation with Mabo is a point well made…