The ever-touring Englishman

“The ever-touring Englishman have built their bungalows

All over the sweet forrest

They drive their trains with smoke

O look at them, how they talk on their wires to one another

With their wires they have bound the whole world together for themselves.”

Original poem from Gondi oral tradition

To engage with dreams is to descend to the underworld, to let go of everything solid offered by “established” customs and habits, forms of perception and thought, and dive down into the primordial world – the hallucinatory world of feelings and images from which human culture emerged with difficulty. For humans, there are two types of primitive world: the one we experience as young children, before we are fully acculturated, and the one humanity as a whole must have lived through, so that each individual may pass through it again in a foreshortened version.

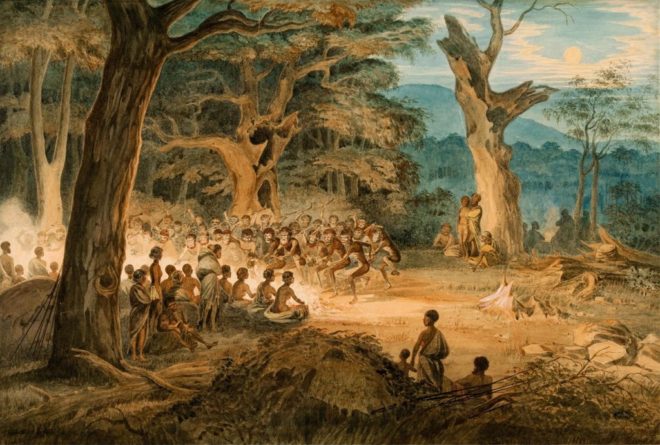

First Nations Australia pre 1788

When we dream, time loses all sense of proportion for us. One of the keys to understanding #FirstNations culture, is to recognise that First Nations Australians live on two inter-related planes – one physical the other metaphysical. So inter-related are these planes that they might be more exactly regarded as aspects of life. It is tempting to distinguish them as practical and symbolic respectively, but there is a sense in which both share elements of the other; they are not independent. The animals and plants are symbolic of the totemic bond between man and nature, between the present and the past; they are not only the source of sustenance, but the symbolic means by which man’s spirit moves on towards incarnation. Everything, including man, has its “shade” that remains when the shadow cast by sun or moon is no more. It is the inner shade, the soul, which leaves its mark on the land, the truest reflection more convincing than the corporeal substance that once left his legacy on a rock wall for others to find.

This universality of the shade implies the practical necessity of the symbolic and ritual approach to life. Unless the pre-existing souls became corporeal beings again, each in its own kind as animal, plant, man or landscape, there will be no physical existence. Hence, in order that all may live, First Nations Australians feel constrained, even while in the flesh, to cross into the spiritual plane. Nature herself presents the method for doing this. Just as the natural object, plant or body is the symbol and sacrament of the shade, so man’s approach must be in symbol. The rituals may be expressed in word, action, human decoration or art, engraved or painted objects. The rock faces of the escarpment record through the visual mediums of engraving and painting the sacred in First Nations society, through which the shade is re-born in outward form and remains present and potent as part of the eternal stream of the one life force and the Dreaming.

To fully appreciate these concepts its necessary to be present at a ceremony, to hear the songman chanting and tapping his sticks or boomerangs, setting the tempo and rhythm. Hear the didjeridoo or drone-pipe player in diapason tone giving depth and breadth to the rhythm, a base for the superstructure of song and stick-taps, of the accented exclamations, hisses, “breathings”, shouts and stamping of the dancers. See the drama, with stamping in time with the songman, arms and bodies expressing the theme of the chant in perfect time and representative movement. There indeed is the true chorus, bystanders included, clapping their hands or cupping their thighs to the beats. If it is not a men’s secret ceremony women may be seen on the edge of the dance-ground, bodies swaying, feet moving up and down, in and out, but always in the one place, their hands playing a string game, perhaps without string. All taking part are painted and adorned with patterns belonging to their various ceremonial groups symbolising their totems. Often the didjeridoo and tapping boomerangs may be painted. Secret rites also usually include painted or engraved symbolic objects of wood, stone or composite constitution which are used as a means of directing thoughts to the Dreamings, each pattern designed for a specific soul.

In the ritual dance we see the embodiment of the sacred art of First Nations Australia with its dance, singing and poetry as well as the visual arts of painting, engraving, molding, carving or sculpture. They are part of the symbolic Dreamtime, ensuring eternal life to nature and man. They are part of the mystic world, representing on the physical plane conceptions of this mystic world of shades and Dreamings, the virtue of which is expressed through symbol and sacrament.

Britain in the Nineteenth Century

“Where thou shalt hear the desperate lamentations,

Shalt see the ancient spirits disconsolate,

Who cry out each one for the second death;”

Divine Comedy – Inferno. Dante Alighieri (Translation, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow)

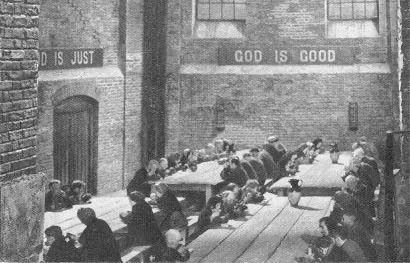

Charles Dickens revisited the workhouse debate in the 1850s, making several investigations into the conditions of the poor for his journal Household Words. What he witnessed confirmed to him the inadequacy of the workhouse system which at worse was perpetuating misery, poverty, starvation and ultimately death. In ‘a Walk in the Workhouse’, he described the scenes in a Marylebone workhouse:

“In a room opening from a squalid yard, where a number of listless women were lounging to and fro, trying to get warm in the ineffectual sunshine of the tardy May morning – in the “Itch Ward,” not to compromise the truth – a woman such as HOGARTH has often drawn, was hurriedly getting on her gown before a dusty fire. She was the nurse, or wardswoman, of that insalubrious department – herself a pauper – flabby, raw-boned, untidy…But, on being spoken about the patients whom she had in charge…sobbing most bitterly, wringing her hands…Oh, “the dropped child” was dead! Oh, the child that was found in the street, and she had brought up ever since, had died an hour ago, and see where the little creature lay, beneath this cloth! The dear, the pretty dear!”

Dickens likened another section of the workhouse to a prison, commenting that the meagre rations for inmates had created a primitive and bestial youth who had little to offer civilised society:

“In one place, the Newgate of the Workhouse, a company of boys and youths were locked up in a yard alone; their day-room being a kind of kennel where the casual poor used formerly to be littered down at night. Divers of them had been there some time. “Are they never going away?” was the natural inquiry. “Most of them are crippled, in some form or another,” said the Wardsman, “and not fit for anything.”

In Victorian society, the fear of poverty and destitution was an ever present threat for most working people. In Portsmouth, as in many other towns, those in need were a large element of the community. In Portsea alone, during the worst of the depression in 1818, some 955 men, women and children were in the Parish workhouse. Later, in 1834, it was calculated that in Old Portsmouth one person in eighteen was classed as a pauper by either receiving an allowance (out relief), or living in the workhouse. Similarly, in 1863, one in fourteen of the town’s population was classed a pauper.

The plight of the inmates depended on the regime running the workhouse. One visitor to the workhouse wrote to the Hampshire Chronicle in 1830:

“…My unfortunate friend, with tears in his eyes, related to me the cruelty of the new overseer…who has introduced such an economical plan as to not only deprive the poor people of the little comforts they had ever before enjoyed, but even of the necessities of life. I found that this reforming gentleman had taken 20lbs of meat per day from the poor people’s usual allowance, which was barely sufficient for sustenance; not content with this pinching their bellies, he has taken from the old men their tobacco, the only luxury they enjoyed; from the old women and children the trifling quantity of sugar which has ever been considered by all other overseers as necessary, and by no means an extravagance …”

Escape from the Inferno

“And thou shalt see those who contented are

Within the fire, because they hope to come,

Whene’er it may be, to the blessed people;”

Divine Comedy – Inferno. Dante Alighieri (Translation, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow)

“Our passage to Port Jackson’, took up but few hours… Having passed between the capes which form its entrance, we found ourselves in a port superior, in extent and excellency, to all we had seen before. We continued to run up the harbor about four miles, in a westerly direction, enjoying the luxuriant prospect of its shores, covered with trees to the water’s edge, among which many of the Indians [First Nations people] were frequently seen” Captain Watkin Tench – description of the arrival of the First Fleet into Sydney Harbour

One peoples utopia, another peoples genocide

“There sighs, complaints, and ululations loud

Resounded through the air without a star,

Whence I, at the beginning, wept thereat.

Languages diverse, horrible dialects,

Accents of anger, words of agony,

And voices high and hoarse, with sound of hands,

Made up a tumult that goes whirling on

For ever in that air for ever black,

Even as the sand doth, when the whirlwind breathes.

And I, who had my head with horror bound,

Said: “Master, what is this which now I hear?

What folk is this, which seems by pain so vanquished?”

Divine Comedy – Inferno. Dante Alighieri (Translation, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow)

The Aboriginal Mother

Oh! Hush thee – hush my baby,

I may not tend thee yet,

Our forest-home is distant far,

And midnight’s star is set.

Now, hush thee – or the pale faced men

Will hear thy piercing wail,

And what would then thy mother’s tears

Or feeble strength avail!

Oh, could’st thy little bosom,

That mother’s torture feel,

Or could’st thou know thy fathers lies

Struck down by English steel;

Thy tender form would wither,

Like the kniven in the sand,

And the spirit of my perished tribe

Would vanish from our land.

For thy young life, my precious,

I fly the field of blood,

Else had I, for my chieftan’s sake,

Defied them where they stood;

But basely bound my woman’s arm,

No weapon might it wield:

I could but cling round him I loved,

To make my heart a shield.

I saw my firstborn treasure

Lie headless at my feet,

The goro on his hapless breast,

In his life-stream is wet!

And thou! I snatched thee from their sword,

It harmless pass’d by thee!

But clave the binding cords – and gave,

Haply, the power to flee.

To flee! My babe – but wither!

Without my friend – my guide!

The blood that was our strength is shed!

He is not by my side!

Thy sire! Oh! Never, never

Shall Toon Bakra hear our cry:

My bold and stately mountain-bird!

I thought not he could die.

Now who will teach thee, dearest,

To poise the shield, and spear,

To wield the koopin, or to throw

The boommerring, void of fear;

To breast the river in its might;

The mountain tracks to tread?

The echoes of my homeless heart

Reply – the dead, the dead!.”

And ever must the murmur

Like an ocean torrent flow:

The parted voice comes never back,

To cheer our lonely woe:

Even in the region of our tribe,

Beside our summer streams,

‘Tis but a hollow symphony –

In the shadow-land of dreams.

Oh hush thee, dear – for weary

And faint I bear thee on –

His name is on thy gentle lips,

My child, my child, he’s gone!

Gone o’er the golden fields that lie

Beyond the rolling clouds,

To bring thy people’s, murder cry

Before the Christian’s God.

Yes! O’er the stars that guide us,

He brings my slaughter’d boy:

To shew their God how treacherously

The stranger men destroy;

To tell how hands in friendship pledged

Piled high the fatal pire;

To tell, to tell of the gloomy ridge!

And the stockmen’s human fire.

Eliza Hamilton Dunlop

First published in The Australian 13 December 1838

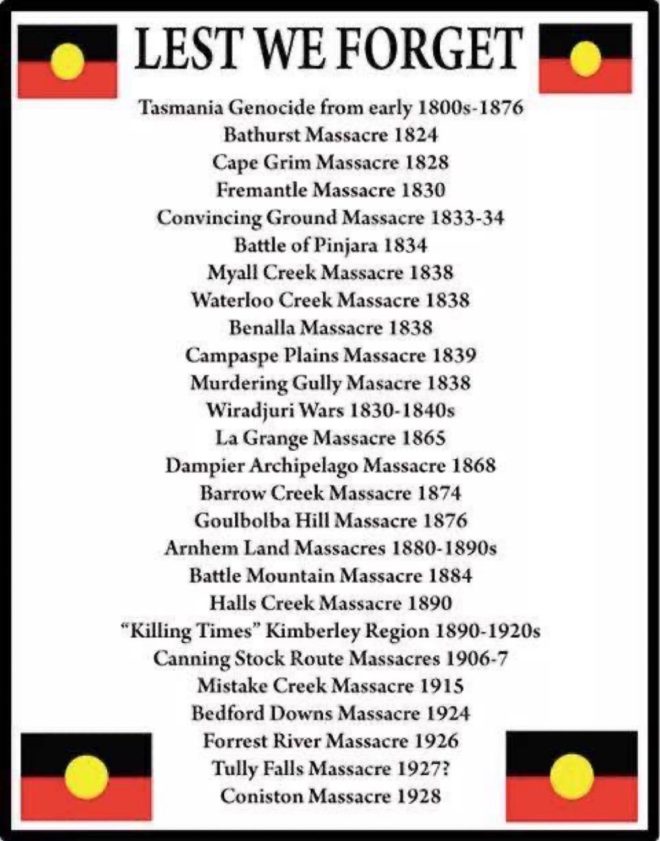

Eliza Hamilton Dunlop was a European migrant of Irish extraction who tried to give First Nations Australians a ‘voice’ during a time when we were all but silenced. ‘The Aboriginal Mother’ was written in response to the Myall Creek massacre, one of the many acts of genocide, committed against First Nations Australians, by the European invaders, in which some thirty unarmed First Nations men, women and children were shot and slashed to death by stockmen on a remote property in northern New South Wales in June 1838.The poem takes the form of an anguished address by the mother, supposedly the sole adult survivor of the killing, to her now fatherless child.

Genocide – really!?!

“Genocide brings to mind Hitler and the Jews, not Australia and Aborigines.”

Sarah Maddison, 2007

The word “genocide” originates from the work of Polish lawyer Raphäel Lemkin who developed the term in 1942 in response to the Nazi policies of systematic murder of Jewish people during the Holocaust, as well as in response to earlier precedents in history of targeting particular groups of people with the objective of their eradication. Following the work of Lemkin, the United Nations Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide in 1951 defined genocide as ANY of the following acts committed with intent to destroy, in whole or in part, a national, ethnical, racial or religious group, as such:

- Killing members of the group;

- Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group;

- Deliberately inflicting on the group conditions of life calculated to bring about its physical destruction in whole or in part;

- Imposing measures intended to prevent births within the group;

- Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group.

If you examine Australian history, you can see that the brutality of ongoing invasion and colonisation fits in this definition of genocide in several ways. Firstly, the killing members of the group, if you look at the work of Professor Lyndall Ryan and her research team has found that there were at least 270 frontier massacres over 140 years of Australian history, as part of a state-sanctioned and organised attempts to eradicate First Nations people. For Ryan’s work, a massacre is defined as the deliberate killing of six or more defenceless people in one operation. If you investigate some of these massacres in depth you can see how systematic they were. Ryan’s work is in no means comprehensive as many massacres were not documented and many others covered up. Because of colonial genocidal actions like state-sanctioned massacres, the First Nations population went from an estimated 1-1.5 million before invasion to less than 100,000 by the early 1900s.

Many will argue that state-sanctioned physical violence has not ended as many First Nations people still die at the hands of police or in police custody. This was highlighted by the 1991 Deaths in Custody report by the Office of the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Social Justice Commissioner for the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission. Today one First Nations person is killed in circumstances involving police every 28 days.

The different state governments of Australia also undertook genocide through their individual Aboriginal protection policies which involved Forcibly transferring children of the group to another group namely the removing First Nations children from their families and forcing them onto state-controlled reserves often run by religious missionaries to be eventually adopted by white families or taken by white families to work for them. The children subjugated by this genocide are commonly referred to as the “Stolen Generations”. This genocide was well documented in the 1997 Bringing Them Report by Human Rights and Equal Opportunity Commission.

It has been noted that the forcible removal of First Nations children has devastated the maintenance of First Nations culture as the intention of these reserves and the people who work for them was to “civilise” First Nations children, which meant prohibiting the children from using their language or partaking in their culture. Linguist Arthur Capell wrote in 1964: “Government policy looks forward to the loss of Aboriginal languages so that the Aborigines may be ‘assimilated’. Because of this, these protection policies were also undertaking what sociologist Christopher Powell refers to as slow genocide often called cultural genocide which is the destruction of language, culture, religion and social institutions of a group with the intended aim of annihilating the group (8). As a result of this, as of 2016, only 10 percent of the First Nations people spoke a First Nations language at home.

Due to these protection policies, many members of the Stolen Generations, their families and descendants suffer from trauma. Trauma has been shown to increase the risk of substance misuse, mental and physical ill-health, and can limit employment opportunities. As such, the different state governments protection policies could be argued to be Causing serious bodily or mental harm to members of the group which is another definition of genocide.

By 1969, all states had repealed the legislation allowing for the removal of First Nations children under the policy of ‘protection’. In 2008, during his time as Prime Minister, Kevin Rudd, apologised to the Stolen Generations on behalf of the Australian Parliament (11). However, it has been noted that the removal of First Nations by the state has not ceased. In fact, the number of First Nations children taken from their families has doubled since the 2008 apology as then were 17,664 First Nation children in out-of-home care in 2016-17.

The term genocide has been previously controversial when being applied to Australian History so why use the term genocide? We need to use the term genocide so we do not minimise the legacy of the colonisation and how the effects contemporarily manifest themselves. We need to use the term genocide to better understand our history so we can work to change the present and stop future genocide. We need to use the term genocide because it is the truth, it is what happened/is happening in Australia –

“Not everything that is faced can be changed, but nothing can be changed until it is faced.”

James Baldwin

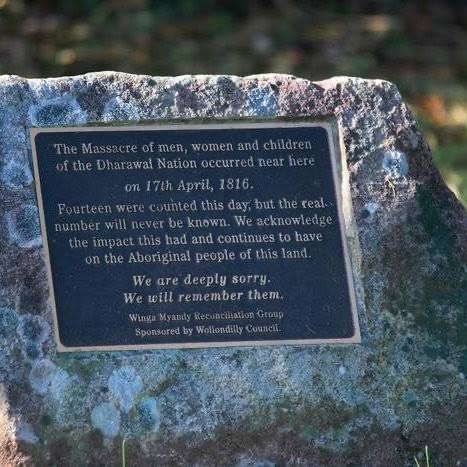

In Memory of the Appin Massacre

I stood and I watched as a mother cried,

when she had heard that her son had died.

He didn’t die because he was sick,

he didn’t die because of an accident

He died at the hands of an invaders malice.

I watched a father try to hold back tears,

His son had lived a scant few years.

Bakchos Glass (BlakandBlack.com)

The history of First Nations people in Australia over the last two hundred years since the arrival of Europeans is one of great suffering. Genocide, the introduction of European diseases, dispossession, subjugation and segregation reduced the First Nations population by 90% between 1788 and 1900

Today, First Nations Australians continue to face interpersonal and institutional racism which creates and sustains their lower socioeconomic status by excluding them from economic opportunities and land ownership. Moreover, First Nations men and women can expect to live 10.6 and 9.5?years less than non-Indigenous men and women respectively. A large and growing body of evidence consistently implicates racism as a key determinant of the health of Indigenous Australians.

However, one of the most persistent aspects of today’s discourse regarding racism in Australia is the very denial of its existence. A review of the linguistic and discursive patterns of contemporary speech in both informal and formal (parliamentary debates, political speeches, and the media) settings in Australia concluded that the social taboo against openly expressing racist beliefs has led to the development of strategies that present negative views of minority groups as reasonable and justified, while exonerating the speaker from charges of racism. This serves to constrain political efforts to address racism thus reinforcing racism.

Hypocrisy is your religion, and

Falsehood is your life, and

Nothingness is your ending; why,

Then, are you living? Is not

Death the sole comfort of the

Miserables?

Kahlil Gibran