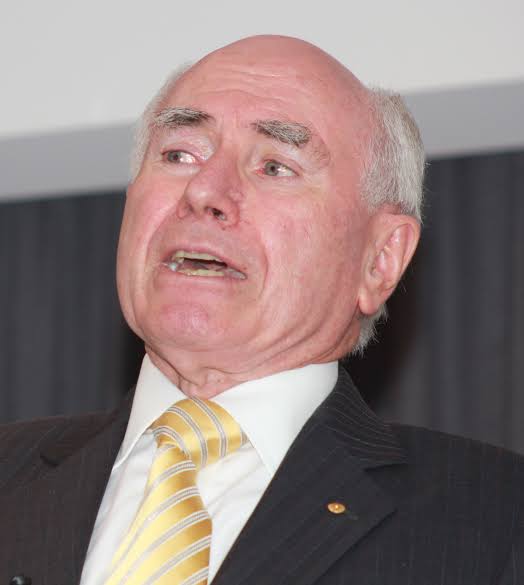

What did John Howard’s time as Prime Minister mean for #FirstNations Australia? On the 20th anniversary of his win, The Point takes a look at seven decisions that changed the landscape of First Nations affairs.

1. Introduced the #NorthernTerritoryIntervention

On June 21, 2007, John Howard launched an emergency intervention in the Northern Territory in response to the ‘Little Children Are Sacred’ report. The response was to ‘protect Aboriginal children from sexual abuse and family violence.’

Aboriginal people were not consulted throughout the process, and as a result their lives were heavily regulated.

The intervention gave the Government power to acquire Aboriginal land for five years, and quarantine half of all welfare payments for basic items.

“[He] just wanted to use Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory, and the vulnerability of Aboriginal people in the Northern Territory to position a [weak] Labor opposition, by portraying them as weak on child abuse, pedophilia, welfare abuse and so on – no evidence has come forward since to show that there’s any substance to what John Howard was trying to overcome.”

Michael Mansell, Australian lawyer and activist

2. Put an end to ATSIC

As soon as Howard entered parliament in 1996 he announced a major funding cut from the Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Commission (ATSIC), and appointed an administrator to take over the powers and functions of the board.

Six years later, he announced a review into #ATSIC which eventually resulted in the abolition of Australia’s only Indigenous self-governing body.

3. Swung the pendulum to make #NativeTitle laws tougher

Howard’s new government responded to the concerns of mining and pastoral groups by introducing his ‘Wik 10-Point-Plan’ to amend the Native Title Act(1993).

The changes to the Act under the proposed plan, further restricted the rights of First Nations people to negotiate, particularly on mining or pastoral leases.

Howard appeared on the ABC’s ‘7.30 Report’ in September of 1997, stating:

“What has happened with Native Title is that the pendulum has swung too far in one direction, particularly after the Wik decision. What I have done with this legislation is bring it back to the middle.”

And while pointing to a large map of Australia he said:

“The Labor Party and the Democrats are effectively saying that the Aboriginal people of Australia should have the potential right of veto over further development of 78 per cent of the landmass of Australia.”

4. Refused to apologise to the #StolenGeneration

Howard officially refused a national apology to members of the Stolen Generations, instead issuing a statement in Parliament stating:

“It’s sincere and deep regret.”

He again appeared on the ‘7.30 Report’ in 2000 saying:

“I speak for the entire government on this, and it’s a matter that’s been discussed at great length. We don’t think it’s appropriate for the current generation of Australians to apologise for the injustices committed by past generations.”

Eight years later Kevin Rudd, the then Prime Minister, made an official national apology to members of the Stolen Generation in Parliament on February 13, 2008. There was no compensation process.

5. Denied #genocide was ever committed against First Nations Australians

John Howard refused to accept the findings of the ‘Bringing Them Home report, which concluded that genocide had been exercised against Indigenous Australians as a result of children being forcibly removed.

He told Channel Seven’s ‘Sunday Night’ program:

“I didn’t accept the conclusion of the Bringing Them Home report that genocide had been practised against the Indigenous people.”

“I didn’t believe genocide had taken place, and I still don’t.”

Richard Weston, CEO of the Healing Foundation told The Guardian Australia:

“Whilst genocide may or may not have been the intent of the stolen generations’ policy, it is undeniable that the impact of forcibly removing children from their families, their country and their language was not designed to support the continuance of our 60,000-year-old culture.”

6. Voted against the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples

From the beginning of the Howard Government’s reign in 1996, Australia had disengaged with the #UnitedNations on a number of fronts.

In particular, Howard had successfully lobbied the Canadian government and Australian delegates, to oppose the UN’s Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples.

The UN Declaration reads:

“An important standard for the treatment of indigenous peoples that will undoubtedly be a significant tool towards eliminating human rights violations against the planet’s 370 million indigenous people and assisting them in combating discrimination and marginalisation.”

7. Derailed #Reconciliation

In 1997, John Howard overshadowed the Reconciliation Convention, a forum for Australians to discuss First Nations issues.

In his opening address, Howard said:

“In facing the realities of the past, we must not join those who would portray Australia’s history since 1788 as little more than a disgraceful record of imperialism such an approach will be repudiated by the overwhelming majority of Australians who are proud of what this country has achieved although inevitably acknowledging the blemishes in its past history.”

Howard’s description of the plight of First Nations Australians as a ‘blemish’ in history prompted many First Nations delegates in the audience to turn their backs in protest.

Three years later, Howard refused to take part in the Walk of Reconciliation, even though he promised to heal the rift between First Nations and non-First Nations Australians.

More than 200,000 people walked across Sydney’s Harbour Bridge during Reconciliation Week. The turn-out showed the huge support behind the reconciliation movement.

Instead he made plans for ‘a new Reconciliation’, ahead of the elections. He promised to hold a referendum to include a statement on reconciliation in the constitution.

Olga Havnen, Aboriginal advocate and activist, told ABC’s ‘Stateline’ in 2007 that:

“He was the PM who effectively derailed reconciliation for the greater part of his period in office. And yet when it seems to be in the dying days of … perhaps his term, I don’t know, but it just seems to be at the end of his term, and in the face of an election that now he wants to put on the agenda.”