As we delve into the complexities surrounding Australia’s gas landscape, it’s essential to recognise the paradox that the nation faces: despite being one of the world’s leading exporters of liquefied natural gas (LNG), Australia is grappling with warnings of domestic gas shortages, particularly in its southeastern states. Headlines often depict a grim picture of supply gaps, escalating prices, and potential disruptions to households and industries. Yet, the narrative of a “major gas shortage” is far from straightforward. Some experts argue that this crisis is more a product of policy choices, export priorities, and industry interests than an actual scarcity of gas.

This analysis aims to unpack the multifaceted reasons behind the gas shortage narrative in Australia, critically examining supply dynamics, export commitments, declining production, policy decisions, and the ongoing transition to renewable energy. By doing so, we can gain a clearer understanding of whether Australia truly faces a shortage or if the situation is a result of mismanagement of its abundant resources.

Australia’s Gas Abundance and Export Dominance

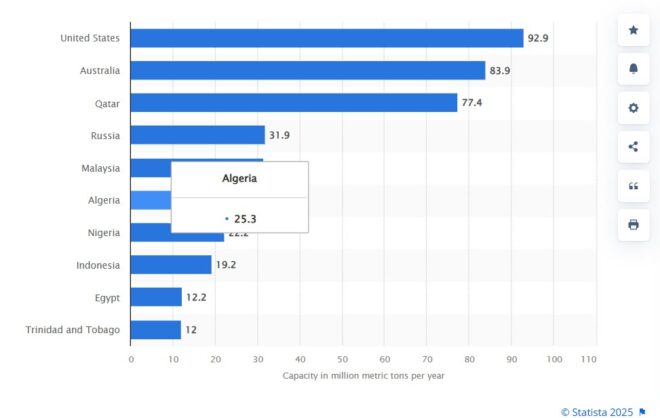

Australia stands as a giant in the global LNG market, ranking alongside Qatar and the United States as a top exporter. {PIC} In 2022 alone, the country exported around 82 million tonnes of LNG, primarily sourced from fields in Western Australia and Queensland. This staggering volume is estimated to be 35–36 times the amount required to address any potential shortfall in southeastern Australia, where the bulk of shortage warnings arise. Critics, including the Australia Institute, assert that the issue is not one of nationwide scarcity, but rather stems from the allocation of resources, with approximately 80% of production designated for export markets such as Japan, China, and South Korea.

The export boom took off in the mid-2010s, driven largely by the development of Queensland’s LNG facilities. Long-term contracts, often signed decades in advance, have committed vast quantities of gas to international buyers, thereby leaving domestic supply vulnerable to fluctuations in both production and demand. While Australia produces significantly more gas than it consumes domestically (about 1,500 petajoules annually), southeastern states like New South Wales, Victoria, South Australia, and Tasmania are increasingly confronted with warnings of deficits.

Declining Production in Traditional Gas Fields

One of the primary factors fueling the shortage narrative is the rapid decline of gas production in the Bass Strait, a historically crucial supply hub for southern Australia. Since the late 1960s, the Bass Strait fields, primarily operated by ExxonMobil and Woodside, have accounted for two-thirds of the gas consumed in Victoria and its neighbouring states. However, production has plummeted by 70% since 2010, with projections suggesting a drop from around 1,500 petajoules in 2022 to just 700 petajoules by 2028. The impending retirement of the Longford gas plant’s remaining facility in 2028 further exacerbates this decline.

Unfortunately, this depletion is not being offset by sufficient new local supply. Victoria, the largest gas-consuming state, has seen its total available supply forecasted to decrease from 297 petajoules in 2024 to 154 petajoules by 2028 – a staggering 48% reduction. Without new fields or infrastructure to transport gas from northern regions like Queensland, southern states are facing a structural supply challenge. The Australian Energy Market Operator (AEMO) has issued warnings of peak-day shortfalls beginning in 2025 and seasonal gaps starting in 2026, intensifying concerns about reliability.

Policy Choices and Domestic Reservation Gaps

Australia’s gas policy framework has come under scrutiny for favouring exports over domestic needs. Unlike Western Australia, which mandates a domestic gas reservation policy requiring producers to allocate 15% of output to the local market, the eastern states lack such a requirement. This absence can be traced back to historical decisions made during the Howard government in the early 2000s, which incentivised LNG export projects with minimal royalties and no robust domestic reserve mandates. Consequently, when global gas prices surged – partly due to the geopolitical tensions arising from the Russia-Ukraine conflict in 2022 – domestic prices mirrored these spikes, skyrocketing from $5 to over $18 per gigajoule.

Recent efforts to rectify this imbalance, such as the 2022 Heads of Agreement between the federal government and east coast LNG producers, aim to ensure that excess gas is offered to the domestic market first. However, these measures are voluntary and lack the enforcement mechanisms necessary to compel producers to prioritise local needs. The Australian Competition and Consumer Commission (ACCC) has noted that even with a forecast surplus of 69–110 petajoules in 2025, southern states could still face a 40-petajoule deficit in winter if uncontracted gas is exported rather than redirected for local consumption.

State-Level Restrictions and Investment Uncertainty

The landscape is further complicated by state-level policies. For instance, Victoria, which heavily relies on gas for heating and manufacturing, instituted a ban on onshore gas exploration and fracking in 2017, reflecting environmental concerns and public opposition. This decision has severely limited the development of new reserves to replace declining offshore production. New South Wales also has restrictive regulations in place, leaving Queensland as the primary growth area for east coast gas. However, transporting Queensland gas south requires substantial upgrades to existing pipeline infrastructure, which have not attracted sufficient investment due to high costs and uncertainties surrounding long-term demand.

Industry leaders and AEMO have repeatedly called for urgent investment in supply and infrastructure, but progress remains sluggish. The Port Kembla LNG import terminal in New South Wales, currently under construction, has the potential to alleviate some of the pressure, yet energy retailers are hesitant to commit to the project, citing a lack of immediate short-term shortages to justify the expenses involved. This investment paralysis heightens the risk of supply gaps, particularly during extreme weather events or peak demand periods.

The Energy Transition and Falling Demand

Adding another layer of complexity to the shortage debate is Australia’s ongoing shift toward renewable energy and electrification. As households and businesses increasingly transition to electricity – driven by high gas prices, milder winters, and state policies like Victoria’s ban on new residential gas connections starting in 2024 – gas demand is on the decline. The AEMO has reported that residential gas use could diminish by two-thirds by 2043, while gas-fired power generation has been trending downward since 2019. Notably, Victoria’s gas consumption reached a century-low of 177 petajoules in 2024.

This reduction in demand has delayed previously projected shortfalls – initially anticipated for 2023, now pushed to 2028 for peak days and 2029 for annual gaps. Advocates for renewable energy argue that this trend undermines the necessity for new gas projects, positing that electrification and efficiency measures could completely eliminate shortages. Nevertheless, gas still plays a critical role as a backup for intermittent renewable sources, particularly as coal plants like Eraring (extended to 2027) retire, creating uncertainty about future needs.

Industry Influence and the “Manufactured Crisis” Argument

Critics, including organisations like Greenpeace and the Australia Institute, argue that the shortage narrative is a strategic maneuver by the gas industry to legitimise new drilling initiatives. Projects such as Woodside’s Burrup Hub, which aims to export 85% of its output, exemplify the industry’s inclination towards profit over domestic security. The fact that LNG producers control 70% of known reserves in eastern and central Australia while paying minimal royalties or taxes (for instance, zero royalties on 56% of exports) only fuels accusations of exploitation. These groups contend that reallocating just a fraction of export gas – less than 3% of annual exports – could effectively close any southeastern gap without necessitating new drilling operations.

Critical Analysis: Shortage or Mismanagement?

The evidence suggests that Australia does not face an absolute gas shortage but rather a regional and policy-driven imbalance. Nationally, supply exceeds demand; however, southeastern states are suffering from declining local production and inadequate access to northern reserves. The export-heavy model, coupled with a lack of domestic reservation, exposes Australians to global price volatility and supply risks. While industry warnings of blackouts and price spikes are not without merit, they often overlook the potential for demand-side solutions or modest adjustments to export commitments. Moreover, the transition to renewables raises critical questions about the long-term relevance of gas, challenging the urgency surrounding new supply investments.

Conclusion

As of March 29, 2025, Australia’s so-called “major gas shortage” is a multifaceted issue rooted in historical export commitments, declining production from the Bass Strait, policy inertia, and an uneven transition to renewable energy. While the southeastern states face genuine supply risks, the national abundance of gas suggests that strategic reallocation, infrastructure investment, and demand reduction could alleviate the problem without necessitating an expansion of extraction efforts. The crisis appears less about a lack of gas and more about how it is managed – a challenge that demands balanced policymaking to prioritise domestic needs while navigating a de-carbonising future.

This nuanced perspective on Australia’s gas landscape underscores the importance of informed discourse and thoughtful policy decisions as the nation strives to balance its role as a global energy supplier with the needs of its citizens.