In the landscape of literary thought, few essays provoke as much contemplation and discussion as Oscar Wilde’s “The Decay of Lying,” published in 1891. This work stands as a remarkable paradox, intricately weaving a playful, yet profound defence of art’s autonomy, while simultaneously challenging the very fabric of how we perceive reality. Through the engaging dialogue between the characters Vivian and Cyril, Wilde asserts a revolutionary perspective: art does not merely serve as a reflection of nature or reality; rather, it possesses the extraordinary capacity to shape our perceptions and interpretations of them.

At the heart of Wilde’s argument lies a radical inversion of the traditional view of art as a mere imitation of life. He contends that the essence of art transcends the boundaries of mere representation, inviting us to reconsider the utilitarian approach that insists art must serve moral or factual purposes. In an age that often prioritises truthfulness and utility, Wilde’s assertion that art’s true value resides in its beauty and imaginative freedom stands as a bold declaration of aestheticism. This philosophy champions the notion that the worth of art is not diminished by its detachment from factual accuracy; instead, it flourishes in the realm of imagination, where the potential for creativity knows no bounds.

Wilde’s signature wit permeates the essay, transforming complex philosophical ideas into accessible and engaging discourse. His characters, through their spirited exchange, illuminate the notion that art’s primary function is not to provide an accurate portrayal of reality but to evoke emotion, provoke thought, and inspire the viewer’s imagination. In this light, the act of creation becomes an act of rebellion against the constraints of the mundane and the ordinary. Wilde encourages us to embrace the freedom that art offers, to revel in its ability to craft new realities that are as valid as the world we inhabit.

However, beneath the whimsical surface of Wilde’s essay lies a prescient insight that resonates with contemporary concerns. In our current era, where the proliferation of “alternative facts” and distorted narratives threatens the very fabric of societal cohesion, Wilde’s reflections on the nature of truth and deception take on renewed significance. When art – or its modern analogs – creates new realities, it risks fracturing the shared truths that bind societies together. The proverb, “even the devils in hell don’t lie to each other,” serves as a poignant reminder that no society can function effectively if deception becomes the norm. The delicate balance between imagination and truth becomes a critical concern, as the boundaries between art, reality, and fabrication blur in a world increasingly dominated by subjective interpretations.

Art as a Lens, Not a Mirror

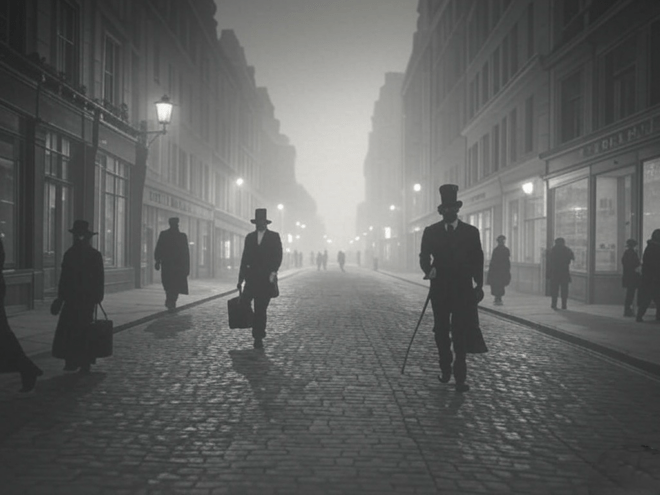

Wilde boldly asserts that life imitates art far more than art imitates life, a notion that invites us to reconsider the very nature of our experiences and the world around us. Through the lens of this thesis, Wilde offers a striking example: the fogs of London.

Vivian argues that these atmospheric conditions existed long before the advent of Impressionist painters. However, it was only after artists such as Claude Monet and James Whistler depicted the fog in their evocative, hazy brushstrokes that society began to notice and romanticise this quintessential aspect of the London landscape. As Vivian provocatively states, “Nature is no great mother who has borne us; she is our creation.” This assertion does not deny the existence of nature but rather posits that our experience of it is profoundly influenced by the transformative lens of art.

The implication of Wilde’s argument is both playful and radical. By subverting the realist tradition, which has long held that art should serve as a faithful reflection of the world, Wilde repositions the artist as a creator of perception rather than merely a recorder of reality. In his view, the purpose of art transcends documentation or moralisation; it is to invent, to offer beauty and imagination as ends in themselves. This perspective encapsulates the essence of Wilde’s aestheticism: art exists for its own sake, liberated from the constraints of utility or truth.

Wilde’s delight in this inversion carries an edge of irony that merits further contemplation. If art possesses the power to dictate how we perceive reality, what are the implications when that power is wielded not for the purpose of beauty but for manipulation? This question raises significant concerns about the ethical responsibilities of the artist and the potential for art to distort rather than illuminate our understanding of the world.

In an age where visual culture pervades our daily lives, Wilde’s insights resonate with renewed relevance. The pervasive influence of media, advertising, and social platforms can often skew our perceptions, leading us to construct realities based on curated images and narratives. The fogs of London, once a natural phenomenon, have been transformed into a romantic symbol through the artistry of Impressionists, and today, our collective consciousness is similarly shaped by the artistic choices made in various forms of media.

As we navigate this complex landscape, Wilde’s thesis challenges us to remain vigilant and discerning consumers of art and media. It prompts us to ask critical questions about the nature of our experiences and the ways in which they are filtered through artistic expression. Are we, like the inhabitants of Victorian London, at risk of overlooking the beauty of the mundane unless it is rendered through the lens of artistic interpretation? Or, conversely, are we susceptible to a reality crafted by the hands of those who seek to manipulate perception for ulterior motives?

Alternative Facts and the Erosion of Shared Truth

Wilde’s celebration of art’s creative license finds a dark echo in the modern phenomenon of “alternative facts.” Coined in 2017 by Kellyanne Conway to defend exaggerated claims about crowd sizes, the phrase has since become shorthand for narratives that defy evidence in favor of preference or agenda. If Wilde’s artists shaped perception through beauty, purveyors of alternative facts do so through distortion, crafting realities that serve political or ideological ends. Where Wilde saw art’s fictions as a source of delight, alternative facts often sow discord, undermining confidence in institutions and fracturing social cohesion.

Consider Wilde’s fogs in this light. The Impressionists gave us a new way to see London’s mists, but their paintings did not deny the fog’s existence – they heightened its presence through subjective interpretation. Alternative facts, by contrast, might insist the fog never existed or that it was something else entirely, regardless of what eyes and instruments report. This is not art shaping life but fabrication supplanting it. Wilde’s essay, for all its levity, hints at this danger: when perception becomes untethered from any anchor in reality, the result is not just aesthetic freedom but potential chaos.

The stakes here are societal. Shared truths – agreements on basic facts, even if interpreted differently – are a bedrock of collective life. As the proverb suggests, even a society of devils requires honesty to function; lies unravel the trust that holds any group together. Alternative facts, by presenting themselves as legitimate rivals to evidence, erode this foundation. They are not Wilde’s “beautiful untrue things” meant to enchant, but tools that widen fissures in a world already strained by division.

Aestheticism’s Double-Edged Sword

Wilde laments what he perceives as the “decay” of lying – the waning of imaginative exploration in a society increasingly fixated on realism and didacticism. In his view, the essence of art lies not in its fidelity to reality, but in its capacity to enchant and provoke thought. As his character Vivian states, “The aim of the liar is simply to charm, to delight, to give pleasure.” This assertion underscores a profound distinction: the lies of art are not designed to manipulate or wield power, as we often see in contemporary discourse surrounding “alternative facts.” Instead, they seek to elevate the human experience, offering a form of beauty that transcends the mundane.

However, Wilde’s argument raises a critical question: if the fabrications of art possess the power to reshape our understanding of reality, what boundaries must we impose on their influence? Wilde’s aestheticism operates under the assumption of benign intent – an inherent goodness in the transformative power of art. Yet, the principle that perception can be moulded, while captivating, does not guarantee positive outcomes.

In a contemporary context, Wilde’s insights seem to foreshadow our current predicament. He celebrates the artist’s ability to transcend the constraints of nature, yet he does not fully confront the implications of such power when it escapes the confines of the canvas and permeates the public sphere. The Impressionists, with their ethereal representations of light and atmosphere, enriched our vision, inviting us to see the world through a different lens. In stark contrast, the alternative facts that dominate today’s discourse serve to obscure rather than illuminate, clouding our collective understanding and fostering division.

Wilde’s essay, penned during a time of relative cultural stability, could afford a certain playfulness in its exploration of art’s role in society. Today, however, amidst a cacophony of misinformation and polarised narratives, his ideas take on a sharper, more urgent edge. The artistic endeavour, while capable of shaping life and perception, also bears the weighty responsibility of safeguarding shared truths. When “alternative” realities proliferate unchecked, they threaten to dismantle the very foundations of understanding that art, at its best, seeks to illuminate.

Conclusion: Beauty, Truth, and the Ties That Bind

“The Decay of Lying” is a love letter to art’s independence, a manifesto for beauty over utility. Wilde’s claim that art shapes how we see the world remains as compelling as it is mischievous, proven by his example of London’s fogs and the Impressionists who framed them. Yet, in defending the lie as an artistic virtue, Wilde unwittingly opens a door to its misuse. Alternative facts, though distant from his aesthetic ideal, exploit the same mechanism: the power to craft perception. Where Wilde sought to enchant, they aim to divide.

The essay’s brilliance lies in its provocation, urging us to question what we demand of art and reality. But it also serves as a cautionary tale. A society thrives on shared truths, however imperfectly grasped. When art – or its bastard offspring, alternative narratives – splinters those truths beyond repair, the result is not Wilde’s paradise of beauty but a cacophony of competing fictions. Even the devils, it seems, knew better than to let lies run unchecked.

In our quest for beauty and truth, let us remain vigilant, discerning the fine line between art that enchants and narratives that deceive, ensuring that the ties that bind our society remain strong amidst the complexities of perception and reality.