Democracy is a system of governance that derives its legitimacy from the consent of the governed. It thrives on the participation, accountability, and trust of its citizens. Among the myriad principles that contribute to the vitality of democratic societies, two stand out as foundational: freedom of speech and the rule of law. These twin pillars not only protect the democratic process but also ensure its adaptability and resilience in the face of challenges.

Freedom of Speech: The Voice of Democracy

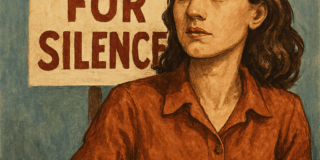

Freedom of speech is often heralded as the lifeblood of democracy. It is the mechanism through which individuals articulate their beliefs, challenge authority, and engage in the marketplace of ideas. Without the ability to speak freely, citizens cannot meaningfully participate in the democratic process, whether through voting, protest, or public discourse. This principle asserts that every person has the right to express their thoughts without fear of censorship or retribution, provided such expression does not directly incite violence or harm.

Historically, the concept of free speech has evolved over centuries. Its roots can be traced to ancient Athens, where citizens participated in open debate in the Ecclesia, though this privilege was limited to a small class of free men. The modern understanding of free speech emerged more prominently during the Enlightenment, with thinkers like John Locke and John Stuart Mill championing the idea that liberty of expression was essential to the pursuit of truth and the advancement of society. Mill, in his seminal work On Liberty (1859), argued that silencing an opinion – even a false one – deprives humanity of the opportunity to refine its understanding through debate. This perspective has since become a cornerstone of democratic theory.

In practice, freedom of speech serves multiple functions in a democracy. It acts as a safety valve, allowing dissent to be voiced rather than suppressed, thus preventing unrest from festering into rebellion. It fosters accountability by enabling citizens to criticise their leaders and institutions. The press, often called the “fourth estate,” relies on this freedom to investigate and report on matters of public interest, ensuring transparency. Moreover, free speech nurtures diversity of thought, which is vital in a pluralistic society where consensus must often be forged from competing viewpoints.

Yet, freedom of speech is not absolute. Most democracies impose limits to prevent harm – such as laws against defamation, incitement to violence, or hate speech – illustrating the delicate balance between individual liberty and collective well-being. The challenge lies in defining these boundaries without undermining the principle itself. In the United States, for example, the First Amendment guarantees broad protections, with the Supreme Court consistently ruling that even offensive or controversial speech deserves safeguarding. In contrast, European democracies often adopt a more restrictive approach, prioritising social harmony alongside individual rights. Regardless of these variations, the centrality of free speech to democratic participation remains undisputed.

The Rule of Law: The Framework of Justice

If freedom of speech is the voice of democracy, the rule of law is its backbone. At its essence, the rule of law holds that all individuals and institutions are subject to and accountable under a transparent, impartial, and consistently applied legal framework. This sanctity stems from the principle that no one – not even the most powerful – is above the law, a concept crystallised in the Magna Carta of 1215. This historic document established that royal authority was not absolute but constrained by legal norms, laying the groundwork for constitutional governance.

The rule of law encompasses several key elements: laws must be clear, publicised, and stable; they must apply equally to all; and they must be adjudicated by an independent judiciary. A.V. Dicey, a 19th-century British jurist, famously outlined three tenets of the rule of law: no one can be punished except for a breach of law established in the ordinary legal manner; no one is above the law; and the rights of individuals are secured by judicial decisions rather than arbitrary decree. These principles ensure that power is exercised predictably and justly, fostering trust in the system.

Historically, the rule of law has been a bulwark against tyranny. In medieval Europe, monarchs often ruled by divine right, their whims unchecked by legal accountability. The Magna Carta marked a turning point, followed centuries later by milestones like the English Bill of Rights (1689) and the U.S. Constitution (1787), which entrenched legal supremacy over executive power. In modern times, the rule of law has been tested by authoritarian regimes that manipulate or bypass legal systems to consolidate control. Democracies, by contrast, rely on it to maintain stability and legitimacy, ensuring that elections, property rights, and civil liberties are protected by enforceable standards rather than the caprice of leaders.

The rule of law also intersects with democracy through its role in safeguarding rights. Independent courts interpret and uphold constitutional guarantees, including freedom of speech, against encroachments by the state or private actors. Landmark rulings like Brown v. Board of Education (1954) in the United States demonstrate how the judiciary can enforce equality under the law, advancing democratic ideals. Conversely, when the rule of law erodes – through corruption, politicised courts, or selective enforcement – democracy falters, as citizens lose faith in the system’s ability to deliver justice.

The Symbiosis of Freedom of Speech and the Rule of Law

While freedom of speech and the rule of law are distinct principles, they are deeply interdependent. Free speech depends on the rule of law to protect it from arbitrary suppression. Without a legal framework that guarantees this right, governments or powerful entities could silence dissent with impunity. Consider authoritarian states where critics are jailed without due process; here, the absence of the rule of law renders free speech a hollow promise. Conversely, the rule of law relies on free speech to remain accountable and responsive. Public discourse exposes flaws in legal systems – whether through protests against unjust laws or media investigations into judicial misconduct – prompting reform and reinforcing the law’s legitimacy.

This interplay is evident in historical struggles for democratic rights. The civil rights movement in the United States exemplifies how free speech, exercised through marches and speeches, pressured the legal system to uphold equality under the law. Figures like Martin Luther King Jr. leveraged both principles: their words challenged societal norms, while their appeals to the Constitution and courts secured lasting change. Similarly, the abolition of apartheid in South Africa required both vocal activism and the establishment of a legal order that dismantled discriminatory statutes.

However, tensions can arise between the two. Free speech can sometimes strain the rule of law, as when inflammatory rhetoric undermines public order or judicial authority. The January 6, 2021, attack on the U.S. Capitol, incited in part by provocative statements, illustrates how unchecked expression can threaten legal stability. Conversely, overly rigid enforcement of laws can stifle speech, as seen in debates over censorship during wartime or emergencies. Striking a balance requires constant vigilance, ensuring neither principle overshadows the other.

Threats and Challenges in the Modern Era

In the 21st century, both freedom of speech and the rule of law face new challenges. The digital age has amplified free speech through platforms like social media, enabling unprecedented access to information and expression. Yet, it has also unleashed misinformation, hate speech, and polarisation, prompting calls for regulation that risk overreach. Governments and corporations alike grapple with how to moderate online content without infringing on democratic freedoms, a dilemma that tests the adaptability of legal systems.

Simultaneously, the rule of law is under strain from populism, corruption, and assaults on judicial independence. Leaders in some democracies have sought to undermine courts or manipulate laws for political gain, eroding the impartiality that sustains public trust. Global crises, such as pandemics or climate change, further complicate the picture, as emergency measures sometimes curtail rights in the name of security. These dynamics highlight the fragility of democracy’s foundations and the need to reinforce them through civic engagement and institutional resilience.

The Zionist Threat to the Rule of Law and Freedom of Speech in Australia

In recent years, a growing chorus of voices in Australia has expressed alarm over what they perceive as a Zionist threat to the foundational democratic principles of the rule of law and freedom of speech. This concern stems from allegations that Zionist organisations, notably the Zionist Federation of Australia (ZFA) and affiliated groups, exert undue influence on legal and political systems to suppress dissent, particularly criticism of Israel’s policies. Critics argue that such actions undermine the impartiality of the law and the right to free expression, posing a direct challenge to Australia’s democratic framework. While these claims are contentious and fiercely debated, they warrant examination in the context of how the rule of law and free speech – democracy’s twin pillars – interact with organised advocacy in a pluralistic society.

Alleged Influence on the Rule of Law

The rule of law, defined here as the principle that all individuals and institutions are accountable to transparent and impartially applied laws, is seen by some as under threat from Zionist lobbying efforts. Critics point to specific legislative and judicial developments as evidence. For instance, the adoption of the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) working definition of antisemitism by the Australian government in 2021, and its subsequent endorsement by universities in 2025, has been contentious. The IHRA definition includes examples that equate certain criticisms of Israel – such as denying the Jewish people’s right to self-determination or applying double standards – with antisemitism. Opponents, including the Jewish Council of Australia and Palestinian advocates, argue that this conflation risks criminalising legitimate political speech, thereby skewing the legal system to favor one perspective. They contend that it empowers authorities to selectively prosecute or intimidate individuals, as seen in the 2025 case of Hash Tayeh, a Melbourne activist charged with “using insulting words in public” for declaring “all Zionists are terrorists” at a protest. Legal experts have noted that such charges, rarely applied to political statements, suggest a politicised application of the law, potentially eroding its impartiality.

Further, the passage of the Criminal Code Amendment (Hate Crimes) Bill 2025, which introduced mandatory minimum sentences for terrorism-related offenses and hate symbol displays, has fueled debate. While framed as a response to rising antisemitism, critics like the Law Council of Australia warn that these laws could “risk serious injustice” by limiting judicial discretion and disproportionately targeting marginalised groups, including those critical of Israel. The concern is that Zionist advocacy – evidenced by public support from groups like the ZFA and the Executive Council of Australian Jewry – has pushed for legal measures that prioritise security over equity, challenging the rule of law’s commitment to fairness and proportionality.

Curtailment of Freedom of Speech

Freedom of speech, the right to express ideas without fear of censorship or retribution, is equally implicated in this discourse. Activists and progressive Jewish groups assert that Zionist influence has fostered a chilling effect on public discourse, particularly regarding Israel’s actions in Gaza and the occupied territories. The doxxing of pro-Palestinian voices, such as the 2023 leak of a WhatsApp group chat involving 600 influential Jewish creatives allegedly coordinating to limit employment opportunities for critics of Israel, is cited as an example of extralegal pressure. While the leakers framed it as an act of pro-Palestinian activism, the incident sparked fears of retribution among academics, journalists, and healthcare workers who oppose Israeli policies, suggesting that free expression is being stifled outside formal legal channels.

Legislatively, the failed Combating Misinformation and Disinformation Bill and the successful hate crime laws have heightened these concerns. The former, though abandoned, aimed to regulate online content, raising fears among free speech advocates that it could target criticism of Israel under the guise of combating hate. The latter, with its broad definitions of “harmful hate speech,” has been criticised by groups like Equality Australia for not distinguishing between incitement to violence and robust political critique, potentially ensnaring anti-Zionist voices. Posts on X and statements from figures like Mary Kostakidis and Adam Houda reflect a sentiment that the Australian Zionist Federation is “weaponising” laws to silence opposition to Israel’s actions, particularly its military operations in Gaza, which some label as genocidal.

Moreover, the treatment of pro-Palestinian protests – such as the arrest of a man carrying an Israeli flag “for his safety” during a 2023 Sydney rally, while anti-Jewish chants went largely unchecked – has led to accusations of selective enforcement. Zionist leaders like Jeremy Leibler of the ZFA questioned why such events were permitted, yet critics counter that this reflects a double standard where pro-Israel speech is implicitly protected, while pro-Palestinian expression faces scrutiny or suppression. This perceived asymmetry fuels the narrative that freedom of speech is being curtailed to align with Zionist interests.

The Counterargument and Democratic Tension

Defenders of Zionist advocacy, including Jewish community leaders, argue that these measures protect a vulnerable minority against a documented rise in antisemitism, particularly since the October 7, 2023, Hamas attacks. They assert that the rule of law is strengthened, not undermined, by laws targeting hate speech and terror symbols, and that freedom of speech does not extend to incitement or vilification. The ZFA and others maintain that criticising Israel is permissible, but targeting “Zionists” as a proxy for Jews crosses into antisemitism, a view supported by polls showing 77% of Australian Jews identify as Zionist. They reject claims of undue influence, emphasising their right to lobby within a democratic system, just as other groups do.

This debate reveals a deeper tension within democracy: the balance between protecting rights and preventing harm. Critics of Zionist influence see a threat to the rule of law and free speech in what they describe as a coordinated effort to reshape legal and social norms. Supporters see a necessary defense of a community under siege. The challenge for Australia lies in ensuring that neither perspective distorts the impartial application of law nor silences legitimate discourse, preserving the democratic ideals both sides claim to uphold.

Conclusion: Safeguarding Democracy’s Core

Freedom of speech and the rule of law are not merely abstract ideals; they are the practical mechanisms that enable democracy to function and endure. Free speech empowers citizens to shape their society, while the rule of law ensures that power remains accountable and justice prevails. Their historical roots – from the Magna Carta to modern constitutions – demonstrate a long struggle to balance liberty and order, a struggle that continues today. As threats evolve, from technological disruptions to political upheaval, the preservation of these principles demands active defense by citizens, lawmakers, and institutions alike. Only through their symbiosis can democracy remain a system where, in the words of Abraham Lincoln, government “of the people, by the people, for the people” does not perish from the earth.