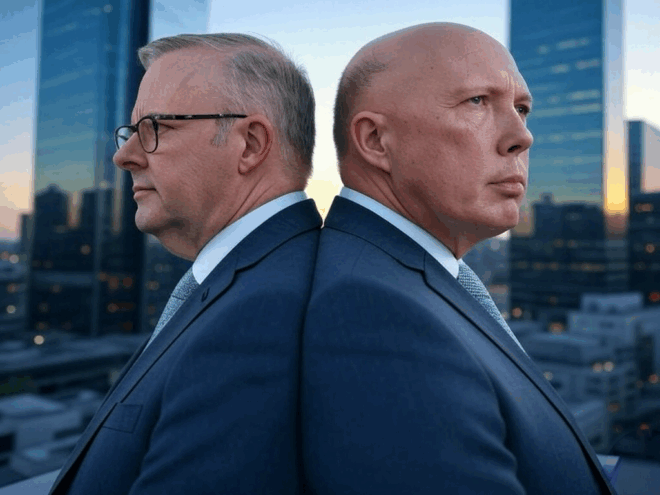

Australian politics has long been characterised by a dichotomy dominated by the Labor Party and the Liberal-National Coalition. In recent years, this has manifested through leaders like Anthony Albanese and Peter Dutton, who serve as archetypes of a political landscape that often prioritises careerism over genuine vision. Both politicians, products of their respective party machinery, exemplify a troubling trend of mediocrity in political leadership, where loyalty to party structures often eclipses innovation and authentic public service. This mediocrity, deeply embedded in the insularity of major party pre-selections and the convergence of policy agendas, has led to widespread public disillusionment, threatening the vitality of Australia’s democracy.

As we approach the upcoming federal election on May 3, 2025, there is a palpable sense of potential for change. A growing wave of independent candidates is emerging to challenge the entrenched two-party stranglehold. These candidates, often supported by grassroots movements and driven by community priorities, have the capacity to reinvigorate political engagement and diversify representation in the Australian Parliament. However, they must navigate systemic barriers to succeed. This essay posits that the mediocrity exemplified by leaders like Albanese and Dutton is a symptom of a flawed political system, and the rise of independents represents a critical opportunity to break this cycle, fostering a more dynamic and responsive democracy.

The Mediocrity of Australian Political Leadership

At the forefront of this mediocrity are figures like Peter Dutton and Anthony Albanese, both quintessential career politicians moulded by their respective party establishments. Dutton, a former Queensland policeman who entered federal parliament in 2001, has ascended through the ranks of the Liberal Party by adhering to loyalty, hardline conservatism, and strategic alliances. His tenure as Home Affairs Minister and later as Opposition Leader has been marked by a focus on divisive issues such as immigration and national security, often prioritising political point-scoring over nuanced solutions. Analysts have described his rhetoric as “combative,” which resonates with the Liberal base but alienates moderates, thereby limiting his broader appeal.

In parallel, Albanese, a steadfast Labor member since his youth, has navigated the treacherous waters of factional battles and union influences to become Prime Minister in 2022. His leadership style has been characterised as cautious and risk-averse, drawing criticism for its lack of bold vision on pressing issues such as climate change, housing affordability, and Indigenous affairs. His incremental approach – evident in the watered-down Indigenous Voice to Parliament and modest emissions reduction targets – prioritises party unity over transformative change, further exemplifying the limitations of career politicians.

Both Dutton and Albanese represent the limitations of a political class cultivated within insular party ecosystems that reward conformity over creativity. The processes of preselection within the Liberal and Labor Parties favour insiders – individuals who have spent years entrenched in factional structures – while sidelining outsiders who might offer fresh perspectives. This self-perpetuating cycle allows only the ambitious yet unremarkable to dominate, resulting in a political class that views governance as a career ladder rather than a calling. As the adage goes, “Mediocrity is excellence in the eyes of mediocre people,” and Australia’s political system seems to have internalised this principle, elevating figures adept at navigating internal party politics rather than addressing the complex challenges facing the nation.

This mediocrity is not limited to Dutton and Albanese but reflects a broader malaise in Australian politics. Policy debates frequently lack depth, with both major parties converging on centrist, risk-averse positions to avoid alienating swing voters. For instance, on climate change, Labor’s target of a 43% reduction in emissions by 2030 and the Coalition’s resistance to ambitious renewable energy policies both fall short of the urgency demanded by scientists. Similarly, on housing affordability – a critical concern for younger voters – neither party has proposed bold reforms to address negative gearing or supply constraints, opting instead for incremental measures that preserve the status quo. This convergence stifles meaningful choice, leaving voters feeling that elections yield little change. The resulting disillusionment is reflected in declining trust in politicians, with a 2024 Lowy Institute poll indicating that only 29% of Australians express confidence in federal parliament, a significant drop from 43% a decade ago.

The consequences of this mediocrity extend beyond mere voter apathy; they threaten the health of Australia’s democracy itself. Compulsory voting masks deeper disengagement, as evidenced by the rising rate of informal votes, which reached 10.3% in the 2022 election, signaling frustration with the available options. If the political landscape continues to attract and reward careerists, the risk is a democracy that fails to adapt to pressing challenges, ranging from economic disruption to environmental crises. The major parties’ reliance on corporate donors and union affiliations further entrenches this stagnation, with policy decisions often shaped by vested interests rather than public needs. Without systemic change, Australian politics risks remaining a “sea of mediocre politicians,” where figures like Dutton and Albanese are not exceptions but rather the norm.

The Rise of Independent Candidates

The growing disillusionment with the major parties has created fertile ground for independent candidates, who are poised to play a significant role in the 2025 election. These candidates, often supported by grassroots movements, reject the careerism and party loyalty exemplified by Albanese and Dutton, instead offering a vision of politics driven by community priorities and substantive policy. The 2022 election marked a turning point, with a record 16 crossbench members in the House of Representatives, including 13 independents, reflecting a shift away from the two-party system. A YouGov poll projects that independents and minor parties could increase their vote share to 8.3% in 2025, up from 5.3% in 2022, driven by voters seeking alternatives to the “ALP/LNP duopoly.”

Independent candidates in 2025 will represent a diverse array of backgrounds, ranging from community activists to professionals, united by their rejection of traditional party politics. They include:

• Teal Independents: Candidates such as Zoe Daniel (Goldstein), Monique Ryan (Kooyong), and Kate Chaney (Curtin) target affluent urban seats historically held by Liberals. Labelled “Teals” for their blend of progressive social policies and economic moderation, they emphasise climate action, gender equality, and anti-corruption measures. Zali Steggall, who unseated Tony Abbott in Warringah in 2019, set a precedent for challenging high-profile Liberals, and in 2025, Teals will contest seats like Bradfield and Mackellar, leveraging local discontent with the Coalition’s climate inaction.

• Rural and Regional Independents: Figures like Helen Haines (Indi) and Andrew Wilkie (Clark) focus on regional issues such as healthcare, housing, and economic development. Sue Chapman, a local surgeon challenging the Liberal stronghold in Forrest (WA), cites neglect of regional infrastructure as a key issue. Similarly, Andrew Gee, who defected from the Nationals to run as an independent in Calare, is capitalising on rural voters’ frustration with the major parties.

• Community-Driven Candidates: Dai Le, the first Vietnamese-Australian refugee elected to parliament (Fowler, 2022), represents culturally diverse electorates and prioritises cost-of-living relief and local services. New candidates like Stewart Brooker (Fadden) and Kirstie Smolenky (Groom) in Queensland are tapping into anti-major party sentiment in suburban and regional areas.

• Senate Independents: David Pocock, who won an ACT Senate seat in 2022, exemplifies the potential for independents to influence the upper house. His focus on anti-corruption and climate action resonates with progressive voters. Fatima Payman, a former Labor senator running under her Australia’s Voice party, is targeting Western Australian Senate seats, appealing to multicultural communities.

These candidates share a commitment to grassroots engagement, transparency, and issue-based campaigns, contrasting sharply with the top-down strategies of major parties. Their independence allows them to tailor policies to local needs, bridging “niche local issues” with national priorities such as housing and climate change. For instance, Zoe Daniel’s campaign in Goldstein emphasises coastal erosion and renewable energy, while Dai Le focuses on childcare and small business support in Fowler’s diverse communities.

Strategies and Challenges for Independents

Independent candidates rely on grassroots campaigns to overcome the financial and structural advantages enjoyed by major parties. Successful campaigns, such as Cathy McGowan’s 2013 victory in Indi, emphasise door-knocking, community forums, and corflutes to build local momentum. The “Voices Of” model, which empowers communities to select candidates through town halls and surveys, has proven pivotal in seats like Indi and Warringah. Climate 200, a fundraising group founded by Simon Holmes à Court, has transformed the independent landscape by supporting 23 candidates in 2022, including 10 who won seats, providing essential funding, polling, and marketing resources. This “party-like” coordination, as described by political scientist Mark Riboldi, allows independents to compete with entrenched party machines without adopting rigid party structures.

However, independents face significant challenges:

• Financial Barriers: Major parties benefit from established donor networks and public funding, with Labor and the Coalition each receiving over $20 million in public funding in 2022. Independents, in contrast, rely on crowdfunding or groups like Climate 200, which raised $13 million in 2022 but faces scrutiny over donor transparency. Running a competitive campaign necessitates substantial resources, often out of reach for lesser-known candidates.

• Electoral System: Australia’s preferential voting system can benefit independents by allowing vote transfers, but candidates need at least 10% of the primary vote to be viable for preferences. Safe seats, historically held by one party, are challenging to flip without a major scandal or the retirement of an incumbent. For example, Dutton’s seat of Dickson, with an 8.9% margin, presents a tough target despite independent campaigns.

• Voter Skepticism: Some voters, wary of “party-like” behaviour among Teals, question whether independents are truly independent or merely a new faction. Posts on social media platforms highlight concerns about candidates’ backgrounds and preference flows, urging voters to research independents carefully. For instance, Climate 200’s funding has sparked debates about whether Teals are beholden to wealthy donors.

• Major Party Pushback: Both Labor and Liberal are actively targeting independent-held seats. In Forrest, the Liberals have deployed high-profile figures like Dutton to bolster their candidate, while Labor is contesting seats like Indi and Goldstein to reclaim progressive votes. The Coalition has also adopted Teal-like strategies, emphasising local candidates and climate rhetoric to neutralise independent appeals.

Despite these hurdles, the decline in major party support – down to a combined 68.3% in 2022 – creates opportunities for independents. Analysts predict a hung parliament, where a larger crossbench could hold the balance of power, amplifying the influence of independents. Over 100 independents are running in 2025, targeting both safe seats like Dickson and marginal seats like Calare and Monash, where incumbents like Andrew Gee and Russell Broadbent have defected from major parties.

The Roots of Mediocrity in the Political System

The mediocrity of Australian politics, as exemplified by Dutton and Albanese, is deeply rooted in the structural flaws of the major parties’ candidate selection processes. Both Liberal and Labor prioritise loyalty and longevity, creating a pipeline of career politicians who rise through factional networks rather than merit or innovation. Pre-selections are often controlled by party insiders, with candidates chosen for their ability to conform to party lines rather than their expertise or vision. For instance, Dutton’s hardline stance on immigration aligns with the Liberal Party’s conservative base, while Albanese’s factional balancing act ensures Labor’s internal cohesion but limits bold policymaking. This insularity produces a political class that is homogenous – predominantly white, male, and middle-aged – with limited representation of diverse professions or backgrounds.

The influence of corporate donors and unions further entrenches this mediocrity. In 2022, the major parties received millions in donations from fossil fuel companies, property developers, and unions, shaping policy priorities that favour vested interests over public needs. For example, Labor’s reluctance to reform negative gearing reflects pressure from property lobbies, while the Coalition’s resistance to renewables aligns with fossil fuel donors. This dynamic stifles debate and innovation, as career politicians like Dutton and Albanese prioritise donor satisfaction and electoral survival over long-term challenges such as climate change or wealth inequality.

The media also plays a role in perpetuating mediocrity, often focusing on political theatre – Dutton’s provocations or Albanese’s gaffes – rather than substantive policy analysis. Soundbites and scandals dominate coverage, rewarding leaders who excel at media management rather than governance. This environment discourages risk-taking, as politicians fear backlash from sensationalist reporting or social media pile-ons. The result is a political culture that values conformity and caution, producing leaders who are competent within party constraints but lack the courage or imagination to tackle complex issues.

The Consequences of Mediocrity

The mediocrity of Australian political leadership has tangible consequences for policy and public trust. On climate change, Australia lags behind global peers, with neither major party committing to net-zero by 2040, despite warnings from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC). Housing affordability remains a crisis, with median home prices in Sydney exceeding $1.5 million, yet both parties avoid structural reforms like changes to capital gains tax. Indigenous affairs, too, have stagnated, with the failure of the Voice referendum exposing a lack of bold leadership on reconciliation. These failures reflect a broader inability to prioritise long-term national interests over short-term political gains.

Public disengagement is another consequence, with informal votes and protest votes for minor parties rising. A 2024 Australian Electoral Commission report noted that 12% of voters in marginal seats cast informal ballots, a sign of frustration with major party offerings. Social media platforms amplify this sentiment, with users decrying the “ALP/LNP duopoly” and calling for alternatives. If this trend continues, Australia risks a democracy where participation is driven by obligation rather than enthusiasm, undermining the legitimacy of elected governments.

The Potential Impact of Independents

The rise of independent candidates could transform Australian politics in several significant ways, addressing the shortcomings of the current system:

1. Increased Representation: Independents bring diverse voices to parliament, countering the homogeneity of career politicians. Candidates like Dai Le, advocating for multicultural communities, Helen Haines, focusing on rural healthcare, and Zoe Daniel, emphasising coastal sustainability, reflect a broader range of lived experiences than the typical party insider.

2. Policy Innovation: Free from party constraints, independents can propose bold solutions. For example, David Pocock and Helen Haines championed a federal anti-corruption commission, a policy stalled by major parties until public pressure forced action. Teal independents have also advocated for a 60% emissions reduction target by 2035, outpacing Labor’s commitments.

3. Voter Engagement: Grassroots campaigns rekindle public interest in politics, countering apathy. The “Voices Of” movement, which empowers communities to select candidates, fosters participatory democracy, with over 10,000 volunteers involved in the 2022 campaigns. Community forums and town halls create direct connections between candidates and voters, bypassing traditional media filters.

4. Challenging the Two-Party System: A larger crossbench could compel Labor and the Coalition to negotiate, leading to more collaborative governance. In a hung parliament, independents like Zoe Daniel or Helen Haines could act as kingmakers, shaping policy priorities. This dynamic could disrupt the cycle of policy convergence, encouraging competition and innovation.

However, the impact of independents will depend on their ability to deliver tangible outcomes. If they fail to translate campaign promises into results, voters may revert to major parties, viewing independents as ineffective. The “Teal” label also risks alienating voters who perceive it as a quasi-party, undermining the independent brand. Social media discussions reflect this tension, with some praising Teals for their climate focus while others question their reliance on Climate 200 funding.

The 2025 Election: A Turning Point?

The 2025 election will serve as a litmus test for the durability of the independent movement. With over 100 independents running, targeting both safe seats like Dickson (Dutton’s electorate, 8.9% margin) and marginal seats like Calare (currently independent-held) and Monash (where Russell Broadbent defected from the Liberals), the stakes are high. Polls suggest independents could secure victories in regional seats such as Cowper and Calare, building on the momentum of the 2022 “Teal wave.” Key battlegrounds include:

• Forrest (WA): Sue Chapman’s campaign highlights local neglect, challenging Liberal dominance with a focus on healthcare and infrastructure.

• Queensland Seats: Candidates like Stewart Brooker (Fadden) and Paul McKeown (Fairfax) aim to capitalise on anti-major party sentiment in suburban and regional areas, where cost-of-living pressures are acute.

• Senate Races: David Pocock’s re-election bid in the ACT and Fatima Payman’s Australia’s Voice party in Western Australia could diversify the upper house, amplifying progressive voices.

A hung parliament, considered likely by analysts such as Kos Samaras, would elevate the crossbench’s role, potentially requiring Albanese or Dutton to govern with independent support. This scenario could enhance the influence of figures like Zoe Daniel or Helen Haines, who have established reputations for principled negotiation. For example, Daniel’s work on climate adaptation and Haines’ advocacy for regional equity could shape coalition agreements, prioritising issues sidelined by major parties.

The Senate, too, presents opportunities for independents to influence policy. Pocock’s 2022 victory demonstrated that independents can secure upper house seats by appealing to progressive voters disillusioned with Labor and the Greens. Payman’s campaign, which focuses on multicultural inclusion and social justice, could resonate in Western Australia, where Labor’s dominance is waning. A diverse Senate crossbench could act as a check on major party legislation, ensuring greater scrutiny and accountability.

Systemic Changes Needed

While independents offer hope for renewal, systemic changes are essential to address the root causes of mediocrity in Australian politics. The major parties must reform their preselection processes to attract diverse, independent-minded candidates – scientists, entrepreneurs, educators, or community organisers – who bring expertise and fresh perspectives. This requires reducing the influence of factions, unions, and corporate donors, who often gatekeep access to political careers. For example, Labor could adopt open primaries, as trialed in some U.S. states, to democratise candidate selection, while the Liberals could prioritise merit-based criteria over factional loyalty.

Political discourse must also evolve to reward substance over soundbites. Media outlets should focus on policy analysis rather than sensationalist coverage, encouraging leaders to tackle complex issues with honesty. Voters, too, play a crucial role in demanding accountability, utilising platforms like social media to amplify substantive debates and reject cynicism. Public funding for campaigns could level the playing field, reducing independents’ reliance on groups like Climate 200 and ensuring broader access to political participation.

Electoral reforms could further empower independents. Lowering the deposit required to run for office (currently $2,000) would encourage more candidates, while caps on campaign spending could diminish the financial advantage of major parties. Strengthening the Australian Electoral Commission’s oversight of donations would enhance transparency, addressing concerns about donor influence over both parties and independents.

The Risks of Inaction

If Australian politics fails to embrace these changes, the consequences could be profound. A continued reliance on career politicians like Dutton and Albanese risks further eroding public trust, particularly among younger voters – already disillusioned by housing and climate inaction – who may disengage entirely. The rise of populist minor parties, such as One Nation or Clive Palmer’s United Australia Party, could fill the void, offering simplistic solutions that exacerbate division rather than address root causes. A 2024 study by the Australian National University found that 15% of voters are open to populist alternatives, a trend that could intensify if major parties remain stagnant.

A fragmented parliament, while empowering independents, also carries risks. Without clear leadership, policymaking could slow, delaying action on urgent issues such as climate adaptation or economic inequality. Independents must balance local priorities with national cohesion, avoiding the perception of parochialism. Their success will depend on building coalitions – both among themselves and with minor parties like the Greens – to amplify their influence.

Conclusion

Peter Dutton and Anthony Albanese, as products of the Liberal and Labor Party machines, embody the mediocrity that has come to define Australian politics. Their reliance on factional loyalty and risk-averse governance reflects a system that prioritises careerism over vision, stifling innovation and eroding public trust. The rise of independent candidates in the 2025 federal election presents a critical opportunity to break this cycle, introducing diverse voices, bold policies, and grassroots energy into a stagnant political landscape. From Teal independents in urban seats to community-driven candidates in regional areas, these challenges are redefining representation, prioritising issues like climate change, housing, and integrity over party agendas.

However, the success of independents hinges on their ability to overcome financial, electoral, and perceptual barriers, as well as sustaining voter support beyond the election. Systemic reforms – within party pre-selections, campaign funding, and political discourse – are essential to ensure that Australian politics attracts leaders of substance rather than mediocrity. If voters embrace this shift and the crossbench grows, the 2025 election could mark a turning point, fostering a more dynamic and responsive democracy. Failure to seize this moment risks entrenching the status quo, where career politicians like Dutton and Albanese continue to dominate, and Australia’s democratic vitality fades. The choice lies with voters, who must decide whether to uphold a sea of mediocrity or chart a new course toward a politics that truly serves the nation’s interests.