The concept of the Faustian bargain has long captivated the Western imagination, embodying the eternal struggle between desire and moral integrity. This cultural motif, originating from the legend of Faust, a scholar who trades his soul to the devil Mephistopheles for unfettered knowledge and worldly pleasures, serves as a profound metaphor for humanity’s relentless pursuit of fulfilment at potentially devastating costs. At its heart, the Faustian bargain raises an essential question: what is our self really worth?

In this exploration, we delve into Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Faust, a literary masterpiece that transcends its cautionary roots to explore themes of human striving, existential longing and the possibility of redemption. Goethe’s dynamic interplay between Faust and Mephistopheles not only sheds light on the moral conflicts inherent in the human condition, but also resonates with contemporary issues, particularly the West’s alliance with Zionism. In this context, Gaza emerges as a symbolic representation of the “soul” sacrificed in the name of geopolitical ambition. This post aims to weave together the intricate threads of the Faustian bargain, Goethe’s philosophical insights and the implications of modern alliances into a cohesive narrative that challenges us to reflect on the worth of our collective self.

The Faustian Bargain: A Cultural and Philosophical Framework

The Faustian bargain, immortalised in literary works such as Christopher Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus and Goethe’s Faust, encapsulates humanity’s perennial temptation to trade the intangible for the tangible. Marlowe’s protagonist, Faustus, makes a fateful pact for 24 years of supernatural power, ultimately facing the tragic irony of eternal damnation. In despair, he famously laments, “I’ll burn my books!”, a poignant reminder that the fleeting gains of ambition cannot outweigh the eternal loss of one’s soul.

Conversely, Goethe re-imagines this narrative, transforming it into a philosophical epic that emphasises the potential for redemption through striving. The universal appeal of the Faustian motif transcends cultural boundaries, echoing in Buddhist tales of temptation and various mythologies where deals with trickster gods highlight the human struggle with desire and morality. The price remains constant: the soul, the essence of identity, is at stake.

In a contemporary context, the West’s support for Zionism exemplifies a modern manifestation of the Faustian bargain. Rooted in strategic interests and historical guilt, this alliance offers geopolitical leverage and moral capital at a grave cost: the suffering of over 2 million people in Gaza. This reality prompts us to confront the moral erosion of democratic ideals, compelling us to ask, what is our self really worth?

Goethe’s Faust: A Reimagining of the Faustian Bargain

Goethe’s Faust, divided into two parts, transforms the Faustian legend into a profound exploration of human aspiration. Part I focuses on Faust’s personal desires, particularly his tragic seduction of Gretchen, while Part II expands into a cosmic allegory encompassing power, beauty and Utopian vision. The work’s varied poetic forms, from knittelvers to classical meters, reflect Faust’s boundless ambition and the tension between high art and folkloric roots.

Faust, a disillusioned scholar, begins his journey lamenting the limits of human knowledge: “I’ve studied now Philosophy / And Jurisprudence, Medicine, / And even, alas! Theology, / All through and through with ardour keen! / Here now I stand, poor fool and see / I’m just as wise as formerly.” His internal conflict – between earthly pleasures and spiritual fulfilment – drives him to magic and ultimately to a pact with Mephistopheles, who offers unlimited experiences in exchange for Faust’s soul. Unlike Marlowe’s Faustus, who seeks power for its own sake, Goethe’s Faust is in search of existential meaning, transforming his bargain into a quest for transcendence.

The tragedy of Gretchen grounds this quest in human suffering. Faust’s seduction, facilitated by Mephistopheles’ manipulations, leads to a series of tragic events: the death of Gretchen’s mother, the murder of her brother, the infanticide and her subsequent imprisonment. In stark contrast, Gretchen’s spiritual redemption highlights Faust’s moral ambiguity, illustrating the tension between desire and ethics. Part II broadens the narrative scope, with Faust pursuing political power, classical beauty (symbolised by Helen of Troy) and a vision for a Utopian society. Ultimately, Faust’s striving earns him divine grace, as angels proclaim, “Whoever strives, we can redeem,” thus saving his soul from Mephistopheles.

Goethe’s Faust bridges the Enlightenment and Romantic eras, affirming human potential through the act of striving. Its redemptive arc sets it apart from Marlowe’s tragedy, offering a hopeful vision that resonates with the West’s potential for moral redemption by addressing the suffering in Gaza.

Faustian Themes in Goethe’s Faust

Goethe’s Faust intricately weaves several core themes that illuminate the stakes of the Faustian bargain:

1. Pursuit of Infinite Knowledge and Experience: Faust’s discontent with the limitations of scholarly pursuits propels him into a pact, reflecting humanity’s desire to transcend boundaries. His pursuits – love, power, beauty – echo the West’s geopolitical ambitions in Zionism, where strategic dominance often comes at Gaza’s expense.

2. Conflict Between Desire and Morality: The tragic consequences of Faust’s seduction of Gretchen reveal the moral costs of unchecked desire. Similarly, the West’s support for Israel often prioritises power over human rights, undermining ethical principles.

3. Hubris and Human Limits: Faust’s belief that he can outsmart Mephistopheles embodies hubris, mirroring the West’s assumption that it can navigate Middle Eastern complexities without facing moral repercussions.

4. Redemption Through Striving: Faust’s eventual salvation through relentless aspiration offers a glimmer of hope. The West can redeem its moral “soul” by advocating for justice in Gaza, prioritising human dignity over strategic gains.

5. Universality of the Bargain: The Faustian motif transcends its Christian origins, resonating with global narratives of temptation. The West’s alliance with Zionism represents a modern iteration of this bargain, with Gaza’s suffering serving as a universal call to recognise the value of the self.

These themes frame Faust’s journey as a microcosm of human struggle, with Mephistopheles’ influence acting as a pivotal force.

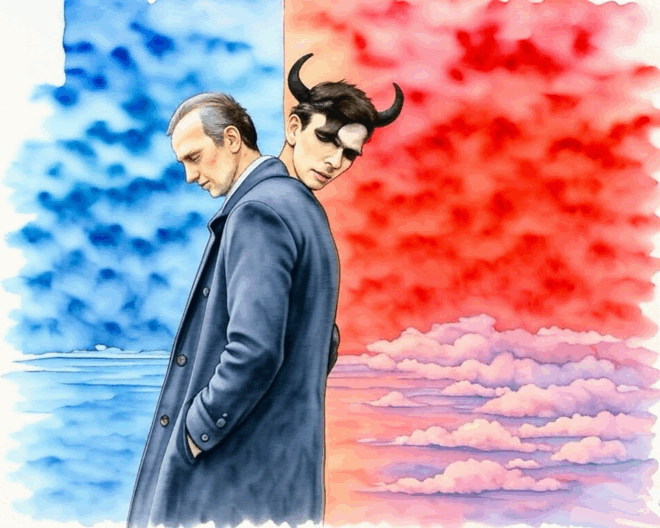

Faust and Mephistopheles: A Comparative Analysis

Faust and Mephistopheles embody contrasting yet interdependent forces: aspiration versus negation.

• Motivations: Faust seeks meaning, driven by existential discontent. His wager with Mephistopheles evolves from a quest for love (Gretchen) to aspirations of legacy (utopia). In contrast, Mephistopheles, the “spirit that negates,” aims to undermine creation, asserting that all existence “deserves to perish.” His wager hinges on Faust’s susceptibility to superficial desires.

• Characteristics: Faust is a complex figure, torn between intellect and passion, capable of hubris and remorse. His evolution reflects human growth, culminating in redemption. Mephistopheles, however, remains static – witty and cynical, yet devoid of emotional depth. His unchanging nature starkly contrasts with Faust’s adaptability.

• Roles: Faust propels the narrative through his choices, representing humanity’s quest for meaning. Mephistopheles serves as the catalyst, facilitating Faust’s desires while simultaneously seeking his downfall. Their symbiotic relationship – Faust’s reliance on Mephistopheles’ temptations and Mephistopheles’ dependence on Faust’s actions – mirrors the West’s reliance on policies that pursue Zionism’s strategic goals.

• Philosophical Significance: Faust embodies Enlightenment and Romantic ideals of potential and autonomy, affirming the soul’s value through striving. In contrast, Mephistopheles’ nihilism challenges Faust to justify existence, reflecting the West’s moral tension between the aspiration for power and the negation of Gaza’s humanity.

Their relationship serves as a dialectic, with Mephistopheles’ influence shaping Faust’s path while inadvertently fostering his eventual salvation – a dynamic central to the work’s exploration of the self’s worth.

Mephistopheles’ Philosophy: Nihilism and Negation

The philosophy of Mephistopheles is foundational to his influence, characterised by four key tenets:

1. Nihilism: His assertion, “I am the spirit that negates / And rightly so, for all that comes to be / Deserves to perish wretchedly,” underscores a worldview in which existence is ultimately futile. This nihilism anticipates existentialist philosophies, challenging the value of human endeavours.

2. Cynicism Toward Aspiration: Mephistopheles derides Faust’s striving, reducing desires to mere gratification. He lures Faust with pleasures, confident that they will ensnare him, as demonstrated in his dismissive remark, “She’s not the first,” after Gretchen’s tragic demise.

3. Opposition to Divine Order: In the “Prologue in Heaven,” Mephistopheles debates the Lord, critiquing humanity’s misery. His role as a tolerated adversary suggests that negation is a necessary element of progress, reflecting a pantheistic view where conflict drives evolution.

4. Relativism and Amorality: Mephistopheles rejects absolute values, manipulating others without remorse. His indifference to the suffering he causes – evident in the tragedies of Gretchen and Philemon and Baucis – reveals a worldview where actions lack intrinsic meaning.

The implications of Mephistopheles’ philosophy challenge Faust – and the audience – to defend the worth of the self against nihilism. His failure to claim Faust’s soul ultimately illustrates the limits of negation, affirming Goethe’s optimistic vision. In the context of the West’s Faustian bargain, Mephistopheles’ nihilism parallels policies that devalue the lives of Gazans, treating their suffering as collateral damage in a strategic game.

Mephistopheles’ Influence: Catalyst and Destroyer

Mephistopheles’ influence is multifaceted, shaping not only Faust and other characters but also the narrative and its symbolic dimensions.

• On Faust: Mephistopheles ignites Faust’s journey, facilitating his desires through supernatural means – rejuvenation, political power and the summoning of Helen. His cynical philosophy tests Faust’s values, leading to moral lapses that paradoxically foster Faust’s growth and eventual redemption.

• On Other Characters: Mephistopheles devastates Gretchen, orchestrating her seduction and downfall, yet her redemption stands in defiance of his nihilism. He causes the deaths of Philemon and Baucis and corrupts the Emperor’s court, amplifying the collateral costs of the bargain.

• Narrative Function: As a catalyst for key events – from the initial pact to Faust’s Utopian aspirations – Mephistopheles introduces a balance of tragedy and humour. His philosophical debates frame the narrative as an inquiry into existence and morality.

• Symbolic Significance: Mephistopheles embodies temptation, negation and societal corruption, externalising Faust’s desires while critiquing human flaws. His role as a necessary evil aligns with Goethe’s view of progress through conflict.

Limitations: Mephistopheles and the Divine Order

Despite his influence, Mephistopheles is constrained by divine order and human resilience. The Lord’s tolerance and Faust’s ultimate salvation underscore his subordination to the forces of creation. His self-defeating nature – enabling the striving that redeems Faust – highlights the inherent limits of negation.

Modern Parallel: The West’s Faustian Bargain

The relationship between the West and Zionism, deeply rooted in historical contexts such as the Balfour Declaration, can be viewed as a contemporary Faustian bargain. The West’s pursuit of geopolitical influence, characterised by substantial military aid and selective moral outrage, mirrors Faust’s quest for power and meaning. The staggering annual military assistance of $3.8 billion from the U.S. to Israel, alongside Europe’s tempered criticisms, secures a foothold in a volatile region while neglecting the humanitarian crisis unfolding in Gaza. Over 2 million Palestinians endure unimaginable suffering – blockades restricting access to basic necessities, military operations resulting in staggering death tolls and systemic deprivation eroding any semblance of hope.

In this context, Gaza represents the West’s “soul,” embodying the moral fabric of democratic ideals – justice, equality and compassion – sacrificed on the altar of geopolitical expediency. The policies enabling Israel’s actions reflect Mephistopheles’ amoral influence, treating the suffering of Gazans as collateral damage in a broader strategic game. Each airstrike, each child lost and each family displaced serves as a stark reminder of the moral erosion that accompanies such alliances.

Yet, the narrative does not end in despair. Goethe’s vision of redemption through striving offers a pathway for the West to reclaim its moral integrity. Just as Faust’s salvation hinges on his relentless pursuit of higher ideals, the West has the opportunity to redeem its “soul” by prioritising justice – advocating for a ceasefire, lifting blockades and supporting Palestinian rights. The global outcry, manifested through protests, UN resolutions and grassroots movements, parallels the divine grace that saves Faust, urging the West to confront its complicity and act decisively.

Culturally, the Faustian theme is everywhere.

Movies, books and even tech debates reflect our obsession with ambition’s price. Meanwhile, the West’s moral identity is under scrutiny, especially with social media shining a spotlight on Gaza’s suffering. It’s almost like the universe is saying, “Hey, remember that time you sold your soul for power?”

Philosophically, Goethe’s Faust wrestles with existential dilemmas that resonate today.

Mephistopheles’ nihilism challenges our striving for meaning – much like Nietzsche’s Übermensch and Kierkegaard’s despair. Meanwhile, the ethical implications of the West’s actions raise eyebrows: is Gaza’s suffering a necessary evil for regional stability? Or should we just take a moment to embody justice and compassion?

Conclusion

The narrative of Faust is a timeless reminder of the struggle between aspiration and morality. As we navigate our own Faustian bargains, let’s ask ourselves: what is the true worth of our self? For Faust, it’s the relentless pursuit of higher ideals. For the West, it’s time to prioritise the humanity of Gaza’s people over fleeting gains.

So, as we face the moral dilemmas of our time, let’s remember: no deal is worth the cost of losing our humanity. After all, the lessons from Faust remind us to reflect on our actions and let compassion guide us. Because, in the end, isn’t that what really counts?