In shadows cast by history’s hand,

A tale unfolds, where truths withstand,

In frames of light, the past reclaims,

The echoes of forgotten names.

“Le Chagrin et la Pitié,” it speaks,

Of fractured lives, of sorrow’s peaks,

As time’s swift river bends and sways,

Each whispered tale anew displays.

A canvas rich with grief and grace,

Where choices haunt and fates embrace,

In every scene, a mirror’s gleam,

Reflecting now, a fractured dream.

Though decades pass and ages fade,

The art remains, its pulse conveyed,

For in each heart, the struggle stays,

A timeless truth in timely ways.

So let the world turn, let ages blend,

For in this film, our voices mend,

A masterpiece, not bound by time,

But ever relevant and sublime.

by Bakchos

Abstract

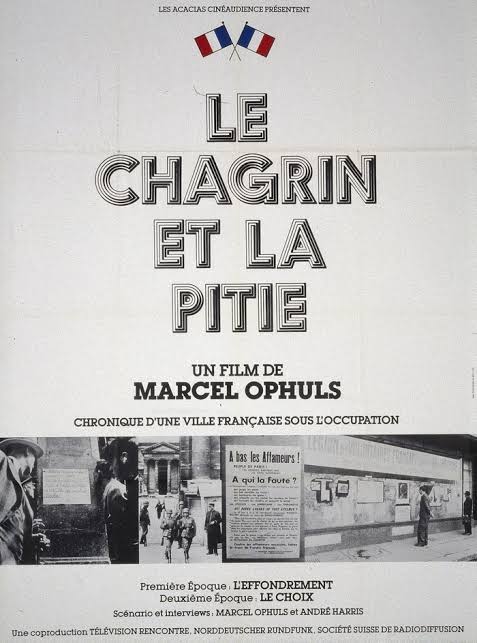

Marcel Ophuls’ Le Chagrin et la Pitié (The Sorrow and the Pity), released in 1969, stands as one of the most provocative and influential documentaries in the history of cinema. Its unflinching examination of French collaboration with Nazi Germany during World War II shattered the carefully curated postwar narrative of universal French resistance. The film, initially commissioned for French television but banned from broadcast, sparked intense controversy, with French authorities denouncing it as an assault on mainstream French culture and the mythos of postwar nationhood. By exposing the complicity of conservative French society in the Vichy regime’s collaborationist policies, Ophuls’ work was perceived as aligning with the radical leftist movements that had erupted in the streets of Paris in May 1968. This paper explores the historical and cultural context of The Sorrow and the Pity, its challenge to French national identity, its resonance with the political upheavals of the late 1960s and its lasting impact on historical memory and documentary filmmaking.

Introduction

The documentary, The Sorrow and the Pity, has significantly influenced how history is understood and represented, particularly in the context of France’s experience during World War II. By challenging the prevailing narrative of universal resistance, Ophuls’ film has ignited debates about national identity, historical memory and the moral complexities of individual choices in times of crisis. This research paper aims to explore the multifaceted dimensions of The Sorrow and the Pity, examining both the criticisms and accolades it has received and ultimately assessing its enduring legacy.

Historical Context: The Myth of the Resistance

To understand the seismic impact of The Sorrow and the Pity, one must first consider the historical and cultural landscape of postwar France. Following the liberation of France in 1944, the nation faced the daunting task of rebuilding not only its infrastructure but also its collective identity. The narrative of the French Resistance, led by figures like Charles de Gaulle, became a cornerstone of this reconstruction. De Gaulle, as the leader of the Free French Forces and later president of the Fifth Republic, promoted the idea that the vast majority of French citizens had resisted Nazi occupation, either actively or in spirit. This mythos, often referred to as the “Gaullist myth,” downplayed the extent of collaboration by the Vichy regime and ordinary citizens, portraying France as a nation united against the German occupiers.

The Vichy government, led by Marshal Philippe Pétain, had collaborated extensively with Nazi Germany from 1940 to 1944. It implemented anti-Semitic policies, including the deportation of over 75,000 Jews to concentration camps and supported the German war effort through economic and military contributions. Yet, in the immediate postwar years, France’s focus on national unity and reconstruction necessitated a selective memory. Trials of collaborators were held, but many were quickly reintegrated into society and the full scope of Vichy’s complicity was obscured. By the 1960s, this narrative had solidified, with school curricula, public commemorations and popular culture reinforcing the image of a heroic, resistant France.

The Genesis of The Sorrow and the Pity

Marcel Ophuls, the son of German-Jewish filmmaker Max Ophuls, brought a unique perspective to The Sorrow and the Pity. Born in Germany but raised in France and later exiled to the United States during the war, Ophuls had a personal connection to the era’s upheavals. His experience as an outsider informed his critical approach to French history. Commissioned by French television (ORTF) to create a documentary on the Occupation, Ophuls, along with co-director André Harris and producer Alain de Sédouy, set out to explore the lived experiences of ordinary French citizens during the war.

The resulting film, clocking in at over four hours, is a mosaic of interviews, archival footage and contemporary reflections. It focuses on the town of Clermont-Ferrand, a microcosm of French society under Vichy. Through conversations with former collaborators, resisters, bystanders and victims, Ophuls reveals the complexity of human behaviour during the Occupation. The film’s interviewees include a former Vichy official, a German officer stationed in France, a Jewish survivor and members of the Resistance, alongside ordinary citizens who navigated the moral ambiguities of wartime life. Archival propaganda films, newsreels and photographs are juxtaposed with these testimonies, creating a stark contrast between the official narrative and lived reality.

The Film’s Revelations and Narrative Structure

The Sorrow and the Pity is revolutionary not only for its content but also for its narrative structure. Unlike traditional documentaries of the era, which often relied on authoritative narration, Ophuls’ film allows its subjects to speak for themselves, with minimal editorialising. This approach lends authenticity and immediacy to the testimonies, forcing viewers to grapple with the moral dilemmas faced by individuals. The film is divided into two parts: “The Collapse,” which covers the fall of France in 1940 and the establishment of Vichy and “The Choice,” which examines the decisions made by individuals under occupation.

One of the film’s most striking revelations is the extent of voluntary collaboration. Interviewees recount how conservative elements of French society – landowners, businessmen and traditionalists – embraced Vichy’s “National Revolution,” which promised a return to traditional values in contrast to the perceived decadence of the Third Republic. Pétain’s regime was not merely a puppet state but a government with significant domestic support, particularly among those who feared communism and modernity. The film also exposes the complicity of ordinary citizens, from shopkeepers who denounced neighbours to bureaucrats who enforced anti-Semitic laws.

Equally powerful are the stories of resistance, which Ophuls presents not as heroic triumphs but as fraught, often isolating acts of courage. Resisters, such as the Grave brothers, describe the fear and betrayal they faced, even from fellow French citizens. The film’s refusal to glorify the Resistance challenges the Gaullist myth, presenting resistance as the exception rather than the rule.

The Political Climate of 1968 and the Film’s Reception

The release of The Sorrow and the Pity in 1969 came at a moment of profound political and cultural upheaval in France. The events of May 1968, when student protests and worker strikes nearly toppled the government, had exposed deep divisions within French society. The protests, led by leftist students and intellectuals, criticised the conservatism of de Gaulle’s government, its ties to traditional elites and its failure to address social inequalities. The Gaullist establishment, in turn, viewed the protests as a threat to national stability.

Against this backdrop, The Sorrow and the Pity was seen as a radical intervention. French authorities, particularly those aligned with Gaullism, denounced the film as an attack on national unity. The ORTF, which had commissioned the documentary, refused to broadcast it, citing its controversial content. The film was instead screened in a small Paris cinema, where it gained a cult following among intellectuals and leftists. Critics of the film argued that it unfairly tarnished France’s reputation by focusing on collaboration rather than resistance. Some accused Ophuls of bias, claiming that his Jewish background and leftist sympathies shaped the film’s perspective.

The perception that Ophuls was “taking the side of leftists” stemmed from the film’s alignment with the 1968 critique of conservative institutions. By exposing the collaborationist tendencies of France’s traditional elites, the film resonated with the protesters’ rejection of hierarchical, authoritarian structures. Moreover, its emphasis on individual agency and moral responsibility echoed the existentialist themes popular among the French left. For many viewers, the film was a call to confront uncomfortable truths about the past and present, challenging the complacency of postwar French society.

Cultural and Historical Impact

The controversy surrounding The Sorrow and the Pity marked a turning point in French historical memory. The film is widely credited with initiating a broader reckoning with the Vichy era, a process that historians refer to as the “Vichy syndrome.” In the 1970s and 1980s, scholars, filmmakers and writers began to explore the Occupation in greater depth, challenging the Gaullist narrative. Robert Paxton’s seminal book Vichy France: Old Guard and New Order (1972), which drew on archival evidence to document Vichy’s collaboration, was influenced by the debates sparked by Ophuls’ film. Similarly, Louis Malle’s film Lacombe, Lucien (1974) explored the moral ambiguities of collaboration, further eroding the myth of universal resistance.

The film’s impact extended beyond France. When it was released in the United States in 1972, it received critical acclaim, earning an Academy Award nomination for Best Documentary. American audiences, grappling with their own historical reckonings, such as the Vietnam War and the Civil Rights Movement, found the film’s exploration of complicity and resistance universally relevant. Woody Allen famously included a scene in Annie Hall (1977) where characters watch The Sorrow and the Pity, underscoring its cultural significance.

Ophuls’ Cinematic Legacy

The Sorrow and the Pity also transformed the documentary genre. Ophuls’ use of oral history, archival footage and a non-judgmental narrative style influenced generations of filmmakers. His later works, such as The Memory of Justice (1976) and Hotel Terminus (1988), continued to explore themes of historical memory and moral responsibility. The film’s emphasis on letting subjects speak for themselves paved the way for modern documentaries that prioritise authenticity and complexity over didacticism.

Ophuls’ approach was not without critics. Some argued that the film’s lack of explicit commentary left viewers to draw their own conclusions, potentially leading to misinterpretations. Others questioned whether the focus on Clermont-Ferrand was representative of France as a whole. Nevertheless, the film’s power lies in its ability to provoke discussion and self-reflection, forcing audiences to confront the grey areas of history.

The Lasting Relevance of The Sorrow and the Pity

More than five decades after its release, The Sorrow and the Pity remains a vital work of historical and cinematic art. Its exploration of collaboration and resistance resonates in contemporary debates about national identity, collective memory and the legacies of authoritarianism. In France, the film’s influence can be seen in ongoing discussions about Vichy’s role in the Holocaust, culminating in President Jacques Chirac’s 1995 acknowledgment of France’s responsibility for deporting Jews.

Globally, the film serves as a reminder of the fragility of moral courage in times of crisis. As societies grapple with issues such as xenophobia, populism and historical revisionism, The Sorrow and the Pity challenges us to examine our own complicity and agency. Its message is universal: history is not a monolithic narrative but a tapestry of individual choices, each carrying profound consequences.

Conclusion

Marcel Ophuls’ The Sorrow and the Pity is more than a documentary; it is a cultural and historical watershed that forced France to confront its wartime past. By revealing the extent of collaboration within conservative French society, the film dismantled the Gaullist myth of universal resistance, aligning with the radical critiques of the 1968 protests. Despite fierce opposition from French authorities, the film sparked a reckoning with the Vichy era, reshaping historical memory and influencing documentary filmmaking. Its enduring relevance lies in its unflinching honesty and its call to grapple with the complexities of human behaviour. In challenging France to face its sorrow and pity, Ophuls created a work that continues to inspire reflection and dialogue across generations and borders.