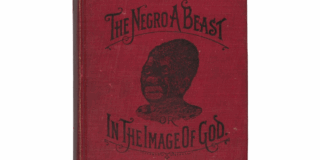

Racism, a malignant affliction of the human psyche, festers in the shadows of fear, ignorance and insecurity, corroding the bonds that hold societies together. In Australia, a nation lauded for its multicultural vibrancy, racism persists as a formidable obstacle, undermining aspirations for unity and equality. This sordid mindset transcends race, creed or class, manifesting in destructive ways that harm individuals and the collective. From the dispossession of Indigenous Australians to xenophobia against migrants and tensions within minority communities, racism’s historical roots and contemporary expressions reveal a complex web of prejudice. Multicultural policies have emerged as a cornerstone of Australia’s response, aiming to celebrate diversity, foster inclusion and counter bigotry’s divisive impact. Yet, despite significant strides, these policies often fall short of dismantling systemic inequities. This essay explores racism’s pervasive effects in Australia and evaluates the role of multicultural policies in addressing it, arguing that while a singular cultural identity is unattainable, robust policies ensuring equality of opportunity are essential to overcome racism’s drag and harness diversity for national progress.

Historical Context: The Foundations of Racial Division

Australia’s history is a tapestry of cultural richness marred by racial exclusion. The arrival of British settlers in 1788 unleashed a catastrophic era for Indigenous Australians, whose 60,000-year connection to the land was severed through violence, disease and dispossession. By the 19th century, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander populations had plummeted, with survivors subjected to forced labour, segregation and cultural erasure. The Stolen Generations policy, spanning the late 1800s to the early 1970s, forcibly removed tens of thousands of Indigenous children from their families to assimilate them into white society. The 1997 Bringing Them Home report documented the resulting intergenerational trauma, revealing wounds that continue to shape Indigenous experiences.

The 1901 White Australia Policy formalised racial hierarchy, restricting non-European immigration to preserve an Anglo-Saxon identity. This policy, rooted in fears of economic and cultural competition, was not dismantled until the 1970s. Early non-European migrants, such as Chinese gold rush arrivals in the 1850s, faced violent attacks and discriminatory taxes, while Pacific Islander labourers on Queensland’s sugar plantations were exploited and deported under the 1901 Pacific Island Labourers Act. These episodes reflect a pattern of exclusion driven by fear of “the other,” prioritising homogeneity over diversity.

Post-World War II labour shortages and global pressures to abandon colonial policies spurred change. The 1947 migration program welcomed displaced Europeans, diversifying the population. The Whitlam government’s abolition of the White Australia Policy in the early 1970s marked a pivotal shift, with Minister Al Grassby’s 1973 declaration of Australia as a “multicultural society” laying the groundwork for inclusive policies. The 1978 Galbally Report recommended migrant support services, while the 1989 National Agenda for a Multicultural Australia defined multiculturalism as a framework balancing cultural diversity with social cohesion, emphasising equality, mutual respect and civic participation.

Global events, such as the 2001 September 11 attacks and the 2005 Cronulla riots, tested this commitment, fuelling anti-Muslim sentiment and xenophobia. Subsequent policies, including the 2011 People of Australia and 2017 Multicultural Australia: United, Strong, Successful statements, refined multiculturalism to emphasise shared values and counter extremism. This evolution reflects Australia’s ongoing struggle to reconcile its diverse population with the legacy of racial division.

Contemporary Manifestations of Racism

Racism in modern Australia is a hydra with many heads, cutting across racial, ethnic and cultural lines. Indigenous Australians remain disproportionately marginalised, facing systemic disadvantages in health, education and justice. The 2020 Closing the Gap report revealed that only two of seven targets for improving Indigenous outcomes were on track, with a 10-year life expectancy gap and incarceration rates seven times the national average. Over 500 Indigenous deaths in custody since the 1991 Royal Commission into Aboriginal Deaths in Custody underscore systemic failures, with racial profiling feeling distrust. Public narratives often frame these issues as individual shortcomings, perpetuating stereotypes of Indigenous dysfunction.

Migrant communities also face prejudice. The 2005 Cronulla riots, where thousands of predominantly white Australians clashed with Middle Eastern communities in Sydney, exposed fears of cultural erosion, amplified by media sensationalism and post-9/11 anxieties. The COVID-19 pandemic triggered a surge in anti-Asian racism, with a 2021 Asian Australian Alliance report documenting over 600 incidents of harassment, from verbal abuse to physical assaults. These events highlight how economic insecurity, global crises and media distortions can inflame xenophobia.

Racism’s bidirectional nature adds complexity. Tensions between African and Pacific Islander communities in urban centres like Melbourne, often driven by competition for jobs or housing, have erupted into violence, challenging the notion that minority groups are immune to prejudice. Similarly, some established migrant communities, such as those from South Asia, express resentment toward newer arrivals like Sudanese or Syrian refugees, perceiving them as threats to economic stability. These dynamics reveal racism’s universal roots in fear, scarcity and cultural misunderstanding, underscoring the need for inclusive policies that address all forms of bigotry.

The Social and Economic Costs of Racism

Racism is not merely a moral failing; it is a tangible drag on Australia’s social cohesion and economic vitality. The 2019 Scanlon Foundation’s Mapping Social Cohesion survey found that 20% of Australians experienced racial or religious discrimination, with higher rates among non-European migrants and Indigenous people. This erodes trust, fostering alienation and division. The 2005 Cronulla riots and recent anti-Asian incidents illustrate how racism fractures communities, replacing shared identity with suspicion.

Economically, racism stifles innovation by marginalising talent. Indigenous Australians, 3.3% of the population, are underrepresented in higher education and professional sectors, with unemployment rates nearly three times the national average. A 2019 Australian National University study showed that job applicants with non-Anglo names are less likely to receive callbacks, even with identical qualifications. A 2018 Deloitte report estimated that cultural diversity contributes $1.6 trillion to Australia’s GDP, yet exclusion limits this potential, weakening competitiveness against nations like Japan, Korea and China, which leverage human capital effectively.

Radicalised fear of crime exacerbates these costs. Media portrayals of African “gangs” in Melbourne, despite crime statistics showing no disproportionate threat, have fuelled punitive policies and community division, diverting resources from education and integration. Stereotypes about Asian Australians as economic threats – evident in debates over foreign investment or property markets – ignore their contributions to entrepreneurship in suburbs like Box Hill or Chatswood. These distortions harm individuals and deprive the economy of diverse skills, a critical disadvantage in a globalised market.

Multicultural Policies: A Framework for Inclusion

Australia’s multicultural policies, implemented at federal, state and local levels, aim to counter racism by fostering inclusion and equality. Key components include:

1. Immigration and Settlement Services: Programs like the Adult Migrant English Program (AMEP) and Humanitarian Settlement Program (HSP) provide language training, employment support and cultural orientation. The HSP assists refugees with housing, healthcare and education, reducing integration barriers. For example, HSP support in regional areas like Shepparton has enabled refugees to thrive in agribusiness.

2. Anti-Discrimination Legislation: The Racial Discrimination Act 1975 (RDA) prohibits discrimination based on race, colour or ethnic origin, complemented by state laws like Victoria’s Racial and Religious Tolerance Act 2001. The Australian Human Rights Commission (AHRC) enforces these laws and runs campaigns like Racism. It Stops with Me, which has engaged over 500 organisations since 2012.

3. Cultural and Community Programs: Festivals like Harmony Day and Multicultural Arts Victoria’s events celebrate diversity, while grants support community organisations. The National Anti-Racism Strategy, renewed in 2021, promotes cultural competence through education and public engagement. The Federation of Ethnic Communities’ Councils of Australia (FECCA) advocates for migrant rights, amplifying diverse voices.

4. Indigenous Inclusion: Policies like Closing the Gap and the 2008 National Apology to the Stolen Generations address historical injustices, though they are often critiqued for limited impact. The Indigenous Procurement Policy, generating $1.8 billion for Indigenous businesses by 2022, shows promise but requires broader application.

5. Education and Media: Curricula emphasising Indigenous and migrant histories foster empathy, while the Special Broadcasting Service (SBS) delivers multilingual content to 7 million monthly viewers, challenging stereotypes. The ABC’s 2020 Australia Talks project revealed public support for diversity but highlighted discomfort discussing race, underscoring the need for cultural literacy.

These policies have yielded significant successes. The 2021 Census showed 27.6% of Australians were born overseas, with over 300 languages spoken, making Australia a global leader in diversity. The 2023 Scanlon survey found 85% of Australians view multiculturalism positively, with 66% reporting a strong sense of belonging. Migrant employment rates are high, with 67% of recent arrivals employed within five years, per the Department of Home Affairs. Economically, diversity drives growth and globally, Australia’s multicultural model enhances its reputation, attracting tourism, students and investment.

Limitations of Multicultural Policies

Despite these achievements, multicultural policies face significant challenges:

• Persistent Indigenous Inequality: Most Closing the Gap targets remain unmet, with Indigenous Australians facing systemic barriers in health, education and justice. Multicultural policies often treat Indigenous issues as separate, limiting their impact on closing disparities.

• Systemic Discrimination: A 2021 AHRC report noted that 20% of Australians experienced racial discrimination, with higher rates among Asian, African and Middle Eastern communities. Workplace biases persist and RDA enforcement is inconsistent, with only 15% of complaints leading to formal outcomes in 2020.

• Cultural Tensions: Policies struggle to navigate frictions, such as debates over Islamic schools or refugee resettlement. The 2005 Cronulla riots and anti-Asian incidents during COVID-19 reveal how fear and misinformation override policy efforts. Intra-community racism, like African-Pacific Islander conflicts, is rarely addressed.

• Policy Gaps: Underfunded settlement services, like AMEP, fail to meet the needs of refugees with trauma or low literacy. The 2023 Voice to Parliament referendum’s failure highlighted public resistance to structural reforms, with 60% voting against it.

• Media and Political Rhetoric: Sensationalist coverage of African “gangs” or Asian investors amplifies stereotypes, while political debates over immigration quotas fuel xenophobia. Policies lack robust mechanisms to counter these narratives, with only 10% of Racism. It Stops with Me campaign funds allocated to media reform in 2021.

These limitations reveal that while multicultural policies have built a foundation, they often fail to address racism’s socioeconomic roots or foster deep cultural understanding.

The Cultural Narrative: Beyond the Melting Pot

Australia’s cultural narrative oscillates between celebrating diversity and yearning for unity. The “melting pot” ideal, where cultures blend into a singular identity, is a fallacy. With over 200 ancestries and 300 languages, Australia is a mosaic, not a monolith. Indigenous cultures, Anglo-Celtic traditions and migrant identities coexist, creating richness but also friction. Cultural misunderstandings – over family structures, gender roles or religious practices – fuel prejudice, as seen in debates over halal certification or the 2017 marriage equality campaign, which polarised communities.

This diversity defies a shared cultural framework, but equality of opportunity can serve as a unifying principle. Without equitable access to education, employment and justice, marginalised groups compete for limited resources, fostering resentment that racists exploit. Multicultural policies must bridge these gaps to transform diversity into a cohesive strength, ensuring that cultural differences enhance rather than divide the nation.

Pathways Forward: Strengthening Policies to Combat Racism

To dismantle racism and enhance multicultural policies, Australia must adopt a bold, integrated approach:

1. Structural Reforms for Equity: Prioritise Closing the Gap targets and constitutional recognition for Indigenous Australians. Expand the Indigenous Procurement Policy model to other marginalised groups, ensuring economic inclusion. For example, extending procurement targets to refugee-owned businesses could replicate the $1.8 billion impact seen in Indigenous sectors.

2. Robust Anti-Discrimination Measures: Strengthen the RDA with stricter penalties and proactive audits, increasing conviction rates from 15% to 50% by 2030. Implement workplace diversity quotas and blind recruitment, building on Australian Public Service trials that increased minority hires by 20% in 2022.

3. Enhanced Settlement Support: Double AMEP and HSP funding, focusing on refugees with complex needs. Introduce mentorship programs pairing newcomers with established residents, as piloted in Adelaide, where 80% of participants secured employment within a year.

4. Education and Cultural Literacy: Mandate cultural competence training in schools and workplaces, with curricula emphasising Indigenous and migrant histories. Increase SBS and ABC funding by 25% to produce anti-racism content, reaching 10 million viewers monthly by 2030.

5. Community Dialogue and Media Reform: Scale initiatives like Victoria’s Interfaith Network and establish national anti-racism taskforces in every state. Penalise inflammatory media rhetoric with fines, allocating 50% of Racism. It Stops with Me funds to media reform. Target intra-community prejudice through campaigns like FECCA’s 2022 Unity Project, which reduced tensions in 70% of participating communities.

6. Economic and Global Alignment: Frame diversity as an economic asset, highlighting migrant contributions to tech and retail, which employ 1.2 million Australians. Align policies with national interests, leveraging the 2021 Lowy Institute poll showing 88% of Australians see multiculturalism as a strength to bolster public support.

7. Historical Reckoning and Truth-Telling: Establish a national truth-telling commission, as recommended by the 2017 Uluru Statement, to acknowledge colonial violence and educate the public. Pair this with reparative measures, such as land rights reforms, to address Indigenous dispossession.

8. Global Benchmarking: Learn from nations like Canada, where multiculturalism policies include mandatory diversity training for public servants, reducing workplace discrimination by 30%. Adapt such models to Australia’s context, ensuring policies remain dynamic and responsive.

These strategies can transform multicultural policies into a robust framework for equality, reducing racism’s corrosive impact and positioning Australia as a global model for diversity.

Conclusion

Racism in Australia, rooted in historical injustices and sustained by fear, ignorance and scarcity, undermines social cohesion and economic vitality. From Indigenous marginalisation to migrant harassment and intra-community tensions, its manifestations are diverse and destructive. Multicultural policies have made significant strides, fostering social cohesion, driving economic growth and enhancing Australia’s global reputation. However, persistent inequalities, systemic discrimination and cultural frictions reveal their limitations. Australia cannot forge a singular cultural identity, but it can unite around equality of opportunity. By confronting its past, strengthening anti-racism measures, fostering dialogue and aligning diversity with economic goals, Australia can harness its multicultural mosaic to overcome racism’s drag. The path is arduous, but the stakes are profound: a future where diversity is not just tolerated but celebrated as the nation’s greatest asset, paving the way for unity, prosperity and global leadership.

I appreciate your understanding and support as we navigate these important discussions. Let’s continue to engage with these topics thoughtfully and constructively.

Best regards,

Bakchos.