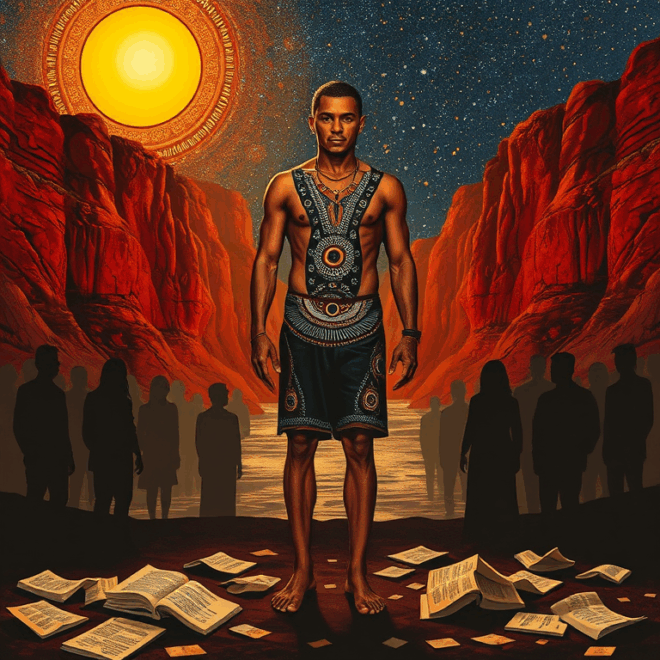

the colour of my skin –

the way sun has written story into my body,

an inheritance of earth running through every cell –

should not be a crime,

but it is.

I stand in a shop, ask for a glass

of cold water, feel the narrowed eyes,

the silent alarms,

the questions that greet my presence as accusation.

my culture – rock engravings,

laughter around a dusty fire,

language older than all the maps –

should not be a crime,

but it is.

They call our dances relics,

consign our words to museum cabinets,

try to rewrite history in textbooks

that pretend we just started existing in 1788.

my presence – here, breathing,

walking the streets of a land

that shaped the bones of my ancestors –

should not be a crime,

but it is.

To be Aboriginal is to be watched.

To be counted but rarely heard.

To sit in classrooms learning

how you are not truly part of the nation

you hold like a birthright

sharp in the palm of your hand.

my only crime

was to be born into the story of this country –

to carry a name echoing mountains,

to listen to the hum of the river,

to see the red ochre as memory and offering,

to survive in a society that looks away:

looks through you

and pretends not to see

the truth that sits on this continent,

older than monuments,

older than fences,

older than the English tongue –

We have been here

for sixty-five thousand years,

counting star seasons and songlines,

and you call us other,

you call us criminal

for wanting to belong

to what was always ours.

and yet:

we are still here,

unbroken,

each day an act of survival,

each word spoken

a reclaiming,

each breath –

a reminder:

we are not a crime,

we are not other,

we are

Country

in flesh and spirit,

refusing disappearance.