“Nihil ex historia discimus nisi quod ex historia nihil discimus”. Cicero

“Bella detesta matribus”. Horace

Introduction

The proposition that “every war is immoral though some have to be fought in the face of aggression” lies at the heart of humanity’s most enduring ethical quandaries. War, by definition, is a moral abomination: it unleashes indiscriminate violence, shatters lives, and erodes the very fabric of human dignity. Philosophers like Immanuel Kant argued that war violates the categorical imperative, treating individuals as means to geopolitical ends rather than ends in themselves. Just war theory, rooted in Augustine and Aquinas, posits criteria like just cause and proportionality, yet even “just” wars often devolve into atrocities, as seen in the civilian bombings of Dresden or Hiroshima. Ethically, war commodifies human suffering – psychic trauma, orphaned children, environmental devastation – for abstract gains like territory or power. In the nuclear age, this immorality escalates to existential risk, where escalation could annihilate billions, rendering any justification pyrrhic.

Yet, aggression sometimes demands response, as in resisting Nazi expansionism. The moral calculus weighs prevention of greater evil against war’s horrors, but this is fraught: Who defines aggression? What of pre-emptive strikes? In the Indo-Pacific, China’s assertiveness – evidenced by island-building and threats towards Taiwan – evokes such dilemmas for Australia. This essay examines whether strategic reasons (military, geographic, security imperatives) exist for Australia to engage in war with China, distinct from political motivations (ideology, alliances, domestic pressures). Ultimately, I argue that while aggression may theoretically necessitate defence, Australia’s case reveals no compelling strategic rationale; indeed, economic devastation, political isolation, strategic vulnerabilities, and profound ethical costs make war profoundly unwise. As of July 15, 2025, with Prime Minister Albanese meeting Xi Jinping amid US demands for war commitments, this tension is acute. Drawing on recent analyses, ethical frameworks, and historical contexts, we explore the multifaceted arguments surrounding this critical issue.

Historical Context: Australia’s Wars, Ethical Burdens, and China Relations

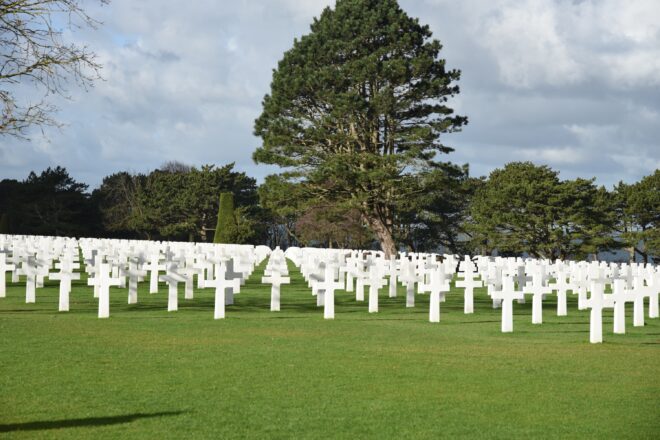

Australia’s military engagements underscore the immorality of war, even when framed as defensive. The catastrophic losses at Gallipoli during World War I, where approximately 8,000 Australians died in futile charges against entrenched machine gun positions, exemplify ethical ambiguity – these sacrifices served British imperial aims rather than responding to direct aggression. Ethically, this violated principles of proportionality: the negligible gains were vastly outweighed by the immense suffering incurred.

World War II’s Pacific campaign, initially framed as a necessary defence against Japanese aggression, similarly complicates the moral landscape. While the bombing of Darwin posed a direct threat to Australian sovereignty, the Allied firebombing of Tokyo, which resulted in the deaths of around 100,000 civilians, raises questions about the blurring lines between defender and aggressor. The Vietnam War, which resulted in the deaths of approximately 500 Australian soldiers and the extensive use of Agent Orange, highlights the political motivations that often drive military engagement rather than strategic necessity, leading to deep ethical reckonings over war crimes.

Relations with China further amplify these ethical considerations. Diplomatic recognition of China in 1972 fostered significant trade relations, yet Cold War tensions, characterised by China’s support for insurgencies in Southeast Asia, echoed the moral complexities seen in Vietnam. By the 2000s, economic ties had strengthened, with China absorbing 40% of Australian exports. However, the assertive militarisation of the South China Sea in the 2010s, deemed illegal by international law in a 2016 ruling, raised alarms and prompted calls for increased military preparedness.

Ethically, Australia’s response to China’s actions risks hypocrisy: condemning China’s “grey zone” tactics while hosting US military bases that may provoke further escalation. The 2023 Defence Review warns of growing contestation in the region, yet the ethics of war demand alternatives – diplomacy over destruction. Historical parallels abound; just as the appeasement of Japan prior to 1941 proved perilous, ignoring aggressive actions could invite future threats. However, overreaction, as demonstrated in the Iraq War, can lead to ethically questionable quagmires. For Australia, the ethical imperative favours restraint, given the disproportionate costs of war.

Current Geopolitical Landscape: Tensions, Alliances, and Ethical Imperatives

As of July 15, 2025, the geopolitical dynamics of the Indo-Pacific highlight the ethical perils of war amid the escalating US-China rivalry. China’s military buildup, characterised by nuclear expansion and aggressive military drills around Taiwan, constitutes a form of aggression. However, Australia’s involvement in any potential conflict risks moral complicity in further escalation. Recent incidents, including encounters between Chinese warships and Australian naval vessels, underscore the growing tensions and the ethical dilemmas inherent in military posturing.

These developments evoke pacifist arguments, reminiscent of Gandhi’s advocacy for non-violence and the peace testimonies of Quakers, urging nations to prioritise de-escalation to avert human suffering. However, the complexity of alliances complicates these ethical considerations. The AUKUS pact, which provides Australia with advanced submarines, ties Australia to US military strategies, potentially violating the principle of jus ad bellum (the right to go to war). The Quad alliance enhances regional security, yet US demands for Australian commitments regarding Taiwan, which were recently rebuffed by Defence Minister Conroy, underscore the political pressures that may overshadow strategic imperatives.

Prime Minister Albanese’s recent meeting with Xi Jinping emphasises trade and dialogue, signalling an ethical preference for diplomatic engagement over military confrontation. Economically, Australia’s dependence on China – approximately AUD 250 billion in trade – renders the prospect of war ethically indefensible, as sanctions could impoverish millions of Australians. Public sentiment, with 71% perceiving China as a threat, contrasts with the advocacy for peaceful alternatives by various commentators and analysts, highlighting the ethical complexities of public opinion and foreign policy.

Strategic Reasons for Australia to Go to War with China: A Critical Examination

Proponents of military action against China often cite strategic imperatives, yet these claims frequently overstate the necessity of war while ignoring ethical disproportionality. The defence of Sea Lines of Communication (SLOCs) is often highlighted, particularly the vulnerability of oil supply routes through the Malacca Strait, which are crucial to Australia’s energy security. However, it is essential to note that China’s military ambitions appear primarily regional rather than aimed at an outright invasion of Australia. Engaging in war would likely amplify existing vulnerabilities rather than mitigate them.

The argument for preventing Chinese hegemony is often framed around the potential fallout from a Chinese takeover of Taiwan, particularly concerning global semiconductor supply chains. Yet, Australia’s role in this scenario is peripheral; direct involvement may be deemed unethical in the absence of an imminent threat to Australian sovereignty. The notion of alliance deterrence, bolstered by the AUKUS agreement, raises further concerns about entrapment in US conflicts, which may not align with Australia’s national interests.

Concerns about resource security, particularly regarding China’s dominance in processing critical minerals, also surface in discussions about strategic imperatives. However, the devastation wrought by war on supply chains must be weighed against these concerns; the ethical and practical implications of military engagement render such strategic justifications insufficient.

Why War with China is Not in Australia’s Economic Interests

From an economic perspective, war with China would likely result in catastrophic consequences, far outweighing any purported strategic benefits. China is Australia’s largest trading partner, with exports to China sustaining approximately one in four Australian jobs. Modelling suggests that a conflict could potentially halve Australia’s GDP, while the economic fallout from sanctions – evidenced by the billions lost during the 2020 barley and wine sanctions – would be devastating for local industries.

The imposition of tariffs and other economic measures during previous US-China tensions has already demonstrated the vulnerability of the Australian economy to external shocks. The Reserve Bank of Australia has forecasted “dire” impacts from trade wars, underscoring the economic stakes involved. Efforts to diversify trade relationships have proven insufficient, as alternatives such as India cannot replace the volume of trade currently enjoyed with China. Ethically, the notion of impoverishing citizens to address hypothetical aggression violates utilitarian principles that prioritise maximising well-being and minimising harm.

Moreover, social media discussions reflect a growing awareness of the need for peaceful economic relations, with many commentators advocating for non-military solutions to tensions with China. Therefore, the economic interests of Australia strongly favour the pursuit of peace over the folly of war.

Why War with China is Not in Australia’s Political Interests

Politically, the ramifications of war with China could lead to isolation and division both domestically and internationally. Reports from July 2025 indicate US demands for commitments from Australia regarding military support for Taiwan. Such demands could fracture existing alliances if Australia were to refuse, while compliance would risk eroding national sovereignty and autonomy.

Prime Minister Albanese’s recent rebuff of US pressures highlights a prioritisation of independence in foreign policy. Domestically, the significant population of Chinese-Australians, constituting around 5% of the population, could face stigma and discrimination in the event of war, reminiscent of the internment of Japanese Australians during World War II. The electoral implications of such a conflict would likely disadvantage the government in diverse constituencies, raising ethical questions about the treatment of minority communities.

Regionally, Australia’s alignment with US military strategies could leave the nation isolated, particularly as ASEAN countries maintain a stance of neutrality regarding tensions between the US and China. Joining a US-led proxy war could alienate neighbouring countries, undermining Australia’s diplomatic standing in the region. Ethically, the warmongering that often characterises political discourse – exacerbated by media narratives – can manufacture public consent for military action, violating democratic principles of informed consent and public engagement.

Alternatives to military action, such as the peace declaration advocated by the Independent and Peaceful Australia Network (IPAN), are gaining traction, underscoring a growing political consensus in favour of diplomacy over war.

Why War with China is Not in Australia’s Strategic Interests

Strategically, the disadvantages of engaging in war with China are numerous. Australia’s military capabilities are currently undersized, and sustaining operations against a formidable Chinese missile arsenal is improbable. The geographical distance from Australia to potential conflict zones complicates logistical support, while the presence of US military bases may render Australia a target without guaranteeing a successful outcome.

The evolving nature of grey zone tactics – strategies that fall below the threshold of conventional warfare – presents a significant challenge. While Australia may seek to counter these tactics, engaging in war risks unnecessary escalation and further destabilisation. Importantly, there is currently no direct threat of invasion; China’s focus appears to be primarily on Taiwan, and engaging in military conflict over peripheral issues could be seen as disproportionate.

The recent acquisition of AUKUS submarines, while potentially enhancing Australia’s naval capabilities, will not be realised for several years, if at all, leaving interim vulnerabilities that could be exploited. Ethically, the notion of strategic overreach echoes the experiences of Vietnam, where disproportionate suffering was inflicted in pursuit of illusory security.

Expanding on the Moral and Ethical Aspects of War

The immorality of war transcends utilitarian calculations; it represents a profound ethical breach against humanity. From a deontological perspective, war defies the moral imperative of “thou shalt not kill,” treating lives as expendable commodities in geopolitical calculations. Consequentially, the outcomes of war – such as post-traumatic stress disorder, the displacement of populations, and environmental destruction – rarely justify the means employed to achieve military objectives.

In the context of the Australia-China relationship, the just cause for war remains dubious. While China’s actions may be characterised as aggressive, they do not constitute an existential threat to Australia. The principle of proportionality fails to hold; the risks associated with nuclear escalation and the potential for global devastation far outweigh any immediate benefits that might be gained from military engagement.

Civilian impacts of warfare – such as blockades that lead to starvation and bombings that result in orphaned children – are categorically unethical under the Geneva Conventions. The moral relativism that allows Australia to condemn China’s actions while overlooking the ethical implications of US military interventions presents a profound ethical inconsistency.

Even advocates of realism, such as former Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, caution against the devastating consequences of war. Ethically, Australia must prioritise peace, avoiding complicity in proxy conflicts that could lead to widespread suffering and loss of life.

Counterarguments and Alternatives

Pro-war advocates often cite deterrence as a primary justification for military action against China. However, viable alternatives exist that prioritise diplomacy and trade over military confrontation. Critics, including prominent political figures, have decried Australia’s perceived subservience to US interests, arguing for a more independent and nuanced foreign policy approach.

The absence of a direct invasion risk, particularly in the absence of provocation, further undermines the case for war. Engaging in military action without clear justification would be ethically and strategically indefensible.

Conclusion

Wars are inherently immoral – ethically bankrupt enterprises that produce suffering and destruction. Yet the temptation to respond to aggression can lead to calls for military action. In the case of Australia, no compelling strategic rationale justifies war with China; the potential for economic ruin, political division, strategic frailty, and profound ethical costs all point toward the imperative of restraint. As the year 2025 unfolds, with ongoing refusals of US demands for military commitments and increasing calls for peace, it is imperative that diplomacy and dialogue triumph over the spectre of war. The lessons of history remind us that the costs of conflict far exceed the potential gains, and the ethical imperative to pursue peace remains paramount.