Introduction

In the early 20th century, Milman Parry, an American classicist, fundamentally transformed our understanding of ancient epic poetry. His pioneering oral-formulaic theory challenged long-held assumptions about the composition and transmission of monumental works such as Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey. Rather than viewing these epics as the products of solitary literary geniuses who composed fixed texts, Parry demonstrated that they were the culmination of vibrant oral traditions sustained over generations. His theory posited that poets in pre-literate societies employed standardised phrases – known as “formulas” – and recurring thematic structures to compose and perform lengthy narratives spontaneously. These formulaic devices functioned as mnemonic tools, enabling the preservation and transmission of historical, cultural, and mythological knowledge with remarkable fidelity.

Parry’s ideas were not purely theoretical; they emerged from rigorous academic inquiry and compelling fieldwork. After earning his doctorate from the Sorbonne in 1928 with a thesis analysing Homeric epithets as formulaic elements, Parry embarked on groundbreaking research in Yugoslavia during the early 1930s. There, he and his assistant Albert Lord, documented living oral poets, or guslari, whose epic performances bore striking resemblance to the techniques Parry identified in ancient Greek bards. Their work revealed that oral poetry was a dynamic, creative act of composition-in-performance rather than mere rote memorisation. This empirical foundation not only validated Parry’s theory, but also broadened its applicability to oral traditions worldwide.

This post explores Milman Parry’s seminal findings from Yugoslavia and examines their relevance to Indigenous Australian oral traditions – specifically the songlines and Dreaming narratives that encode vast reservoirs of knowledge about history, geography, and law. Indigenous Australians, much like the Yugoslav guslari and Homeric poets, have relied on formulaic oral poetry to memorise and transmit vital cultural information across countless generations. While the advent of literacy often diminishes certain mnemonic skills, it does not negate the effectiveness or validity of oral traditions in pre-literate contexts. Through a comparative lens, this discussion underscores that oral poetry remains a sophisticated and reliable medium for preserving history, culture, and identity.

Milman Parry’s Life and Theoretical Contributions

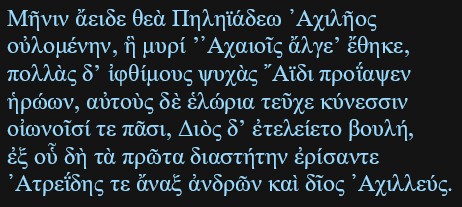

Milman Parry’s life, though tragically brief, was marked by profound scholarly achievements that reshaped classical studies and the broader understanding of oral literature. Born in 1902 in Oakland, California, Parry developed an early passion for the classics. After completing undergraduate studies at the University of California, Berkeley, he pursued advanced research at the Sorbonne in Paris. His doctoral thesis focused on Homeric noun-epithet formulas – recurrent descriptive phrases such as “swift-footed Achilles” or “rosy-fingered dawn.” Parry argued these were not ornamental literary flourishes, but practical compositional tools. Such formulas fulfilled metrical requirements, allowing oral poets to improvise verses during live performances while maintaining rhythm and coherence.

Upon returning to the United States, Parry joined Harvard University as an assistant professor. There, his scholarship deepened, influenced by earlier research from scholars like Matija Murko, who had studied South Slavic oral epic poetry. Parry identified key characteristics of oral composition: economy (using the most metrically efficient formula for a concept), extension (a repertoire of formulas fitting various metrical slots), and thrift (avoiding unnecessary repetition). These features empowered illiterate poets to create extensive epics by weaving together formulas and narrative themes – recurrent episodes such as assemblies, battles, or feasts – that acted as building blocks for storytelling.

Parry’s theory challenged prevailing Homeric criticism. The “Analyst” school dissected the epics into patchwork compilations by multiple authors, while the “Unitarian” school attributed them to a singular literary genius. Instead, Parry proposed a “traditional” model: the epics evolved organically through generations of oral singers, who adapted and re-performed inherited material. This reframed the question of authorship, focusing instead on the process of oral transmission and its capacity to preserve cultural memory.

Sadly, Parry’s promising career was cut short when he died in an accidental shooting in 1935 at the age of 33. Nevertheless, his assistant Albert Lord carried forward his legacy. Lord’s 1960 publication, The Singer of Tales, formalised the oral-formulaic theory and introduced the concept of “composition-in-performance” – the idea that oral poets create their works anew with each performance, using formulas and themes as mnemonic scaffolding. Drawing heavily on their joint fieldwork, Lord’s work cemented the empirical foundation of Parry’s insights.

Beyond classical studies, Parry’s contributions influenced anthropology, folklore, and linguistics by emphasising living oral traditions as analogs for ancient ones. His theory illuminated how pre-literate societies worldwide used formulaic devices as cognitive shortcuts, reducing the need for verbatim memorisation while ensuring narrative fidelity. This framework is essential for understanding oral histories as dynamic, adaptive, yet reliable transmissions of collective knowledge.

In sum, Milman Parry demystified oral poetry, revealing it as a sophisticated cultural technology that enabled pre-literate societies to maintain historical accuracy without writing – a foundational insight for comparative studies of oral traditions.

Fieldwork in Yugoslavia: Foundations of Theory and Tradition of South Slavic Oral Epic Poetry

Parry’s theoretical innovations gained compelling empirical support through his fieldwork in the Kingdom of Yugoslavia between 1933 and 1935. Accompanied by Albert Lord and local guide Nikola Vujnovi?, Parry sought living oral traditions to test his hypotheses about Homeric poetry. The South Slavic region was uniquely suited for this research. There, guslari – itinerant singers who accompanied themselves on the gusle, a single-stringed fiddle – performed lengthy heroic songs recounting historical and legendary events, including the Battle of Kosovo (1389) and conflicts with the Ottoman Empire. These performances echoed the scale, style, and themes of Homeric epics.

Over two expeditions, Parry and his team recorded over 12,500 texts comprising approximately 700,000 lines. Utilising aluminium phonograph discs and meticulous notes, they amassed the largest collection of South Slavic oral literature. The corpus included Serbo-Croatian epics as well as Albanian songs, reflecting a multilingual oral culture. Parry focused particularly on Muslim singers from regions such as Novi Pazar and Bijelo Polje, whose epics could span up to 13,000 lines – comparable in length to Homeric works – unlike the shorter Christian songs prevalent elsewhere.

This collection revealed the mechanics of oral composition in vivid detail. Singers like Avdo Me?edovi?, whom Parry famously dubbed the “Yugoslav Homer,” exhibited extraordinary memory and improvisational skill. Me?edovi?, an illiterate man from Bijelo Polje, could perform epics exceeding 12,000 lines, such as “The Wedding of Smailagi? Meho,” improvising within formulaic frameworks. Common formulas – phrases like “saddle the horse” or “mount the steed” – filled metrical slots in the decasyllabic line structure typical of South Slavic poetry, enabling rapid composition. Narrative themes – episodes such as “hero’s arming” or “council of war” – served as skeletal frameworks that singers elaborated with culturally shared details.

Parry’s experimental approach was innovative. He asked singers to repeat songs or create new compositions on unfamiliar topics, demonstrating performance variability without loss of essential content. Singers like Salih Ugljanin translated songs between Albanian and Bosnian, showcasing oral tradition’s linguistic flexibility. These findings confirmed that oral poetry was not rote memorisation but creative recomposition, with formulas functioning as mnemonic and compositional aids.

Moreover, guslari performances preserved historical knowledge. Songs recounted real events – Ottoman conquests, the Battle of Kosovo – blending fact and legend to serve as communal histories in a semi-literate society. These epics conveyed moral lessons, heroic ideals, and social commentary, reinforcing ethnic and national identities amid complex Balkan politics.

Parry also documented the social dimensions of oral tradition. Singers learned their craft through apprenticeship, absorbing formulas and themes from elders, ensuring intergenerational continuity. Performances took place in coffeehouses, weddings, and festivals, where audiences actively participated – requesting songs, correcting details – thus collectively safeguarding the tradition. Regional variations emerged: Muslim epics were more elaborate and formula-rich, influenced by Islamic storytelling, while Christian songs tended to be concise and focused on resistance narratives. Literacy’s impact was evident: literate singers sometimes fixed texts in writing, but authentic oral poets eschewed writing to preserve fluidity.

The South Slavic oral tradition, rooted in medieval history, preserved events from the 14th century onward. Epic cycles such as the Kosovo Cycle mythologised defeat as moral victory, while others recounted outlaw exploits (hajdu?ke pesme) or border warrior tales (krajiske pesme). Although epic poetry was predominantly male-dominated, women’s roles appeared in lyric songs. By the 1930s, modernisation threatened the tradition, making Parry’s recordings a crucial preservation effort.

Parry’s Yugoslav fieldwork conclusively demonstrated that oral poetry is a viable medium for preserving history. The region’s living oral tradition provided a “laboratory” to understand how pre-literate societies composed, transmitted, and adapted epic narratives – a model applicable to other cultures.

The Likely Transmission of Homeric Poetry Until the Advent of Writing

Parry’s findings from Yugoslavia shed light on how Homeric poetry was likely transmitted orally before writing became widespread in ancient Greece. The Iliad and Odyssey, conventionally dated to the 8th century BCE, originated in a pre-literate society recovering from the Bronze Age collapse (1200 BCE), which ended Mycenaean literacy (Linear B script). During the ensuing Dark Ages (ca. 1100–800 BCE), knowledge of events such as the Trojan War (1250 BCE) was preserved orally by bards, or aoidoi, who passed stories down through generations.

This oral transmission likely involved successive singers adapting and elaborating Mycenaean-era tales, incorporating contemporary Archaic Greek cultural elements. The persistence of formulaic epithets like “godlike Achilles” suggests continuity rooted in Indo-European oral traditions. The epics themselves exhibit stratification – Bronze Age material mingled with Iron Age customs – indicating evolutionary composition over centuries.

The Greek alphabet, adapted from the Phoenician script around 800 BCE, marked the introduction of writing. However, literacy was initially limited; early written texts may have served as performance aids rather than fixed literary works. By approximately 600 BCE, under the Athenian tyrant Peisistratus (550 BCE), a standardised version of Homeric epics was likely commissioned for public festivals such as the Panathenaia. This process probably involved dictation, which froze the fluid oral tradition into canonical texts.

Thus, Homeric poetry was orally transmitted for centuries, blending myth and history much like the Yugoslav epics Parry studied. The epics preserved cultural values of heroism, fate, and honour, demonstrating that pre-literate oral traditions could maintain historical narratives with notable accuracy.

Indigenous Australian Oral Traditions: Songlines and Dreaming as Poetic Sources of History

Indigenous Australian cultures represent some of the world’s oldest continuous oral traditions, spanning over 65,000 years. Central to these traditions are songlines (or Dreaming tracks) – complex networks of songs that map the landscape, history, and law. These poetic narratives are sung during journeys across the land, recounting the travels of Ancestral Beings during the Dreaming, a timeless creation era.

Songlines serve multiple intertwined functions. They operate as navigational maps encoding water sources, sacred sites, and territorial boundaries; they preserve historical records of migrations and significant events; and they embed moral and legal codes essential for social cohesion. For instance, the Seven Sisters songline stretches thousands of kilometres across deserts, linking disparate clans through shared verses about ancestral women fleeing a pursuer. This songline encodes astronomical knowledge and territorial rights. Another example, the Marlaloo songline, follows two serpents naming places, preserving ecological and cultural knowledge.

Transmission of these oral traditions occurs through initiation ceremonies, where elders teach youth through performance, ensuring verbatim accuracy for sacred elements while allowing adaptation for contemporary contexts. The poetry employs rhythm, repetition, and metaphor – formulaic devices akin to those identified by Parry – often utilising archaic or ceremonial languages distinct from everyday speech. Performances incorporate dance, visual art, and didgeridoo accompaniment, creating multimedia mnemonic systems.

The historical validity of songlines is striking. They preserve knowledge of Pleistocene-era geological events, such as sea-level rises following the last Ice Age (10,000–12,000 years ago), confirmed by scientific research. Stories recounting drowned lands around the Great Barrier Reef or Tasmania’s separation illustrate oral memory spanning millennia. Additionally, oral narratives document volcanic eruptions, meteor impacts, and climate fluctuations, blending empirical observation with spiritual cosmology. This longevity and accuracy parallel the Yugoslav and Homeric oral traditions, underscoring oral poetry’s capacity to encode verifiable history.

Aboriginal song poetry often features archaic language, alliteration, and parallelism, enhancing memorability and performance. Songlines function as “libraries” of cultural knowledge crisscrossing the continent, linking communities and sustaining social structures. Although colonisation severely threatened these traditions, contemporary revival efforts – including digital mapping and educational programs – aim to preserve and revitalise them.

Applying Parry’s Theory to Indigenous Australians and Comparisons to Other Indigenous Societies

Parry’s oral-formulaic theory applies compellingly to Indigenous Australian traditions. Songlines exhibit formulaic repetition – standardised phrases describing landscapes, actions, or ancestral deeds – that fit rhythmic and melodic patterns, facilitating composition and recall. Recurring themes such as “Ancestor’s journey” parallel Homeric narrative motifs, allowing performers to expand and adapt stories extemporaneously while maintaining coherence.

During my university studies in classics, I explored Parry’s work extensively, which deepened my appreciation for how formulaic structures reveal universal mechanisms underlying oral traditions – including those of Indigenous Australians. The parallels are striking: just as Yugoslav guslari and Homeric bards encoded history through communal performance supported by formulaic language, Aboriginal songlines function similarly. These oral practices validate the transmission of complex, historically grounded narratives in pre-literate societies.

Comparisons with other indigenous cultures reinforce the global efficacy of oral traditions. Native American groups like the Klamath preserve histories through myths recounting natural disasters, such as the formation of Crater Lake approximately 7,700 years ago. West African griots, akin to guslari, use epic poetry and kora music to transmit genealogies and histories spanning centuries, blending fact and moral instruction. Polynesian societies, including the Maori, maintain whakapapa (genealogies) and waiata (songs) as navigational and historical tools, preserving voyages and events from millennia past. Inuit throat singing and storytelling encode environmental knowledge and migratory histories adapted to Arctic conditions over thousands of years.

These examples highlight oral traditions’ shared features: communal reinforcement ensuring accuracy, formulaic language aiding memory, and adaptive performance preserving relevance. Unlike static written records, oral histories engage both performer and audience, fostering living, evolving cultural heritage. Despite threats from colonisation and modernisation, these traditions demonstrate remarkable resilience.

The Impact of Literacy on Oral Traditions

The advent of literacy profoundly transforms oral cultures. Writing externalises memory, reducing reliance on mnemonic devices such as formulas and diminishing improvisational composition. In pre-literate societies, orality fosters deep cognitive skills for memorisation and spontaneous creation; literacy shifts focus toward fixed texts and authored works.

However, this shift does not invalidate the historical reliability of oral traditions prior to writing. Indigenous Australian songlines, Homeric epics, and Yugoslav oral poetry all demonstrate that pre-literate societies successfully recorded history and cultural knowledge through formulaic oral poetry. Literacy may alter how traditions are transmitted and preserved, but it does not undermine oral poetry’s fundamental role in maintaining accurate historical narratives.

Conclusion

Milman Parry’s groundbreaking work in Yugoslavia, combined with insights into Homeric oral transmission and Indigenous Australian songlines, affirms the power and validity of oral poetry as a medium for recording history in pre-literate societies. The empirical evidence from South Slavic guslari performances provides a living model illuminating how ancient Greek epics were composed and transmitted. Indigenous Australian traditions, with their intricate songlines and Dreaming narratives, similarly encode vast bodies of knowledge through formulaic oral poetry.

While literacy introduces new modalities of preservation and may diminish certain mnemonic skills, it does not negate the sophisticated oral mechanisms developed over millennia. Oral traditions remain dynamic, adaptive, and reliable cultural repositories. Understanding and appreciating these practices enriches our comprehension of human history, cultural memory, and the diverse ways societies have preserved their identities and knowledge across time.

By examining Parry’s theory alongside Indigenous Australian oral practices and global indigenous parallels, we recognise oral poetry as a universal and enduring human strategy for cultural survival and historical transmission – one that continues to inspire scholarship and cultural revitalisation today.