“The picture of the world that’s presented to the public has only the remotest relation to reality. The truth of the matter is buried under edifice after edifice of lies upon lies”

Noam Chomsky

Introduction

The establishment of the State of Israel in 1948 is often portrayed in popular narratives as a heroic saga: a story of a persecuted people returning to their ancient homeland after centuries of exile, transforming barren deserts into thriving communities through sheer determination and ingenuity, and defending their nascent state against overwhelming odds. This narrative, rooted in Zionist ideology, emphasises themes of redemption, resilience, and moral righteousness, particularly in the shadow of the Holocaust. It casts Jewish settlers as pioneers reclaiming a biblical birthright, building kibbutzim and modern cities while facing hostility from neighbouring Arab states. However, a closer examination of historical events reveals a far more nuanced and contested process. The “Jewish takeover of Palestine,” as some frame it, involved not only aspiration and survival but also displacement, violence, and colonial dynamics that led to profound suffering for the indigenous Palestinian population. This essay explores the origins, developments, and consequences of this history, drawing on diverse perspectives to challenge the oversimplified heroic lens and highlight the human costs on all sides. By delving into the multifaceted layers of this conflict, including the role of international powers, economic strategies, and military actions, we can better understand how the establishment of Israel was shaped by both idealism and pragmatism, often at the expense of Palestinian rights and self-determination.

Origins of Zionism: Aspirations Amid Rising Tensions

Zionism emerged in the late 19th century as a response to escalating antisemitism in Europe, particularly in Eastern Europe where pogroms and discriminatory laws threatened Jewish communities. Theodor Herzl, often regarded as the father of modern political Zionism, published Der Judenstaat in 1896, arguing for a sovereign Jewish state as the only solution to the “Jewish Question.” Influenced by the Jewish Enlightenment (Haskalah) and broader European nationalism, Zionism sought to secularise and nationalise Jewish identity, promoting the “ingathering of exiles” through immigration to Palestine, a land with deep religious and historical significance for Jews. Herzl’s vision was not merely spiritual; it was a practical response to the failures of emancipation in Europe, where Jews faced exclusion despite promises of equality. Early groups like Hovevei Zion (“Lovers of Zion”) began organising settlements in Ottoman Palestine as early as the 1880s, with the First Aliyah bringing thousands of Jews fleeing persecution. These initial waves included idealistic socialists who established agricultural communes, laying the groundwork for a self-sustaining Jewish society.

From the outset, Zionism’s goals included establishing a demographic Jewish majority in Palestine, which necessitated land acquisition and settlement strategies that prioritised “maximum land and minimum Arabs.” This was not merely a romantic return but a calculated colonial endeavour, as Zionist leaders like Herzl envisioned a state modelled on European nation-building. For instance, Herzl’s diaries reveal negotiations with colonial powers, including proposals to displace local populations in a manner reminiscent of other settler projects. While Jewish settlers viewed this as a rightful reclamation, citing biblical ties and the absence of a sovereign Palestinian state under Ottoman rule, local Arab populations saw it as an encroachment. By the early 20th century, land purchases by organisations like the Jewish National Fund displaced Arab tenant farmers, fuelling resentment and early clashes. The Jewish National Fund, established in 1901, explicitly aimed to buy land for exclusive Jewish use, often evicting long-term Arab cultivators who held customary rights, but lacked formal titles under Ottoman law. This led to economic hardships for Palestinians, many of whom transitioned from farming to urban labour, exacerbating social tensions.

Critics, including some historians, characterise Zionism as a form of settler colonialism, where European Jews, backed by Western powers, imposed their presence on an indigenous society, mirroring patterns seen in other imperial contexts such as Algeria or South Africa. This perspective contrasts sharply with the heroic narrative of empty lands being revitalised, as Palestine under Ottoman rule was already home to a diverse population of over 600,000 Arabs, alongside a small Jewish minority of about 60,000. Ottoman censuses from the late 19th century show a vibrant society with agriculture, trade, and cultural exchanges, debunking claims of a “land without a people.” Moreover, early Zionist writings, such as those by Israel Zangwill, popularised slogans like “a land without a people for a people without a land,” which ignored the existing Arab majority and set the tone for future erasure of Palestinian presence.

The movement gained international legitimacy with the 1917 Balfour Declaration, in which Britain pledged support for a “national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine, despite the region’s 90% Arab majority. Issued amid World War I as Britain sought Jewish support against the Ottomans, this declaration ignored Arab aspirations for independence, setting the stage for future conflicts. Zionist leaders like Chaim Weizmann lobbied Chaim Weizmann lobbied effectively for this endorsement, leveraging networks in London and promising strategic benefits. However, it was viewed by Palestinians as a betrayal, especially after Britain’s earlier promises of Arab self-rule in the McMahon-Hussein Correspondence of 1915-1916, which encouraged Arab revolts against the Ottomans in exchange for independence. The Sykes-Picot Agreement of 1916 further divided the Middle East between Britain and France, treating Palestine as an international zone but ultimately placing it under British control. This web of conflicting promises highlighted the imperial machinations that prioritised European interests over local self-determination, sowing seeds of distrust that would erupt in later decades.

The British Mandate: Immigration, Separation, and Resistance

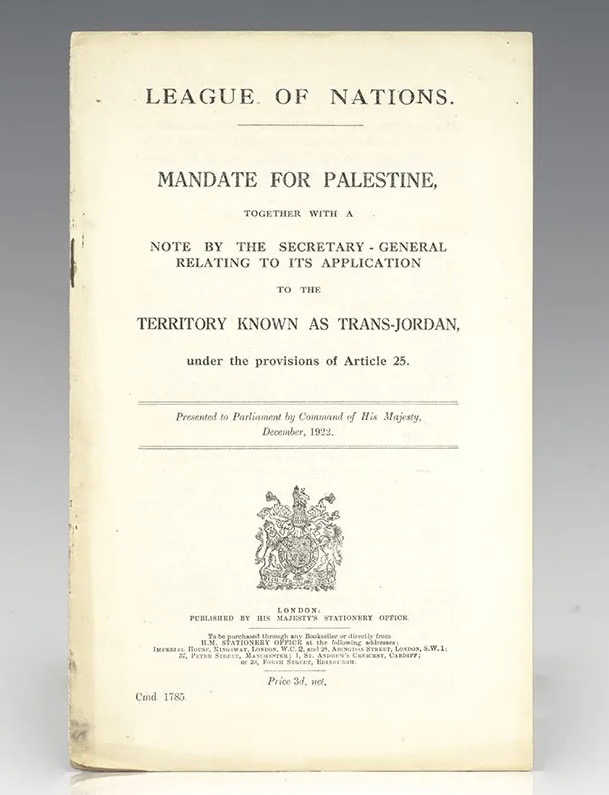

Following the Ottoman Empire’s collapse after World War I, Britain assumed control of Palestine under a League of Nations mandate in 1920, incorporating the Balfour Declaration’s commitments into its administration. This period saw waves of Jewish immigration, accelerated by Nazi persecution in the 1930s, with the Jewish population swelling from about 11% in 1922 to over 30% by 1947. Settlers established autonomous institutions, including the Histadrut labour federation, which controlled employment and welfare, and kibbutzim, collective farms that symbolised communal living and agricultural innovation. The heroic narrative celebrates this as innovative nation-building, with Jews draining swamps in the Jezreel Valley and cultivating land using modern techniques, symbolising renewal after centuries of diaspora. Stories of pioneers like those in the Second Aliyah (1904-1914) emphasise self-reliance and defence against Bedouin raids, portraying a narrative of triumph over adversity.

Yet, this era was marked by growing tensions and violence that revealed the Mandate’s inherent contradictions. Jewish land purchases, often facilitated by absentee landlords in Beirut or Cairo, evicted Arab peasants who had worked the land for generations, leading to economic dislocation and a sense of dispossession among Palestinians. By 1931, over 20,000 Arab families had been displaced, contributing to urbanisation and poverty in cities like Jaffa and Haifa. Zionist strategies emphasised economic separation, such as “Hebrew labour” policies that excluded Arabs from Jewish enterprises, exacerbating divisions and creating parallel economies. These policies, promoted by figures like David Ben-Gurion, aimed to build a Jewish-only infrastructure, but they alienated the Arab majority and fuelled nationalist sentiments.

Arab responses included riots in 1920, 1921, and 1929, resulting in hundreds of deaths on both sides, including the massacre of 67 Jews in Hebron during the 1929 disturbances. These events were not unprovoked; they stemmed from fears of Zionist expansion, as leaders like Ben-Gurion privately discussed “transferring” Arabs to ensure a Jewish majority. The 1929 riots, for example, were triggered by disputes over access to the Western Wall, but reflected deeper anxieties about land loss and demographic shifts. British inquiries, such as the Shaw Commission of 1929, acknowledged that Arab grievances were legitimate, recommending limits on immigration, but these were largely ignored under pressure from Zionist lobbies.

The 1936–1939 Arab Revolt represented a major uprising against British rule and Jewish immigration, involving strikes, sabotage, and guerrilla warfare across rural areas. Led by figures like Amin al-Husseini, the mufti of Jerusalem, the revolt demanded independence and an end to land sales. Britain responded with brutal repression, deploying tens of thousands of troops, imposing collective punishments like village demolitions, and collaborating with Jewish paramilitaries like the Haganah, resulting in over 5,000 Arab deaths and the dismantling of Palestinian leadership. Thousands were imprisoned or exiled, weakening Palestinian society structurally, while Zionists strengthened their military capabilities through the formation of elite units like the Palmach. The revolt’s suppression marked a turning point, as it fragmented Arab political organisation and allowed Zionists to consolidate control over key areas.

The Peel Commission of 1937 proposed partitioning Palestine, allocating a small Jewish state along the coast (about 20% of the land), which Zionists accepted as a foothold for expansion, but Arabs rejected outright, viewing it as an unjust division of their homeland. Britain’s 1939 White Paper, issued amid rising European tensions, limited Jewish immigration to 75,000 over five years and promised eventual independence, further alienating Zionists who saw it as a betrayal during the Holocaust. This led to insurgent attacks on British forces by groups like Irgun, including bombings and assassinations, escalating the Mandate into a three-way conflict.

Far from a heroic idyll, the Mandate period involved colonial favouritism, economic exploitation, and cycles of violence that foreshadowed greater tragedies. Britain’s inconsistent policies, balancing Zionist aspirations with Arab demands while prioritising imperial interests like oil routes and Suez Canal access, played a pivotal role, often at the expense of equitable resolution. By the end of the Mandate, Palestine was a powder keg, with deep divisions that international intervention failed to bridge.

Escalating to Partition and War: The 1947–1948 Turning Point

Post-World War II, the Holocaust’s horrors, claiming six million Jewish lives, intensified global sympathy for Zionism, with displaced persons camps in Europe swelling calls for a Jewish state. Survivors, many stateless and traumatised, sought refuge in Palestine, leading to organised illegal immigration (Aliyah Bet) operations like those aboard the Exodus ship in 1947, which dramatised Jewish plight and pressured Britain. Zionist groups, frustrated by immigration quotas, turned to terrorism against British targets, such as the Irgun’s bombing of the King David Hotel in Jerusalem in 1946, which killed 91 people, including Arabs, Jews, and British officials. This act, while condemned internationally, highlighted the desperation and militancy within Zionist ranks.

Britain, exhausted by postwar reconstruction and colonial retreats elsewhere, referred the Palestine issue to the United Nations in 1947. The UN Special Committee on Palestine (UNSCOP) recommended partition, and the General Assembly adopted Resolution 181 on November 29, 1947, proposing to divide Palestine: 55% for a Jewish state (despite Jews owning only 7% of the land and comprising 37% of the population), 43% for an Arab state, and Jerusalem internationalised. Zionists accepted the plan tactically, seeing it as a starting point for expansion, while Palestinians and Arab states rejected it as unjust, arguing it violated self-determination principles enshrined in the UN Charter. The partition sparked immediate civil war, with sporadic violence escalating into organised clashes.

The ensuing violence was chaotic and brutal, marked by atrocities on both sides. Zionist forces, better organised through the Haganah (precursor to the Israeli Defence Forces) and extremist groups like Irgun and Lehi, implemented Plan Dalet in March 1948, a military strategy to secure areas allocated to the Jewish state and beyond by conquering villages, destroying homes, and expelling inhabitants. This plan, while defensive in intent according to some interpretations, resulted in widespread displacement. Massacres, such as Deir Yassin on April 9, 1948, where over 100 Palestinian villagers were killed by Irgun and Lehi forces, triggered widespread panic and flight among Arabs. Reports of rape, looting, and mutilation amplified the terror, leading to the exodus of tens of thousands. Similar incidents occurred in Lydda and Ramle, where thousands were forcibly marched out in what Palestinians term the “Death March.”

By May 14, 1948, when David Ben-Gurion declared Israel’s independence, approximately 300,000 Palestinians had already been displaced. The declaration prompted invasion by Arab armies from Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Lebanon, and Iraq, marking the 1948 Arab-Israeli War. These forces, poorly coordinated and outnumbered by Zionist militias in key battles, aimed to prevent the partition but were hampered by internal rivalries and inferior armament. Israel’s victory, often hailed as a David-vs.-Goliath triumph, expanded its territory to 78% of Mandate Palestine, far beyond the UN plan. However, this came at immense cost: around 15,000 total deaths, including 6,000 Jews and 9,000 Arabs, with civilians bearing much of the brunt.

For Palestinians, it was the Nakba (“catastrophe”), with 700,000–750,000 expelled or fleeing, their villages, over 500 in total, destroyed or repopulated by Jewish immigrants, and properties confiscated under Israeli laws like the Absentee Property Law of 1950. Tactics included psychological warfare through loudspeaker announcements urging flight, looting to prevent return, and even biological methods, such as poisoning water sources in Acre to induce typhoid outbreaks. Historians like Benny Morris, in works like The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem, describe this as ethnic cleansing, inherent to Zionist aims of demographic control to ensure a Jewish majority state. While some Palestinians left voluntarily amid war chaos, the majority were driven out by force or fear, creating a refugee crisis that persists, with descendants now numbering over 5 million in camps across the region.

The war’s aftermath solidified Israel’s existence but at the price of ongoing enmity. Arab states absorbed refugees unevenly, with Jordan granting citizenship but others maintaining camps for political leverage. Israel’s narrative frames the war as existential survival, absorbing 700,000 Jewish refugees from Arab countries who faced expulsions and pogroms in retaliation. Yet, the asymmetry, Israel’s Law of Return welcoming any Jew while denying Palestinian return under UN Resolution 194, underscored the conflict’s inequities.

Criticisms of the Heroic Narrative: Settler Colonialism and Ongoing Legacies

The heroic portrayal of Jewish settlement often glosses over these realities, framing displacement as an unfortunate byproduct of war rather than a deliberate policy. Critics argue that Zionism embodies settler colonialism, where Jewish immigrants, supported by Western imperialism, supplanted the indigenous Palestinian population through land expropriation and violence. This framework, advanced by scholars like Patrick Wolfe, views Israel as a “structure, not an event,” where ongoing settlement in the West Bank continues the process of elimination of native presence. Parallels with European settlements in the Americas or Australia are drawn, noting how Zionists used biblical claims to justify dispossession, much like manifest destiny ideologies.

For instance, the “transfer” concept, discussed by Zionist leaders since the 1930s, aimed at removing Arabs, reflecting supremacist undertones in early writings. Ben-Gurion’s 1937 letter to his son Amos explicitly endorsed compulsory transfer if needed, revealing strategic intent beyond mere defence. Palestinian perspectives emphasise the Nakba as a foundational trauma, with refugees denied the right of return, leading to generational displacement and poverty. This asymmetry fuelled ongoing conflict, including the 1967 Six-Day War, where Israel occupied the West Bank, Gaza, and Sinai, displacing another 300,000 Palestinians and initiating settlements that now house over 700,000 Israelis in violation of international law.

Reports from organisations like Amnesty International and Human Rights Watch describe Israel’s policies as apartheid, enforcing domination over Palestinians in occupied territories through segregated roads, water allocation, and legal systems. Conversely, Israeli narratives stress self-defence against Arab aggression and the absorption of 850,000 Jewish refugees from Arab countries post-1948, arguing that the conflict was mutual and that Palestinians rejected peace offers, such as at Camp David in 2000. Yet, even within Israel, voices critique the heroic myth, as seen in documentaries like Israelism, which highlight the erasure of Palestinian suffering in education and media, fostering a generation unaware of the occupation’s realities. These internal debates, amplified by groups like Breaking the Silence, reveal fractures in the national narrative, where former soldiers testify to abuses in the territories.

The legacies extend beyond 1948, with the 1973 Yom Kippur War, intifadas in 1987 and 2000, and failed peace processes like Oslo in 1993, which promised autonomy but resulted in fragmented Palestinian areas surrounded by settlements. The Gaza blockade since 2007, following Hamas’s election, has created what critics call an “open-air prison,” with periodic wars causing thousands of deaths, predominantly civilians.

Zionist Propaganda in the West: Shaping Narratives and Silencing Dissent

A critical aspect of the heroic narrative’s persistence is the role of Zionist propaganda in Western media, politics, and education, which has systematically promoted pro-Israel perspectives while marginalising Palestinian voices. This propaganda machine, often coordinated by advocacy groups and lobbies, employs strategies to frame Israel as a beacon of democracy and innovation in a hostile region, while depicting Palestinians as inherently violent or obstructionist. In the West, particularly the United States and Europe, media coverage has exhibited consistent bias, emphasising Israeli suffering and security concerns over Palestinian grievances. For example, studies of U.S. outlets like The New York Times and CNN show disproportionate focus on Israeli casualties during conflicts, using emotive language for Israeli victims (e.g., “murdered”) while describing Palestinian deaths in passive terms (e.g., “died”). This bias is not accidental; it stems from editorial guidelines, source reliance on Israeli officials, and pressure from pro-Israel groups like AIPAC, which fund trips for journalists to Israel, shaping their reporting.

Zionist influencers and “hasbara” (Hebrew for “explanation”) campaigns play a key role, using social media and digital platforms to counter criticism. These efforts, funded by the Israeli government and diaspora organisations, involve coordinated messaging to portray Israel as under constant threat, often ignoring context like occupation or settlements. During the 2023-2024 Gaza war, Western media amplified unverified Israeli claims of Hamas atrocities while downplaying or delaying reports of Palestinian civilian deaths, contributing to what critics call “epistemic violence.” Journalists from CNN and BBC have spoken out about internal biases, revealing how stories critical of Israel face heavier scrutiny or suppression. This complicity extends to digital spaces, where algorithms on platforms like Meta censor pro-Palestinian content, labelling it as hate speech while allowing pro-Israel posts.

A particularly insidious tactic is conflating criticism of Israel with antisemitism, weaponising the term to silence dissent. The International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance (IHRA) definition, adopted by many Western governments, includes examples like denying Israel’s right to exist as potentially antisemitic, which critics argue stifles legitimate debate on Zionism as a political ideology. Adopted in 2016, the IHRA framework has been used to target academics, activists, and politicians; for instance, U.S. college campuses have seen investigations into pro-Palestinian groups under Title VI, equating anti-Zionism with discrimination. In 2023, the U.S. House passed the Antisemitism Awareness Act, incorporating IHRA, which opponents say threatens free speech by labelling criticism of Israeli policies as hate. Even Jewish critics, like those in Jewish Voice for Peace, face accusations of “self-hating” or antisemitism for opposing occupation. This conflation, as noted by UN experts, misuses antisemitism to shield Israel from accountability, diluting efforts against genuine Jew-hatred.

Zionist efforts to silence Palestinian voices extend beyond rhetoric to active suppression. In the U.S., groups like Canary Mission dox pro-Palestinian activists, blacklisting students and professionals, leading to job losses and harassment. In Europe, bans on Palestinian symbols like the keffiyeh or protests have escalated since 2023, with Germany raiding homes and cancelling events under “public safety” pretexts. France and the UK have dissolved pro-Palestinian organisations, labelling them as terrorist sympathisers, while social media giants censor content, removing posts about Gaza atrocities at higher rates than pro-Israel material. A UN report highlights this as a global threat to expression, with discriminatory policing of pro-Palestinian rallies. In academia, professors face firings for criticising Israel, and in media, Palestinian journalists are targeted, with over 100 killed in Gaza since 2023, often dismissed as “collateral damage.” These tactics create a “Palestine exception” to free speech, where advocacy for Palestinian rights is uniquely repressed in democratic societies. Despite this, resistance persists through alternative media, boycotts, and legal challenges, underscoring the resilience of Palestinian narratives.

Silencing Criticism in Australia: The Role of the Israel Lobby in Arts, Academia, and Media

In Australia, the Israel lobby, comprising organisations, influential donors, and political allies, has played a significant role in suppressing criticism of Israel across arts, academia, and media, often by conflating such criticism with antisemitism and exerting pressure through funding, lobbying, and public smear campaigns. This dynamic mirrors broader Western patterns but is amplified by Australia’s strong bipartisan support for Israel, limited media diversity, and a relatively small but vocal pro-Palestinian movement. The lobby’s influence has created an environment where voices challenging Israeli policies face professional repercussions, censorship, and marginalisation, raising concerns about free speech and democratic discourse.

In academia, Australian universities have increasingly capitulated to lobby pressures, particularly through the adoption of the IHRA definition of antisemitism, which has been used to equate anti-Zionism with Jew-hatred. For instance, at the University of Sydney, academics critical of Israel have been targeted, with professors facing investigations or disciplinary actions for exposing what they describe as falsehoods in Israeli narratives. The lobby, a major funder of universities, has lobbied for policies that suppress pro-Palestinian activities, such as encampments and seminars on Gaza. In early 2025, universities like those in New South Wales implemented codes of conduct that critics labelled as McCarthyist, aimed at shutting down dissent under the guise of combating racism. Education ministers have been pressured to intervene, with attacks on academic freedom conflating critiques of Zionism with antisemitism. Jewish academics, in particular, have reported subtle pressures to self-censor or risk career advancement, as seen in cases where scholars faced inquiries for supporting Palestinian solidarity. A parliamentary inquiry into antisemitism in late 2024 was criticised as a “Trojan horse” for the lobby, focusing on stifling campus activism rather than addressing genuine prejudice. These patterns of censorship, including disparate control techniques like surveillance and event cancellations, have been described as deeply disturbing, undermining the principles of open inquiry in higher education.

The arts sector in Australia has similarly witnessed attempts to silence artists who express solidarity with Palestinians or criticise Israeli actions. Pro-Israel politicians and lobby groups have attacked creatives, framing their work as divisive or hateful. In 2025, incidents involving the Venice Biennale highlighted this, where Australian artists faced backlash for statements on Gaza, leading to funding threats or exhibition withdrawals. Cultural institutions, reliant on private donations often tied to pro-Israel philanthropists, have responded to political pressures by censoring content, forcing artists to choose between career opportunities and moral stances. For example, during the Gaza conflict, many creatives reported self-censorship to avoid blacklisting, with organisations struggling to reconcile competing demands from donors and audiences. Public statements on the war have resulted in boycotts or smear campaigns, portraying artists as extremists. This climate has been exacerbated by government figures who label such expressions as threats to social cohesion, effectively weaponising anti-racism rhetoric to protect Israel from scrutiny.

Media in Australia presents perhaps the starkest example of lobby influence, dominated by outlets like the Murdoch Press, which has launched smear campaigns against groups like the Jewish Council of Australia for daring to criticize Israel. These campaigns often involve character assassination, accusing critics of malice or disloyalty, and have been backed by both major political parties. Mainstream coverage of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict is frequently biased, with limited balanced reporting on Palestinian suffering and a tendency to amplify Israeli perspectives. Journalists and commentators who deviate from this line face bullying or professional isolation, as the lobby monitors and responds aggressively to perceived anti-Israel narratives. The Australian media’s fear of debate on Israel’s treatment of Palestinians has been noted since at least 2021, with outlets avoiding in-depth coverage to evade accusations of bias. This silencing extends to alternative voices, where even Jewish anti-Zionist organisations are targeted, reinforcing a narrative that equates criticism with enmity. Overall, these efforts create a chilling effect, where public discourse is narrowed, and accountability for Israeli policies is evaded, prompting calls from human rights advocates for greater transparency and protection of free expression.

Conclusion: Toward a Truth-Seeking Understanding

The establishment of Israel was undoubtedly a remarkable achievement for a people emerging from genocide, symbolising hope and revival amid despair. Yet, it was not the unalloyed heroic process often depicted in Western discourse. It involved colonial alliances with powers like Britain, demographic engineering through immigration and expulsion, and violence that dispossessed hundreds of thousands of Palestinians, creating a refugee crisis that persists today with profound humanitarian implications. The ongoing occupation, settlements, and cycles of conflict, exemplified by the devastating 2023–2025 Gaza war, where tens of thousands have died, underscore how unresolved grievances fuel instability.

Recognising this complexity does not negate Jewish historical claims, the trauma of the Holocaust, or Israel’s right to security; rather, it fosters empathy for all involved, acknowledging Palestinian indigeneity and aspirations for statehood. As non-partisan scholars and activists advocate, truth-seeking requires dismantling propaganda, rejecting conflations of criticism with hate, and amplifying silenced voices. Only through such balanced dialogue, perhaps via renewed international mediation or grassroots reconciliation, can pathways to peace emerge, honouring the humanity on both sides rather than perpetuating myths of heroism or villainy. In a world where narratives shape policy, confronting these histories is essential for justice and coexistence.