Introduction

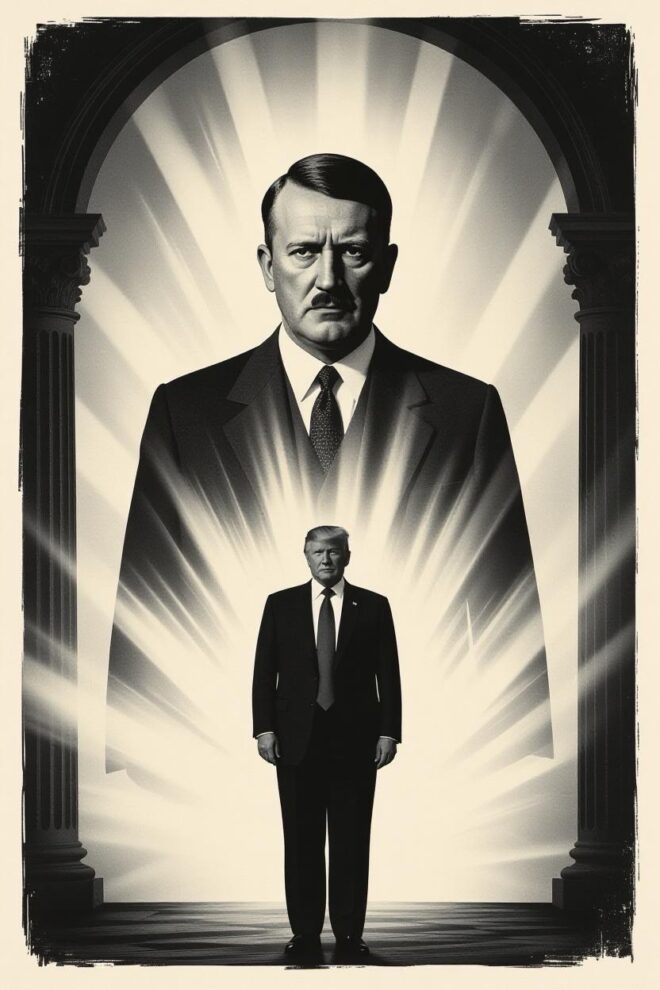

History sometimes produces years that crystallise a leader’s trajectory – moments in which apparent defeat becomes the forge of future power. In Adolf Hitler’s case, 1924 was that crucible: a year of trial, incarceration, and ideological consolidation that transformed a local agitator into a national figure. For Donald J. Trump, the year 2021 played a resonant, if not identical, role: a period following an attempted subversion of democratic processes that resulted in legal and social consequences, but also a reconfiguration of political identity and strategy. Comparing these years is not an exercise in facile equivalence. Rather, it is a focused examination of structural parallels – how failed coups and insurrections, the theatre of justice, enforced isolation (literal or figurative), the mobilisation of loyal followings, and media ecosystems can convert setback into momentum for those who traffic in grievance.

This essay draws out those parallels with attention to factual detail and to the differences that matter. The intent is not to conflate every trait of historical actors separated by time, culture, and context. Instead, it is to illuminate how democratic institutions, when stressed, can inadvertently provide demagogues with the materials they need to rewrite defeat as martyrdom, to transform courtroom podiums into campaign stages, and to turn sanction into a credential of authenticity for followers who see persecution as proof of righteousness. Such patterns offer consequential lessons for democratic resilience today.

The Catalyst of Crisis: Failed Coups and Electoral Insurrections

In November 1923 Adolf Hitler and his associates attempted to seize power in Munich through the Beer Hall Putsch. Borrowing imagination and aspiration from other European movements, the putsch combined theatricality with violence: a dramatic interruption at a civic meeting, a march through city streets, and an expectation that the army or sympathetic elites would rally. The attempt collapsed in a brief exchange of gunfire; several Nazis and police officers died, and Hitler was arrested shortly thereafter. The failure exposed organisational deficiencies and misreadings of broader public sentiment, yet it also produced national attention and a legal moment that Hitler would exploit.

A century later the United States witnessed a different, but analogously dramatic bid to overturn an electoral process. After the 2020 presidential election, President Trump and many of his allies alleged systemic fraud and irregularities. Those claims were subjected to judicial scrutiny in numerous courts; the majority of the resulting litigation did not find evidence sufficient to overturn results, and many lawsuits were dismissed. On January 6, 2021, a rally near the White House preceded a mass breach of the U.S. Capitol as Congress met to certify electoral votes. The breach halted the certification temporarily, resulted in deaths and injuries, and marked an acute moment of democratic peril.

Both episodes share a performative quality: the putsch and the January 6 events were public spectacles intended to intimidate institutions and create a narrative of resistance. Both involved the mobilization of followers prepared to use or threaten violence, and both were predicated on a claim that the normal course of politics had been corrupted – by a purported “November criminals” conspiracy in Weimar Germany and by allegations of a “stolen” election in the United States. Each leader in these episodes claimed authorship or inspiration even as they maintained a degree of physical distance from the most dangerous moments. The putschists marched; Hitler later framed the act as patriotic. On January 6, Trump’s speech and rhetoric energised supporters who then moved on the Capitol; the question of intent became the subject of intense legal and political debate.

The Spectacle of Justice: Trials as Platforms

A critical similarity is that failure did not equate to final marginalisation. In Germany, the authorities’ treatment of the putschists, including a relatively lenient sentence and the heavy publicity of the trial, allowed Hitler to amplify his message. In the U.S., the political consequences for participants and instigators have been real for many individuals, including arrests and prosecutions, and for the president there were political and social penalties: impeachment by the House and social media deplatforming. Yet neither outcome erased the underlying political forces: movements reconfigured, grievance narratives hardened, and a portion of the public continued to treat the events as vindication rather than refutation. In both contexts, what some hoped would be a decisive rebuke instead became a point of identity for adherents.

One of the most consequential after-effects of the Beer Hall Putsch was Hitler’s trial for treason in early 1924. The proceedings took place in Munich and were widely reported; the courtroom became a platform for Hitler’s rhetoric. The presiding judicial environment, in which certain officials evinced sympathy for nationalist causes, facilitated Hitler’s use of the trial as a venue for political theatre. He used his defence not to mitigate culpability but to justify his actions, articulate a sweeping worldview, and present himself as a defender of the nation. The sentence, five years in prison with release after a comparatively short time, was lenient by the standards of the charges and helped consolidate the image of Hitler as a wronged patriot.

In the United States, the post–January 6 political-legal moment also took the form of public adjudication, although primarily through political processes rather than criminal courts for the president himself. The House of Representatives impeached President Trump for “incitement of insurrection,” and the Senate trial that followed was televised and widely scrutinised. Videos from the Capitol, testimony from law enforcement, and extensive media coverage meant the impeachment became a national drama with competing narratives. The Senate did not convict; however, the trial gave political opponents an evidentiary and rhetorical basis to argue that the president’s rhetoric had tangible consequences.

There is a recurring dynamic in both cases: legal processes intended to punish or constrain produced publicity that the accused could convert into political capital. Trials and quasi-judicial proceedings are not only mechanisms for accountability; they are stages on which narratives are forged and audiences are mobilised. Hitler’s courtroom declarations became print material for distribution; in contemporary America, impeachment clips and trial coverage circulated in real-time across television and social platforms. Where institutions fail to present unequivocal moral clarity, whether through inconsistent enforcement, political allocation of discipline, or structural bias, the spectacle of justice can be reframed by the accused as proof of persecution.

Imprisonment, Exile, and Forced Recalibration

The period Hitler spent at Landsberg Prison following his conviction is often considered transformational. The relatively comfortable conditions compared to typical penal circumstances, the visits from key associates, and the time alone all enabled an inward turn that produced strategic recalibration. Hitler began dictating what would become Mein Kampf, an ideological tract that fused autobiography with programmatic outlines for race-based national renewal. This work codified ideas that would later be central to Nazi policy: racial conspiracy theories, the territorialist concept of Lebensraum, and a rejection of parliamentary democracy. Prisons for him became incubators for doctrine and organisation.

The post-January 6 experience for Donald Trump had its own form of exile: social media bans, removal from major platforms, and a curtailed official communications infrastructure after leaving office. This digital silencing did not produce a manifesto comparable to Mein Kampf, nor did it involve enforced solitude. It did, however, push communications into alternative venues and intensified the role of intermediaries, family members, media allies, and new platforms, in carrying the message. Deplatforming fragmented but did not erase the reach: messaging migrated to niche platforms, email solicitations, fundraising events, and sympathetic media outlets. Rather than constraining political influence, isolation in the digital and institutional sense encouraged a narrative of persecution and martyrdom among followers who read the sanctions as evidence of bias and conspiracy.

An important similarity is the use of enforced separation as a tool for reinvention. Hitler’s prison experience contributed to a strategic pivot from attempted coup to seeking power through political institutions, an electoral path shored up by paramilitary support. In the American case, the response to 2021 involved a doubling down on legal and political strategies to contest outcomes, an intensive fundraising apparatus, and continued cultivation of loyalty among party officials and voters. Both experiences show how periods of constraint can refine messaging, activate supporters, and generate a renewed strategic focus.

Contextual Conditions: Fragile Polities and Polarised Societies

Comparative analysis must account for context. Weimar Germany in the early 1920s was a state reeling from war, territorial loss, reparations pressure, and economic collapse. Hyperinflation had devastated savers, social trust was frayed, and paramilitary groups operated with relative impunity. Those conditions created a receptive environment for radical narratives that promised restoration and scapegoating.

The United States in 2021 was not Weimar; it was, however, a polity subjected to intense stressors. The COVID-19 pandemic had inflicted substantial mortality and economic dislocation. Political polarisation had deepened over several electoral cycles, with trust in institutions and media eroded among large constituencies. Economic dislocation and cultural anxieties provided fertile ground for populist narratives about elites, outsiders, and corrupt systems. Crucially, institutional differences matter: the American constitutional system disperses power across federal and state layers and includes entrenched legal protections. Yet distributive federalism can also diffuse accountability and create multiple points of leverage for actors seeking to contest outcomes, as seen in post-election challenges at the state level.

The point of comparison is not parity of crisis, but the functional consequence: when societies experience deep anxiety, fear, or dislocation, charismatic or populist figures can channel grievances into movements that reinterpret setbacks as proof of systemic betrayal. The grievances differ in scope and content – economic humiliation versus cultural and electoral grievances – but the political mechanics of mobilisation are comparable.

Followers, Loyalty, and the Cultivation of Victim Identity

Both historical moments reveal how movements sustain themselves through tight-knit loyal networks and the cultivation of victim identity. Hitler’s inner circle, figures such as Rudolf Hess and others, preserved and disseminated his ideas during imprisonment and beyond. These trusted lieutenants were instrumental in maintaining organisational continuity and in normalising the leader’s personal primacy: the Führerprinzip, which demanded absolute loyalty.

In the United States, the post-2020 movement around Trump involved family, media allies, party operatives, and grassroots activists who formed a resilient communications ecosystem. The construction of a martyr narrative – of an unfairly targeted leader and an embattled base fighting elite conspiracies, served to rationalise legal setbacks and to translate them into political potency. The spectacle of arrests or prosecutions of some participants, and the high-profile impeachment proceedings, were reframed by many as persecution against patriots, not as consequences for violence or legal breaches.

This shared feature, transforming sanction into a badge of honour, reinforces group boundaries and intensifies commitment. Where organisations institutionalise martyrdom, they often become less amenable to self-correction because admission of error would undermine the moral identity on which loyalty is predicated. That dynamic complicates prospects for de-escalation and reconciliation.

Media Ecosystems and the Propagation of Myth

In both eras the media environment played an essential role in amplifying narratives. Print press in the Weimar era included sympathetic organs that retransmitted Hitler’s statements and sanitised actions for constituencies predisposed to nationalist rhetoric. Pamphlets, speeches, and early broadcasting contributed to the diffusion of his views beyond Bavaria.

The contemporary information environment is vastly more complex and instantaneous, but operates on similar principles: amplification, selective framing, and echo chambers. Cable networks, talk radio, social media platforms, and newer alternative networks provided vectors for narratives that contested mainstream coverage and reinterpreted events. The post-January 6 ecosystem featured videos and analyses that circulated rapidly and unfiltered, as well as organised campaigns to push alternative interpretations about the causes of the violence and the legitimacy of the election results. Where mainstream outlets presented footage of violence and documented its consequences, sympathetic outlets often framed the same material as provoked or exaggerated, or spotlighted grievances rather than actions.

The result is not merely amplification of messages but the construction of competing realities. When large segments of a polity inhabit distinct fact-spheres, corrective mechanisms, fact-checking, court rulings, institutional clarifications, may fail to convince adherents who distrust the sources delivering them. That epistemic fragmentation enables leaders to sustain followings through claim-making that is impervious to external refutation.

From Setback to Strategy: Paths Back to Power

The strategic consequence of these dynamics is a twofold pathway: tactical adaptation and institutional re-entry. Hitler’s post-prison strategy abandoned immediate violent seizure in favour of building a political machine that could achieve power through elections while maintaining paramilitary capacity to intimidate and suppress opponents. The combination of legal approach and extra-legal threat proved effective in the longer arc.

In the American setting, the tactical repertoire after 2021 included litigation, pressure on election officials and state legislatures, ongoing media mobilisation, and electoral politics: supporting sympathetic candidates for key administrative roles (such as secretaries of state) and running for office again. Legal proceedings, impeachment, and deplatforming did not extinguish the political infrastructure; instead they catalysed a focused effort to transform grievance into organisational leverage. The emphasis on changing personnel and procedures in future elections is an example of converting perceived defeat into institutional avenues for influence.

Notably, the differences matter: the United States’ entrenched constitutional checks and norms provide certain defences, and the decentralised nature of electoral administration creates multiple points of contestation, both a safeguard and a vulnerability. The contrasting outcomes depend heavily on civic norms, the independence of institutions, and the willingness of elites to enforce rules even at political cost.

Lessons and Warnings

Comparing 1924 and 2021 is not an exercise in moral equivalence. Adolf Hitler’s ideology and actions culminated in genocide and global war; that cataclysmic moral and criminal landscape is unique and must not be relativized. At the same time, analytic comparison can reveal structural vulnerabilities that allowed an extremist movement to rebound from failure and eventually capture state power, vulnerabilities that democratic societies today must address.

Several lessons emerge:

- Publicity can empower as much as punish. Trials and public rebukes risk amplifying messages if they are not accompanied by clear, principled condemnation and consistent enforcement. Where legal or political accountability appears partial or politicised, sanctioned actors can convert scrutiny into spectacle.

- Isolation can be a crucible for strategy. Whether literal imprisonment or deplatforming, forced separation may enable recalibration and deepen ideological commitment rather than produce repentance. Policymakers should account for the unintended adaptive responses of targeted actors.

- Media ecosystems shape reality. Fragmented information environments permit the creation of alternative narratives that are resistant to correction. Robust public information strategies and platform accountability are necessary but not sufficient; civic education and norms of truth-telling are equally important.

- Institutional resilience matters. Courts, legislatures, law enforcement, and civil society must maintain independence and enforce rules even under political pressure. Where elites prefer expediency to principle, demagogues can exploit gaps to gain footholds.

- Cults of victimhood are durable. Narratives that cast leaders and followers as persecuted create moral shields against criticism and incentives supporters to double down when confronted by sanctions.

Conclusion

History is not a ledger of exact replicates, but a library of patterns. The year 1924 contributed to Adolf Hitler’s consolidation by converting failure into propaganda, giving him time to refine his program, and enabling loyalists to organise. The year 2021 produced a set of political dynamics that similarly allowed a disgraced and contested figure to reinterpret sanctions as persecution, to mobilise supporters, and to plot a path back into mainstream political contention. The parallels do not make the outcomes identical, but they do underscore a sobering truth: democracies are resilient only if their institutions, civic cultures, and media environments are robust enough to withstand not only overt coups but also subtler forms of subversion that exploit legal and informational gray areas.

This comparative analysis is a cautionary reflection, not a prediction. It presses civic actors, policymakers, and citizens to recognise how legal, communicative, and organisational incentives can turn setbacks into strategy. The safeguard against such transformations is not merely law enforcement but the cultivation of a political ecosystem in which truth, accountability, and pluralism are actively defended. Democracies that fail to do so risk providing the very conditions under which demagogues can transmute defeat into dominance.