The rock art of Arnhem Land, located in Australia’s Northern Territory, represents one of humanity’s most significant cultural achievements: a 50,000-year artistic tradition that encapsulates the spiritual, artistic, and ecological wisdom of Aboriginal peoples. This ancient gallery of paintings, etched into the caves, overhangs, and escarpments of the region, is the longest-running artistic “show” in history, continuing uninterrupted until the mid-20th century. The arrival of Czech ethnographer Karel Kupka in June 1956 marked a pivotal moment, signalling the decline of traditional rock art practices and heralding global recognition, notably by UNESCO, which acknowledged the art’s universal significance. This essay explores the historical and cultural significance of Arnhem Land’s rock art, the impact of mission influence and assimilation policies, Kupka’s critical role in bringing Aboriginal culture to the world, UNESCO’s recognition and multifaceted preservation initiatives, and the art’s enduring resonance, as experienced through contemporary journeys into the region’s sacred sites.

The Ancient Art of Arnhem Land: A 50,000-Year Legacy

Arnhem Land is home to one of the world’s oldest continuous artistic traditions. Its rock art, dating back at least 50,000 years, predates the cave paintings of Lascaux in France or Altamira in Spain, making it a cornerstone of human cultural history. Created by Aboriginal communities, this art is not merely decorative but a deep expression of the Dreaming – the cosmological framework that binds past, present, and future in the Aboriginal worldview. The paintings depict totemic animals such as kangaroos, fish, snakes, and barramundi, alongside mythological figures like mimi spirits, believed to inhabit the landscape and guide human affairs.

The rock art of Arnhem Land spans an astonishing temporal depth, with evidence suggesting human occupation and artistic activity beginning around 65,000 years ago in some sites, though the most securely dated artworks extend back to at least 28,000 years at locations like Gabarnmung. This cave, known in the Jawoyn language as “place of hole in the rock,” features intricate paintings and engravings that reflect early human habitation, with radiocarbon dating confirming its antiquity among Australia’s oldest sites. Discovered in 2006, Gabarnmung was still visited by Jawoyn people until as recently as the 1950s, highlighting how these sites remained integral to cultural practices long after their creation. The cave’s ceiling is adorned with layers of art, including abstract motifs and figurative representations, painted using natural pigments like ochre, charcoal, and clay. These materials, sourced from the surrounding landscape, underscore the deep connection between the artists and their environment.

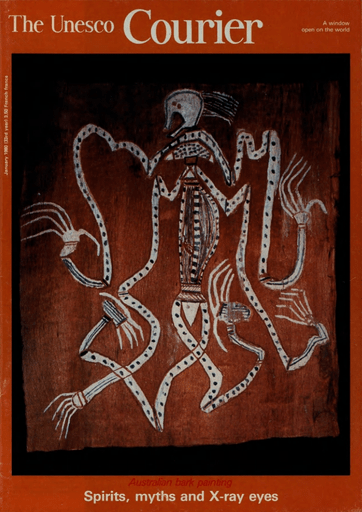

The art evolves through distinct styles over millennia, from early abstract motifs to the dynamic X-ray style, where internal organs and skeletal structures of animals and humans are vividly portrayed, symbolising a deep understanding of anatomy and spirituality. This X-ray technique, unique to the region, illustrates not just the external form but the essence or life force of the subjects, aligning with Aboriginal beliefs in the interconnectedness of all beings. In western Arnhem Land, the Dynamic Figures style showcases energetic human and animal forms in motion, often engaged in hunting or ceremonial activities. These figures, sometimes back-to-back, represent duality and power, a motif that persists in bark paintings and modern works, demonstrating stylistic continuity over 9,000 years.

Archaeological surveys in western Arnhem Land reveal over 100,000 rock art sites, forming one of the world’s largest assemblages. These sites, scattered across rocky escarpments and shelters, include depictions of extinct megafauna, such as the thylacine or Tasmanian tiger, hinting at environmental changes and human adaptation over time. For instance, paintings from the Maliwawa style, recently identified and dated to between 6,000 and 10,000 years ago, show large human figures and animals in red to mulberry hues, often shaded with stroked lines, providing glimpses into daily life, ceremonies, and human-animal relationships. A total of 572 Maliwawa paintings across 87 shelters underscore the style’s prevalence and its role in documenting a transitional period in Aboriginal history. These artworks depict scenes of people interacting with animals in ways that suggest companionship rather than mere hunting, such as humans holding onto the backs of kangaroos or emus, offering insights into ancient perceptions of the natural world.

The legacy extends beyond mere survival; it embodies ecological wisdom. Artworks often map resources, such as waterholes and food sources, serving as educational tools for generations. In the Wellington Range, rock art includes depictions of Indonesian praus (fishing vessels), evidencing pre-colonial contact with Macassan traders from the 16th century onward. These images, showing sails and crews, highlight cultural exchanges that influenced Aboriginal societies, including the introduction of new technologies and motifs into the art. Unlike Groote Eylandt, where Macassan influences are abundant, northwest Arnhem Land’s art suggests more limited but significant interactions, emphasising regional variations in contact history. Some motifs even portray Moluccan fighting craft, with triangular flags and prow adornments indicating marital status, suggesting that these vessels were not just for trade but also for raids or ceremonial voyages. This adds layers to our understanding of pre-European globalisation, where Aboriginal artists recorded foreign encounters as part of their historical narrative.

Sites like Ubirr, with paintings up to 40,000 years old, function as historical records, depicting game animals for magical increase or Dreaming beings for spiritual guidance. The art’s continuity until the mid-20th century demonstrates resilience, with bark paintings and modern works on paper echoing rock art styles, such as back-to-back figures symbolizing duality and power over 9,000 years. This unbroken chain underscores Arnhem Land’s role as a living archive of human creativity and adaptation. Moreover, recent analyses of 15,000-year-old panels reveal intentional compositions that reflect landscape history, with art placement shifting due to environmental changes like rising sea levels or climatic shifts. These panels, often layered over time, show how artists revisited sites, adding new meanings and adapting to evolving social and ecological contexts. The presence of painted hands, found in many shelters, is interpreted as symbols of survival and social cohesion, possibly created during rituals to strengthen group bonds amid challenges like resource scarcity or territorial disputes.

In addition to figurative art, abstract elements such as geometric patterns and stencils play a crucial role. Stencilled hands, tools, and boomerangs date back tens of thousands of years, serving as personal signatures or markers of presence. These stencils, made by blowing pigment over objects held against the rock, indicate individual participation in cultural events. The diversity of styles, from the early Panaramitee tradition of engravings to later polychrome paintings, reflects technological advancements and cultural exchanges. For example, the introduction of beeswax figures in some sites points to innovative techniques for creating three-dimensional effects on flat surfaces. Overall, the ancient art of Arnhem Land not only chronicles human history but also serves as a testament to the adaptability and ingenuity of its creators, who navigated vast environmental transformations while maintaining a spiritual dialogue with their surroundings.

The rock art also includes depictions of long-extinct creatures and animal-human relationships, as seen in the Maliwawa paintings, which feature bilbies, thylacines, and possibly dugongs alongside human figures. These images provide a remarkable glimpse into Indigenous life almost 10,000 years ago, showcasing a period when humans and animals were portrayed in harmonious interactions. The art’s temporal span covers the Pleistocene era, with evidence of early human settlement and adaptation to changing climates, from the Last Glacial Maximum to post-glacial warming. During colder periods, motifs focused on terrestrial animals, while later ones incorporated more marine life, mirroring rising sea levels that reshaped the coastline.

Furthermore, the art’s preservation in remote, pristine areas like the Arnhem Land Plateau has allowed for detailed study, revealing how Aboriginal peoples used these sites for both practical and ceremonial purposes. Shelters like Nawarla Gabarnmang, with its highly decorated surfaces, demonstrate a preference for certain colour combinations – red and white bichromes in Jawoyn areas – contrasting with the polychrome variety in northern regions. This regional variation highlights differences in beliefs, such as the emphasis on macropod Dreaming beings in the south versus fish and Rainbow Serpent motifs in the north. The art’s antiquity and volume make Arnhem Land a key region for understanding global rock art traditions, comparable to those in Europe or Africa but unique in its continuity and scale.

Historical and Cultural Significance

The historical significance of Arnhem Land’s rock art lies in its role as a chronicle of human experience, capturing migrations, environmental shifts, and social dynamics over tens of thousands of years. As one of the richest rock art regions globally, it offers insights into the Pleistocene era, with sites like those in the Arnhem Land Plateau featuring diverse styles from engravings to polychrome paintings. These artworks document the arrival of the first Australians, potentially as early as 65,000 years ago, through depictions of early tools, animals, and landscapes. The rock art assemblage in western Arnhem Land, in particular, is unparalleled, with thousands of sites displaying an astonishing array of imagery that spans from the Ice Age to recent contact periods.

Culturally, the art is intertwined with the Dreaming, where creation ancestors shaped the land and instilled laws governing life. Totemic figures, such as the Rainbow Serpent, appear in striped bands symbolising paths or boundaries, reflecting cosmological narratives. In western Arnhem Land, motifs like painted hands signify survival and social cohesion, possibly created during rituals to foster group unity amid environmental challenges. The art also records contact periods, with images of sailing vessels from Maluku Tenggara indicating martial or trading voyages, challenging notions of pre-colonial isolation. These depictions, such as the two similar watercraft at Awunbarna, show detailed features like pennants and prow adornments, linking them to eastern Indonesian origins and highlighting ethnic diversity in pre-European visitors.

Recent analyses reveal intentional site selection, with art placement shifting over time due to landscape changes, offering clues to social and economic transformations. For example, 15,000-year-old panels show evolving human activities, emphasising the art’s dynamic nature. In East Arnhem Land, Yol?u art ties to moieties (Dhuwa and Yirritja), governing kinship and ceremony, illustrating cultural complexity. The significance extends to contemporary identity, with artists like Yirawala innovating on traditional rarrk patterns to promote cultural respect. Contact rock art, depicting European influences, provides biographical insights into artists’ lives, enriching understandings of cross-cultural encounters. Overall, this art is a testament to Aboriginal resilience, serving as an irreplaceable history book.

To delve deeper, the historical layers of the rock art reveal how Aboriginal peoples engaged with their environment. During the Last Glacial Maximum, when sea levels were lower, artworks depict megafauna and vast inland seas, indicating a changing climate that forced adaptations in hunting and gathering. As the climate warmed, motifs shifted to include more marine life, reflecting the inundation of coastal areas. This environmental narrative is embedded in the art, where paintings of thylacines and diprotodons, extinct species, serve as memories of lost biodiversity. Culturally, the art functions as a mnemonic device, aiding in the oral transmission of knowledge across generations. Elders would use the sites to teach younger members about lore, kinship, and resource management, ensuring cultural continuity.

The cultural significance is also evident in the art’s role in ceremonies. Many sites were used for initiation rites, where young people learned sacred stories through visual storytelling. The Mimi spirits, slender humanoid figures, are believed to have taught humans how to paint, hunt, and live, embedding the art with educational and spiritual value. In some shelters, overlapping layers of art indicate repeated use over millennia, with newer paintings respecting older ones, symbolising reverence for ancestors. This palimpsest effect creates a dialogue between past and present, where each generation adds to the narrative without erasing the old.

Furthermore, the art’s historical value lies in its documentation of social structures. Depictions of human figures in groups suggest communal activities, such as dances or hunts, reflecting egalitarian societies with defined roles based on gender and age. Women’s contributions, often overlooked in early interpretations, are now recognised through motifs associated with gathering and child-rearing. Children’s involvement is also apparent, as seen in smaller hand stencils and simpler drawings, indicating that rock art was a family and community endeavour. In one case study from western Arnhem Land, a woman’s childhood memories of creating art highlight how these sites fostered learning and cultural transmission from a young age.

The integration of rock art with other cultural practices, such as song cycles (manikay) and dances (bunggul), amplifies its significance. Artists would paint while singing stories, linking visual and performative arts in a holistic expression of identity. This interconnectedness extends to modern Arnhem Land communities, where bark painting and contemporary media draw directly from rock art traditions, preserving rarrk (cross-hatching) patterns that encode clan ownership and spiritual authority. The historical and cultural depth of this art thus not only records the past but actively shapes present-day Aboriginal identity, resisting colonial erasure and asserting sovereignty over cultural heritage.

Contact rock art, in particular, offers a biographical perspective on cross-cultural encounters. Paintings of introduced animals like horses and cattle show a progression from initial awe to familiarity, with early depictions emphasising the unknown and later ones integrating them into local narratives. This evolution reflects Aboriginal agency in interpreting and incorporating foreign elements into their worldview. The art also challenges simplistic views of isolation, with pre-colonial motifs of Asian vessels demonstrating long-standing trade networks that brought tamarind trees, metal tools, and new artistic influences to the region.

In summary, the historical and cultural significance of Arnhem Land’s rock art lies in its ability to bridge deep time with contemporary life. It serves as a visual encyclopaedia of Aboriginal knowledge, encompassing ecology, spirituality, and social organisation. As a living tradition, it continues to inspire and educate, reminding us of the enduring strength of one of the world’s oldest cultures.

Impact of Mission Influence and Assimilation Policies

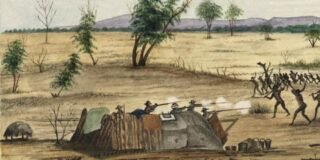

The arrival of European missions and government assimilation policies profoundly disrupted Arnhem Land’s traditional rock art practices, marking a shift from sacred continuity to cultural erosion. From the early 20th century, Methodist missions, such as those at Milingimbi and Yirrkala, introduced Christianity, education, and Western lifestyles, often suppressing Indigenous spiritual expressions. Missionaries viewed rock art as pagan, discouraging its creation and encouraging bark painting for commercial purposes, which diluted sacred motifs.

Assimilation policies, formalised in the 1950s and 1960s, aimed to integrate Aboriginal people into mainstream society, relocating communities to settlements and reserves. Under the 1961 Native Welfare Conference, these policies forced many from traditional lands, limiting access to sacred sites and interrupting knowledge transmission. In Arnhem Land, this led to a decline in rock art production by the mid-20th century, as younger generations were educated in missions and lost connections to ancestral practices.

Economic impacts were severe; mechanisation displaced unskilled Aboriginal labour, pushing many onto welfare and further eroding cultural activities. Legislation classified reserve residents as “assisted,” granting authorities power to relocate them, disrupting site custodianship. Vandalism, such as incidents near Gunbalanya, highlights ongoing threats from disconnection.

Despite this, some art adapted, incorporating mission influences like Christian themes, though at the cost of traditional purity. The policies fostered dependency but also spurred resistance, with communities like the Yol?u advocating for land rights and cultural preservation. Today, these impacts underscore the need for reconciliation, as many sites remain vulnerable to neglect.

Expanding on this, the mission influence began with the establishment of stations in the early 1900s, where Aboriginal people were encouraged to adopt European ways, including abandoning nomadic lifestyles for sedentary mission life. This shift meant less time spent at remote rock art sites, which were central to ceremonies and education. Missionaries often prohibited rituals associated with the art, labelling them as heathen, which led to a generational gap in knowledge. For instance, in western Arnhem Land, the suppression of sorcery and spirit figure depictions, key elements in rock art, forced artists to focus on more “acceptable” themes for sale to outsiders.

Assimilation policies exacerbated this by promoting the absorption of Aboriginal people into white society, often through forced removals and child separations. The Stolen Generations, where children were taken from families and placed in institutions, broke the chain of oral and visual tradition transmission. Many who returned as adults had lost fluency in languages and customs, making it hard to maintain rock art practices. In Arnhem Land, reserves like Maningrida became hubs where traditional art was commodified, but the sacred rock sites fell into disuse.

The policies also had environmental ramifications; relocation to coastal areas meant less maintenance of inland sites, leading to natural degradation. Vandalism increased as disconnected youth, influenced by Western culture, sometimes defaced sites. However, resistance emerged through art itself. Bark paintings, promoted by missions, became a medium for preserving stories, with artists like Paddy Compass Namadbara incorporating suppressed themes under the guidance of anthropologists.

Post-1960s land rights movements, sparked by events like the Yirrkala bark petitions, began reversing some damage. Communities reclaimed lands, reviving interest in rock sites. Yet, the legacy persists: many elders lament lost knowledge, and preservation efforts now involve reconnecting youth with heritage. The impact of missions and assimilation thus represents a dark chapter, but one from which Aboriginal resilience has emerged stronger.

Kupka’s Critical Role in Bringing Aboriginal Culture to the World

Karel Kupka’s arrival in Arnhem Land in June 1956 was transformative, bridging Aboriginal art with global audiences and documenting its decline amid modernisation. A Czech painter and anthropologist exiled in Paris, Kupka, influenced by surrealist André Breton, sought deep cultural knowledge. Landing at Milingimbi, he immersed himself in Yol?u communities, collecting bark paintings and sculptures from 1956 to 1964, a “golden age” of the medium.

Kupka was among the first to recognise individual Aboriginal artists’ talents, documenting provenances from “master-painters” across regions. His collections, now in museums, highlight continuity and innovation in ancestral traditions, showing the transposition of sacred art to the market. Books like “Dawn of Art” (1965) presented Aboriginal works as fine art, not ethnography, elevating their status.

His Catholic faith evolved through exposure, leading to works like “The Madonna of the Aborigines,” blending Indigenous and Christian motifs. Kupka’s efforts opened doors for recognition, influencing artists like Yirawala to share culture publicly. By the 1960s, his advocacy helped shift perceptions, paving the way for UNESCO acknowledgment. Kupka’s legacy endures in promoting Aboriginal art’s universal value.

To expand, Kupka’s journey began in 1950 with studies of museum collections in southeast Australia, but his Arnhem Land expeditions were pivotal. Surviving a plane crash en route, he arrived determined to capture the “spirit” of the art. At Milingimbi, he collaborated with local artists, learning from elders like Dhawarangulil and Dainganngan. His approach was respectful, noting individual styles and stories, unlike earlier collectors who treated art as artefacts.

Kupka’s collections, split between Basel, Paris, and Australian museums, total hundreds of pieces. He advocated for viewing bark paintings as contemporary art, influenced by Breton’s surrealist lens, which saw parallels with modern abstraction. His 1962 book “Un art à l’état brut” (Raw Art) featured Breton’s preface, introducing Aboriginal art to European intellectuals. This shifted global views, from ethnographic curios to artistic masterpieces.

In Arnhem Land, Kupka influenced locals; artists like Namadbara, suppressed by missions, revived spirit themes under his encouragement. Kupka’s documentation preserved knowledge during assimilation’s height, when traditions waned. His work inspired later collectors and anthropologists, contributing to the 1970s Aboriginal art boom. Today, projects like digital mapping of his collections reunite scattered pieces, honouring his role in cultural preservation.

UNESCO’s Recognition and Multifaceted Preservation Initiatives

UNESCO’s recognition of Arnhem Land’s rock art, primarily through Kakadu National Park’s dual World Heritage listing in 1981 for natural and cultural values, affirms its global significance. Kakadu, encompassing parts of Arnhem Land, features over 5,000 art sites dating back 20,000 years, representing humanity’s longest artistic record. This status protects sites like Ubirr and Nourlangie, with their panoramic views and interpretive signage.

Preservation initiatives involve collaborative efforts between Indigenous custodians, governments, and researchers. The Australian government’s National Heritage List includes sites like the Murujuga Cultural Landscape, emphasising protection under environmental laws. In Arnhem Land, projects like the Rock Art Australia initiative fund surveys and conservation, using novel methods to date and protect artworks. Community-led programs, such as those by the Jawoyn Association, monitor sites like Gabarnmung, integrating traditional knowledge with science.

Challenges include climate change, vandalism, and tourism impacts, addressed through restricted access and education. Digital archiving and 3D modelling preserve fragile sites, while Indigenous rangers patrol areas. These multifaceted approaches ensure the art’s survival, balancing preservation with cultural revitalisation.

Expanding, the 1981 listing highlighted Kakadu’s rock art as a key criterion, with sites like Burrungkuy (Nourlangie) offering walks through galleries depicting X-ray styles and Dreaming stories. UNESCO’s acknowledgment spurred funding for preservation, including the Kakadu Rock Art Project, which uses laser scanning to document sites threatened by weathering.

Indigenous-led initiatives are central; the Bininj/Mungguy people manage tours, ensuring respectful access. Programs like the Indigenous Protected Areas scheme cover Arnhem Land, where rangers remove graffiti and monitor erosion. Climate change poses risks, with increased rainfall accelerating pigment fading, prompting adaptive strategies like shelter reinforcements.

Collaborative research, such as the Archaeology of Rock Art in Western Arnhem Land project, applies analytical methods to understand antiquity and threats. Digital tools, including virtual reality tours, reduce physical impact while educating globally. These efforts not only safeguard the art but empower communities, fostering economic benefits through cultural tourism and reinforcing Aboriginal custodianship.

The Art’s Enduring Resonance: Contemporary Journeys into Sacred Sites

Contemporary journeys into Arnhem Land’s sacred sites reveal the rock art’s enduring resonance, blending ancient wisdom with modern experiences. Tours to Mount Borradaile offer glimpses of pristine galleries, where visitors encounter Dreamtime stories amid crocodiles and barramundi, feeling a temporal connection back to prehistoric times. Guides from Venture North Safaris interpret sites such as Injalak Hill, home to Yingarna, the Creation Mother, fostering respect for Bininj culture.

Personal narratives, like Nova Peris’s visit with former Prime Minister Tony Abbott, highlight truth-telling and cultural sharing, transcending politics. Modern interpretations, such as analyses of Maliwawa art, uncover human-animal bonds from 10,000 years ago, inspiring awe. Journeys emphasise ethical tourism, with permits required for Arnhem Land, ensuring benefits to communities. These experiences reaffirm the art’s vitality, connecting past and present.

To elaborate, tours like the Arnhemlander day trip cross Cahill’s Crossing into Arnhem Land, visiting Injalak Arts Centre where visitors watch artists weave pandanus baskets and paint. The Mikkinj Valley offers stunning escarpment views and billabongs teeming with wildlife. Luxury options, such as Outback Spirit’s Arnhem Land Wilderness Adventure, traverse from Gove to Darwin, incorporating rock art sites with Indigenous-guided walks.

Sacred sites like Ubirr provide sunset views over floodplains, where art depicts barramundi and turtles, evoking seasonal stories. Contemporary journeys often include cultural immersion, like learning didgeridoo or bush tucker. Ethical operators, such as Kakadu Cultural Tours, prioritise Indigenous ownership, with profits supporting communities.

These experiences highlight resilience; amid challenges like climate impacts, tours educate on preservation. Virtual journeys, using apps and online archives, extend access globally. Ultimately, these journeys foster reconciliation, allowing non-Indigenous people to appreciate the art’s ongoing relevance.

Conclusion

Arnhem Land’s rock art stands as a timeless testament to Aboriginal ingenuity and spirituality. From its ancient origins to modern preservation, it weaves a narrative of resilience amid change. As global appreciation grows, so does the imperative to safeguard this heritage for future generations.