Introduction

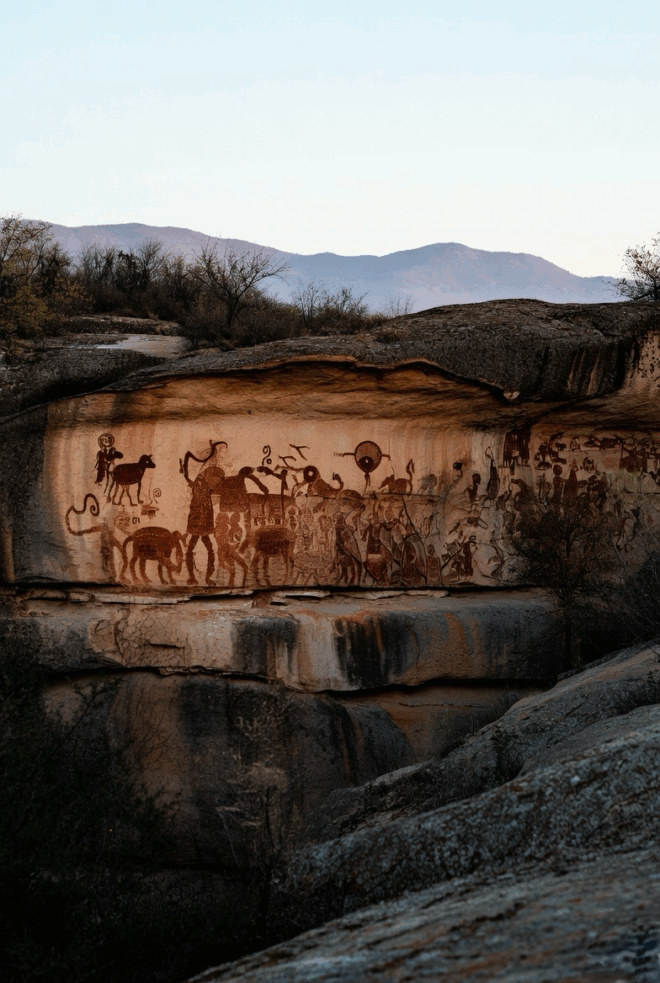

Rock art, encompassing a wide array of human-made markings on natural stone surfaces such as cave walls, rock shelters, and open-air boulders, represents one of the most enduring forms of cultural expression in human history. This ancient practice includes pictographs (paintings using pigments like ochre, charcoal, and mineral earths), petroglyphs (engravings or carvings into the rock), and other techniques such as stencilling and printing. Found on every continent inhabited by humans, rock art dates back tens of thousands of years and continues in some indigenous cultures to the present day. In societies without written language, it served as a vital medium for preserving and transmitting lore, encompassing myths, spiritual beliefs, and practical knowledge, and history, including accounts of environmental changes, migrations, and social events. Unlike ephemeral oral traditions, rock art provides a permanent visual archive that bridges generations, allowing descendants to reconnect with ancestral wisdom through symbolic imagery and narrative compositions.

The significance of rock art lies in its multifaceted role. It was not merely decorative; it often carried ritualistic, educational, and mnemonic purposes. For instance, motifs depicting animals, human figures, and abstract symbols could encode stories of creation, hunting strategies, or cosmological views, which were interpreted and retold during ceremonies or initiations. This transmission mechanism ensured cultural continuity, especially in hunter-gatherer and nomadic societies where mobility limited the use of portable artefacts. Archaeologists and anthropologists interpret these artworks through ethnographic analogies, comparing them to living indigenous practices, to unravel how they functioned as “libraries” of knowledge. In Australia, for example, Aboriginal rock art has been described as an archive of First Nations memories, histories, and relationships to the land, recording tales from the Dreamtime – a foundational period of creation in Aboriginal cosmology.

Globally, rock art spans from the Palaeolithic era (over 40,000 years ago) to more recent centuries, reflecting evolving human experiences. In Europe, Palaeolithic cave paintings capture the world of ice-age hunters; in Africa, San rock art documents shamanistic visions and colonial encounters; in the Americas, petroglyphs chronicle migrations and climatic shifts; and in Asia, rock shelters illustrate transitions from foraging to farming. Australia’s Aboriginal art, with its unbroken tradition stretching back at least 30,000 years, exemplifies how rock art adapts to convey ongoing cultural narratives. This essay explores rock art’s role in transmitting lore and history across generations, drawing on examples from multiple centuries and regions, with a particular focus on Australia. By examining techniques, motifs, and interpretations, it highlights how these ancient canvases continue to inform contemporary understandings of human heritage. Special attention will be given to Uluru, an iconic Australian site where rock art vividly embodies the transmission of Anangu lore, integrating it as a case study to deepen the discussion on Australian examples.

Prehistoric Rock Art: Foundations of Lore in the Palaeolithic Era

The earliest rock art emerges from the Palaeolithic period, roughly 40,000 to 10,000 years ago, when modern humans began creating symbolic representations that likely served to transmit essential knowledge in oral societies. These artworks, often hidden in deep caves or remote shelters, suggest a deliberate effort to preserve information for future generations, possibly through ritualistic viewing or storytelling sessions.

In Europe, the Upper Palaeolithic cave art of France and Spain provides iconic examples. The Chauvet Cave in France, discovered in 1994, contains paintings dating back over 30,000 years, featuring vivid depictions of lions, mammoths, rhinoceroses, and horses in dynamic poses. Techniques involved blowing pigments through tubes or using fingers to create outlines, with charcoal for black hues and ochre for reds and yellows. Interpretations suggest these images transmitted lore related to hunting magic or shamanism, beliefs that animals’ spirits could be invoked for successful hunts. The narrative quality, such as overlapping figures implying movement, may have helped elders teach younger generations about animal behaviours, migration patterns, and survival strategies. Similarly, Lascaux Cave, around 17,000 years old, includes over 600 animals and abstract signs, possibly symbolising seasonal cycles or mythological events. The “Hall of Bulls” depicts massive aurochs in procession, which could encode historical accounts of herd encounters, ensuring that knowledge of these now-extinct beasts persisted.

Moving to Asia, the cave art of Sulawesi, Indonesia, pushes the timeline further, with paintings dated to at least 45,000 years ago. These include hand stencils, created by blowing pigment around outstretched hands, and scenes of wild pigs and therianthropes (human-animal hybrids), suggesting transmission of animistic lore where humans and animals shared spiritual realms. In India, the Bhimbetka rock shelters, occupied from 30,000 years ago, show a sequence of motifs evolving over millennia. Early Palaeolithic layers feature large animals like bison and elephants, possibly teaching hunting techniques, while later Mesolithic additions depict communal dances and warfare, transmitting social histories and conflict resolutions.

Australia’s prehistoric rock art aligns with these global patterns but holds unique cultural depth, offering a wealth of examples that span tens of thousands of years. Aboriginal rock art, estimated at 30,000 to 50,000 years old in sites like the Kimberley region, uses ochre pigments integrated into rock surfaces, often enhanced by natural microbial activity for longevity. Motifs include Gwion Gwion figures, elegant human forms with headdresses, and spirit beings like Wandjina, cloud-like entities responsible for rain and fertility in Dreamtime lore. These images transmit creation stories: Wandjina are said to have painted themselves on rocks before entering the spirit world, instructing future generations on laws, taboos, and environmental stewardship. In Arnhem Land, X-ray style art reveals internal organs of animals, symbolising deep knowledge of anatomy gained through hunting, thus educating youth on butchering and respect for life.

Expanding on Australian examples, the Murujuga (Burrup Peninsula) in Western Australia boasts one of the largest concentrations of petroglyphs in the world, with engravings dating back potentially 40,000 years or more. These include depictions of human figures climbing, hunting scenes with boomerangs and spears, and extinct animals like the thylacine, which convey historical records of changing fauna and climate – from wetter periods with abundant wildlife to arid conditions. Such motifs served as educational tools, teaching descendants about ancestral hunting grounds and adaptation strategies. In Kakadu National Park, Northern Territory, sites like Ubirr and Nourlangie feature paintings from 20,000 years ago, showing barramundi fish, kangaroos, and human figures in dynamic poses. These artworks transmit lore of seasonal fishing and hunting practices, with overlapping layers indicating continuous use over millennia, allowing each generation to add or reinterpret elements during ceremonies.

Further south, in the Grampians (Gariwerd) National Park, Victoria, rock shelters contain art from around 22,000 years ago, including stencilled hands, animal tracks, and ceremonial figures. These sites, used by the Jardwadjali and Djab Wurrung peoples, encode stories of creation beings shaping the landscape, such as Bunjil the eagle creator, and practical knowledge like tool-making. In Queensland’s Carnarvon Gorge, engravings and stencils from 19,000 years ago depict nets, boomerangs, and spirit ancestors, transmitting kinship laws and territorial boundaries. Quinkan Country in Cape York Peninsula hosts rock art up to 15,000 years old, with Quinkan spirits – tall, thin figures – representing guardians of the land, used in initiation rites to pass down moral and survival lore.

These prehistoric examples illustrate rock art’s role as a generational bridge. Without writing, communities relied on these visuals to encode lore, spiritual, practical, and historical, ensuring survival in harsh environments. The permanence of rock allowed reinterpretation over time, adapting narratives to changing contexts.

African Rock Art: Shamanism and Historical Narratives Across Millennia

African rock art, spanning from over 75,000 years ago to the 19th century, offers profound insights into how indigenous peoples documented their worldviews and histories. Much of it is attributed to San (Bushmen) hunter-gatherers, whose art served as a medium for transmitting shamanistic lore and later, colonial-era events.

In South Africa, the Drakensberg Mountains host thousands of San paintings, dating from 3,000 years ago to the 1800s. Techniques involved fine brushes made from animal hair to apply polychrome pigments, creating intricate scenes of eland antelopes, human figures in trance dances, and therianthropes. The eland, a central motif, symbolises potency in San cosmology; shamans entered trance states to harness its power for healing or rain-making, and these images likely aided in teaching initiates about rituals. By depicting elongated bodies or bleeding noses (hallmarks of trance), the art transmitted experiential knowledge, allowing generations to visualise and replicate spiritual journeys.

Further north, in the Sahara Desert’s Tassili n’Ajjer plateau in Algeria, rock art from 12,000 to 7,000 years ago records a greener past with depictions of giraffes, elephants, and human herders. These large-scale paintings, using ochre and kaolin, may transmit historical lore of climatic shifts from savanna to desert, educating descendants on adaptation. In Namibia’s Apollo 11 Cave, slabs with animal figures date to 30,000 years ago, while Blombos Cave in South Africa has abstract engravings over 75,000 years old, possibly early symbolic systems for conveying group identities or territorial knowledge.

Later African rock art incorporates historical events, such as San depictions of European settlers with wagons and guns from the 19th century, blending traditional motifs with new realities. This evolution shows how rock art adapted to transmit narratives of contact, resistance, and change, preserving collective memory against cultural erosion.

In Australia, parallels exist with Aboriginal art’s adaptation. For instance, in the Pilbara region, petroglyphs on the Burrup Peninsula, spanning 30,000 years to the 1800s, include thylacines (extinct Tasmanian tigers) and later European ships, documenting faunal extinctions and colonial arrivals. These images transmit lore of environmental history and cultural encounters, similar to African examples. Additional Australian contact-era art in Kakadu includes 19th-century paintings of buffalo introduced by settlers and Macassan traders’ boats, recording trade histories and external influences on indigenous life.

African rock art thus exemplifies transmission through visual metaphors, linking spiritual lore with historical documentation, and influencing interpretations of similar art worldwide.

Rock Art in the Americas: Myths, Migrations, and Environmental Histories

Rock art in the Americas, from Alaska to Patagonia, dates from at least 15,000 years ago to post-contact periods, serving as repositories of indigenous lore and histories. Native American and South American peoples used it to record myths, astronomical observations, and societal changes.

In South America, Argentina’s Cueva de las Manos, 13,000 to 9,500 years old, features hundreds of hand stencils in red, black, and yellow pigments, created by blowing colour around hands pressed to the wall. Accompanying hunting scenes with guanacos transmit practical lore on group hunts and tool use, while the hands may symbolise communal identity or spiritual protection, passed down in rituals.

Brazil’s Serra da Capivara National Park contains paintings potentially 25,000 to 50,000 years old, depicting humans interacting with megafauna like giant sloths. These narratives challenge traditional migration theories, transmitting historical accounts of early peopling and environmental abundance.

In North America, petroglyphs in Nevada’s Winnemucca Lake, around 14,800 years old, feature abstract lines possibly representing water or celestial maps, aiding in transmitting navigational lore. The Chumash people of California created polychrome paintings in rock shelters, dating to 5,000 years ago, with motifs of sun, stars, and mythical beings, linked to astronomical knowledge for calendars and ceremonies.

Post-contact art, such as Plains Indian ledger art adaptations from rock traditions in the 19th century, depicts battles with settlers, preserving histories of resistance.

Australian comparisons include contact-era art in the Kimberley, showing Macassan traders’ boats from the 1700s, transmitting lore of external influences. This global pattern underscores rock art’s adaptability in documenting history. In Uluru-Kata Tjuta National Park, ancient Anangu rock art from thousands of years ago depicts Tjukurpa (Dreamtime) stories of creation ancestors like the Mala (rufous hare-wallaby people), teaching moral lessons and land care across generations.

Case Study: Uluru Rock Art and Anangu Lore

To further illustrate the depth of Australian rock art’s role in transmitting lore, we turn to Uluru, also known as Ayers Rock, an iconic sandstone monolith in Australia’s Northern Territory. Recognised as a UNESCO World Heritage Site for both its natural and cultural values, Uluru holds profound spiritual significance for the Anangu people, the traditional custodians comprising the Pitjantjatjara and Yankunytjatjara language groups. The Anangu view Uluru not merely as a geological formation but as a living cultural landscape imbued with Tjukurpa – the foundational law, stories, and spiritual beliefs that govern their existence. Tjukurpa, often translated as “Dreamtime” or “the Dreaming,” refers to the ancestral period when creator beings shaped the world, established moral codes, and left indelible marks on the land. These marks include physical features like caves, waterholes, and rock formations, as well as rock art that serves as a visual archive of lore and history.

Rock art at Uluru encompasses paintings, engravings, and drawings found in caves and shelters around the base of the rock. Created over tens of thousands of years, this art is evidence of continuous human occupation and cultural practice in the region, dating back at least 30,000 years. Unlike Western art forms, Anangu rock art is not decorative but functional: it educates, commemorates, and transmits sacred knowledge across generations. Motifs such as concentric circles, animal tracks, and figures encode complex narratives of creation, survival, and social responsibilities. Through guided tours, ceremonies, and oral storytelling, the Anangu continue to interpret and maintain these artworks, ensuring the vitality of their lore in the face of modern challenges like tourism and environmental change.

The creation of rock art at Uluru reflects the Anangu’s deep connection to the land and available resources. Paints are derived from natural minerals and organic materials, a practice that underscores the integration of art with the environment. Red, yellow, and orange hues come from ochres (tutu for red and untanu for yellow), which are ground on flat stones and mixed with water or animal fat to form a paste. White pigment is sourced from calcite or ash, while black is produced from charcoal, often from burnt desert oak (kurkara). These materials were highly valued and traded across vast distances, indicating the economic and cultural importance of art-making.

Techniques include finger painting, stencilling (blowing pigment around hands or objects), and drawing with sticks or brushes made from plant fibres or animal hair. The art is applied to cave walls and overhangs, where the sheltered environment protects it from erosion. However, dating the art is challenging; carbon dating reveals the age of the pigments or underlying rock but not necessarily when the painting occurred. Estimates suggest some artworks are thousands of years old, with layers of paintings overlaid on one another, symbolising ongoing use and reinterpretation. This layering is akin to a “classroom blackboard,” where elders illustrate lessons for initiates, erasing or adding as needed.

Conservation is a priority, as the art faces threats from natural elements like water runoff, dust, lichen, wasp nests, and animal activity, as well as human impacts such as touching or graffiti. Early tourism practices, like pouring water on paintings for better photographs, caused significant damage by dissolving pigments. Today, the Anangu Traditional Owners collaborate with park staff to document and protect around 80 rock art sites, using viewing platforms to minimise visitor impact. Visitors are encouraged to observe and photograph but not touch, respecting the art’s sacred nature.

Rock art sites are concentrated around the base of Uluru, particularly in caves and shelters that serve as ceremonial and educational spaces. Prominent locations include those along the Mala Walk and Kuniya Walk, leading to Mutitjulu Waterhole. These sites feature multiple layers of imagery, reflecting generations of use. For instance, caves near sacred men’s and women’s areas contain intricate designs carved or painted into the sandstone, used by elders to impart knowledge to younger generations.

Common motifs include geometric symbols like concentric circles, which can represent waterholes, campsites, or ceremonial grounds; animal tracks signifying totemic ancestors; and outlines of animals or human figures denoting creation beings. These symbols are polysemic, holding multiple meanings depending on context and the viewer’s level of initiation. For example, a circle might symbolise a specific site in a Tjukurpa story, such as a waterhole created by an ancestor, while also conveying lessons on resource management. Animal depictions, such as pythons or wallabies, link directly to ancestral narratives, reminding viewers of the beings’ journeys and the laws they established.

In the caves at Uluru’s base, ancient paintings adorn the walls, marking ceremonial sites and revealing creation stories. These artworks are part of Tjukuritja, the physical evidence of ancestral activities embedded in the land. Some sites are gender-specific: a cave resembling an open mouth is used by grandmothers to share women’s lore with granddaughters, while nearby intricate sandstone designs facilitate men’s teachings. Petroglyphs, engravings into the rock, also appear, telling stories of ancestors through countless incisions in cliffs and fissures.

The art’s motifs are not static; new paintings are still created during rituals, maintaining the tradition. This ongoing practice underscores the art’s role in cultural continuity, with symbols similar to those found across Central Australia, fostering a shared visual language among Aboriginal groups.

Uluru’s rock art is inextricably linked to Tjukurpa stories, which explain the world’s creation and provide guidelines for living. These narratives are embodied in the landscape, with rock art serving as mnemonic devices to recall and teach them. One prominent story is that of Kuniya and Liru. Kuniya, the woma python woman, travelled to Uluru carrying eggs, while Liru, the poisonous snake man, pursued her kin. Their confrontation at Mutitjulu Waterhole left marks in the stone – scars from spears and battles – that are visible today. The waterhole itself, a vital resource, symbolizes Kuniya’s victory and the ongoing presence of her spirit. Rock art along the Kuniya Walk illustrates elements of this lore, teaching respect for water sources and conflict resolution.

Another key narrative involves the Mala (hare-wallaby people), who arrived at Uluru for ceremonies but were disrupted by Wintalka (men from the west) and attacked by Kurpany, a devil-dog sent by the Luunju (kingfisher people). The chaos left physical evidence, such as boulders representing fallen Mala and caves used for initiations. Rock art in these areas depicts Mala figures and tracks, reinforcing lessons on hospitality, ceremony, and consequences of breaking law.

The story of the two tribes’ battle explains Uluru’s formation: ancestral spirits, distracted from a feast, sparked a war where leaders died, causing the earth to rise in grief. Rock outcroppings represent these spirits and touching them is believed to allow communication with Dreamtime ancestors. Grey lichen on the rock face symbolises smoke from fires set by the Bell-bird brothers in another tale, where they attempted revenge on lizard people but perished.

Broader Dreamtime motifs, like the Rainbow Serpent who shaped rivers and brought water, are reflected in wavy lines on Uluru representing python ancestors. These stories emphasise environmental stewardship: the serpent’s role in water cycles teaches about rain and floods, while frog ancestors like Murrujurlman highlight resource sharing.

Not all lore is shared publicly; some sites and meanings are restricted to initiated Anangu, preserving sacred knowledge. Over 40 sacred landmarks encircle Uluru, each tied to specific stories, acting as a map for survival – locating food, water, and shelter.

Rock art at Uluru functions as a generational conduit, complementing oral traditions, songs (Inma), dances, and ceremonies. Elders use the art to teach youth during initiations, pointing to motifs while recounting stories, ensuring cultural continuity. This “living classroom” approach allows reinterpretation, adapting lore to contemporary contexts while maintaining core principles.

Transmission extends beyond the Anangu through tourism: guided walks, like the Mala and Kuniya tours, share appropriate stories with visitors, fostering respect and understanding. Experiences at Ayers Rock Resort, such as dot-painting workshops, introduce symbols and narratives, bridging cultures. However, climbing Uluru – banned since 2019 – was seen as disrespectful, as it traverses sacred paths.

In a global context, Uluru’s art parallels other indigenous traditions, like Australian Aboriginal sites in Kakadu, where x-ray styles convey anatomy and respect for life. Yet, Uluru’s integration of art with landscape features makes it unique, embodying Tjukurpa as a holistic worldview.

Modern threats include climate change exacerbating erosion and tourism pressures. The Anangu advocate for protection, emphasising that Tjukurpa is not myth but living law. Digital documentation aids preservation, while community-led initiatives ensure lore’s transmission.

Uluru’s rock art lore inspires contemporary Aboriginal art movements, influencing canvas paintings and global exhibitions. It reminds us of humanity’s enduring need to connect with ancestors through visual storytelling.

Later Developments: Rock Art in Historical Contexts and Modern Interpretations

As societies transitioned to agriculture and complex polities, rock art continued, often blending with historical records. In Scandinavia, Bronze Age (3,000–500 BCE) petroglyphs at Tanum, Sweden, depict ships, warriors, and plowing scenes, transmitting lore of seafaring, warfare, and farming innovations.

In the Middle East, Negev Desert engravings from the Neolithic to Islamic periods record camel caravans and inscriptions, preserving trade histories.

Australia’s ongoing tradition, with art repainted in ceremonies, ensures active transmission. In Papunya, the 1970s art movement drew from rock motifs to convey Dreamtime stories amid cultural threats. In Nitmiluk National Park, rock art from 10,000 years ago to recent centuries includes depictions of Jawoyn creation beings and seasonal indicators. Injalak Hill in Arnhem Land features layered paintings spanning millennia, with recent additions documenting 20th-century events like World War II interactions. Cave Hill in South Australia, with Arrernte art, shows ancestral tracks and waterhole stories, maintained through songlines that link art to oral history.

Challenges include erosion and vandalism, but digital archiving aids preservation. Interpretations evolve with indigenous input, recognising art as living history.

Conclusion

Rock art stands as a testament to humanity’s ingenuity in transmitting lore and history without script. From Palaeolithic Europe to contemporary Australia, it encodes spiritual, practical, and historical knowledge, fostering cultural resilience. The integration of Uluru’s rich Anangu lore exemplifies how specific sites amplify global themes, bridging ancient narratives with modern stewardship. As we face global changes, these ancient voices remind us of our shared heritage, urging protection for future generations.