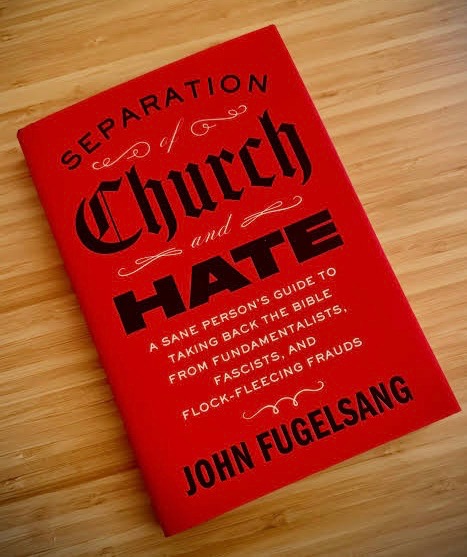

John Fugelsang’s Separation of Church and Hate: A Sane Person’s Guide to Taking Back the Bible from Fundamentalists, Fascists, and Flock-Fleecing Frauds arrives at a moment when the intersection of religion and politics in public life is both intensely scrutinised and dangerously exploited, and this book functions as a provocative, erudite, and often uproarious intervention in that contested space. Fugelsang, who brings to the project the layered perspectives of a stand-up comic, seasoned broadcaster, and the son of a former Catholic nun and a Franciscan brother, writes with the rare combination of scholarly familiarity with scripture, trenchant moral clarity, and a comedian’s instinct for timing and rhetorical flourish, all of which he deploys to argue that the forces commonly labelled Christian nationalists have perverted the teachings of Jesus in order to secure earthly power, consolidate privilege, and normalise exclusion and cruelty. The book stakes a bold claim that the true heart of Christian teaching aligns far more closely with mercy, solidarity, and radical hospitality than with the authoritarian, xenophobic, and hierarchical impulses that too often masquerade as doctrinal orthodoxy in contemporary political movements, and Fugelsang insists throughout that reclaiming the Bible from those who weaponise it is not simply a matter of theological debate, but an urgent cultural and ethical necessity.

From the outset, Fugelsang is unambiguous about his intended target, and he frames his project with an attention to nuance that will surprise readers who anticipate only comic derision; the vitriol directed at “flock-fleecing frauds” is tempered by an explicit refusal to conflate every believer with the architects of Christian nationalism, and the author repeatedly distinguishes between individuals who earnestly seek to live by the example of Jesus and those who manipulate religious language and authority to serve worldly ambitions. This rhetorical calibration is important because it allows Fugelsang to preserve both the moral seriousness of his critique and the strategic clarity of his appeal: he wants allies among believers, agnostics, and the irreligious alike, and he recognises that the persuasive force of his arguments will be diminished if they are dismissed as merely partisan or personal attacks. In making this concession explicit, Fugelsang advances a broader ethic of civic conversation that insists on fidelity to fact, to scripture, and to the historical record, and he invites readers to judge his conclusions not by his comic persona, but by the force of his evidence and the coherence of his moral reasoning.

A central strength of Separation of Church and Hate is the way it subverts the familiar rhetorical gambits used by many political and religious apologists to shield questionable policies from ethical scrutiny by invoking a supposedly monolithic biblical authority. Fugelsang approaches scripture not as an instrument for silencing dissent, but as a resource for critique, reading passages in context and reorienting the interpretive spotlight toward themes of liberation, care for the marginalised, and prophetic denunciation of unjust structures. Chapters such as “Thou Shalt Not Hate Feminists” serve not merely as rhetorical flourishes but as sustained hermeneutical challenges to the selective literalism that is often marshalled in defence of patriarchal social arrangements. In such sections, Fugelsang traces the roles that women play throughout the biblical narrative and emphasises the radical social implications of Jesus’s interactions with women, poor people, and outsiders, thereby undermining the claim that traditionalist gender hierarchies are biblically ordained. By doing so, he positions the Bible as a living text whose ethical centre inclines toward dignity and equality rather than toward the consolidation of male power.

Fugelsang’s method is notable for the way it combines rigorous engagement with scripture and history with the rhetorical agility of satire, and his use of humour is not merely ornamental but serves to disarm and to clarify. He understands that laughter can function as a moral instrument that exposes hypocrisy and reduces the aura of invulnerability that often surrounds institutional authority, and he uses it with surgical precision to puncture the inflated claims of those who profit from conflating religiosity with political entitlement. The humour is, at times, raw and laced with profanity, which may alienate certain readers, but which also reflects an aesthetic and rhetorical choice: Fugelsang refuses to sanitise the violence of the ideas he critiques, and his bluntness amplifies rather than diminishes the urgency of his indictment. Yet beneath the invective and the jokes there is sustained intellectual work, including citations of biblical passages, historical episodes, and contemporary political manoeuvres, that allows the book to function both as a popular polemic and as a practical resource for public conversation.

One of the book’s most consequential contributions lies in its practical orientation toward debate and public defence of progressive policy positions, in particular on culturally charged matters such as abortion, immigration, and LGBTQ rights. Instead of resorting to caricature or moral grandstanding, Fugelsang seeks to furnish readers with arguments that are both principled and accessible, drawing upon scripture to challenge appeals to divine mandate in political contexts where the stakes are human lives and freedoms. His approach to abortion demonstrates this stance well, as he refuses simplistic binaries and instead foregrounds an ethic of care and responsibility that prioritises the health, autonomy, and dignity of women. By insisting on the centrality of compassion and individual moral agency, he reframes the conversation in ways that make it more difficult for opponents to hide behind sectarian authority. Similarly, his discussion of immigration emphasises the prophetic tradition’s concern for the stranger and the alien, arguing that passages too often ignored or mistranslated by nationalist interpreters in fact counsel welcome and hospitality rather than exclusion.

Fugelsang’s critique of Christian nationalism is also sharpened by his historical sensibility, which he uses to show how religious rhetoric has been deployed across multiple epochs to legitimate oppression. He documents the ways in which political movements, far from being the authentic heirs of a pure and immutable Christian doctrine, frequently adopt a selective hermeneutic in service of the powerful, rewriting sacred texts to provide moral cover for racial hierarchies, economic inequality, and authoritarian governance. By situating contemporary examples within a broader historical pattern, Fugelsang not only undermines the notion that his targets represent a timeless and uncontested religious truth, but also invites readers to recognise patterns of moral corruption whenever religious institutions align themselves uncritically with state power. This historical framing is especially valuable because it discourages both temporal complacency and ahistorical nostalgia; it challenges readers to confront the moral dangers of unreflective allegiance, whether the allegiance takes the form of political partisanship or religious deference.

The book’s tonal range – from sharp satire to sober moral argument – would be less persuasive were it not for Fugelsang’s evident familiarity with the internal conversations and debates of religious communities, a familiarity that stems from both personal upbringing and professional engagement. He understands, for example, the pastoral anxieties that lead some believers to prioritise social cohesion or doctrinal certainty, and he treats those anxieties with a mixture of compassion and critique. This nuance allows him to spare “nice conservative Christians” the bulk of his ire, even as he lays waste to the rhetorical strategies of extremists who bend doctrine to serve wealth, status, and political domination. The distinction is important, because it invites readers who identify with mainstream religious commitments to see themselves as potential allies in resisting the uses of faith that degrade rather than ennoble public life. To put the point plainly, Fugelsang’s project is not an invitation to castigate religion wholesale; it is, rather, a clarion call to reclaim the moral and spiritual resources of the tradition for purposes that honour the least among us.

Throughout the book Fugelsang also reflects on the role of media and entertainment in amplifying the voices of religious demagogues, and he is unflinching in his critique of televangelism, punditry, and the market incentives that reward outrage and moral posturing. He documents how certain media ecosystems create feedback loops that inflate ideological extremes and reward performers who traffic in simplified certainties and righteous anger, which in turn serves to harden political divisions and to make compromise and dialogue more difficult. By exposing the commercial underpinnings of much contemporary religious rhetoric, Fugelsang encourages readers to take a more sceptical stance toward mediated religious authority and to seek out sources of moral instruction rooted in community, scholarship, and mutual accountability rather than in sensational headlines and click-driven outrage. This critique of media dynamics is especially salient in an era in which algorithmic amplification and performative religiosity can combine to produce powerful social and political consequences.

Fugelsang’s writing is not merely diagnostic; it is also prescriptive, and he offers practical advice for readers who wish to engage constructively with the religiously motivated arguments that animate public life. He encourages interlocutors to learn scripture themselves, or at least to consult serious scholarship, so that they are less likely to be outmanoeuvred in public debates by those who claim exclusive biblical literacy. He also advocates for forms of witness that prioritise vulnerability, story-telling, and sustained commitments to local institutions and mutual aid networks, arguing that moral persuasion is often more effective when it emerges from sustained practices of solidarity rather than from isolated acts of rhetorical bravado. This counsel is informed by a clear moral anthropology: Fugelsang believes that people change when they are known and cared for, not merely when they are argued into a new position, and his recommendations for grassroots organising and empathetic engagement reflect a conviction that political transformation requires both intellectual clarity and relational depth.

One of the book’s most compelling features is the way Fugelsang insists on the continuity between the prophetic critique of power in the biblical tradition and contemporary struggles for justice, and he reads scripture as a challenging mirror to modernity’s pretensions rather than as a refuge for reactionary politics. He attends carefully to texts that emphasise economic justice, the dignity of labour, and the obligations of communities to the poor, and he uses these texts to interrogate the moral legitimacy of economic arrangements that concentrate wealth while diminishing public supports for the vulnerable. This line of argument situates Fugelsang’s critique within a broader progressive theological trajectory that sees the demands of social solidarity and public provision as integral to a faithful reading of the New Testament, and it offers readers both a theological rationale and a practical framework for advocating policies that promote the common good.

It is important to acknowledge, as Fugelsang himself does on multiple occasions, that humour and ridicule can sometimes alienate the very audiences one hopes to persuade, and he is attentive to the ethical limits of satire. He recognises that effective persuasion requires a combination of moral clarity, intellectual humility, and rhetorical tact, and his critiques of his own rhetorical choices are as valuable as his critiques of contemporary Christian nationalism, because they model the kind of self-reflective political engagement that he advocates. In this regard, the book functions as both a manifesto and a meditation: it offers a spirited program for reclaiming religious discourse while also inviting readers to reflect on how to engage with neighbours and compatriots whose beliefs differ, sometimes radically, from their own. The result is a work that seeks to convert not through coercion, but through argument, narrative and the example of principled public life.

Readers who come to Separation of Church and Hate from a scholarly or theological background will find much to admire in Fugelsang’s attention to textual detail and historical context, and readers who approach the book primarily as a political or social critic will appreciate the clarity with which he links theological distortions to real-world harms. For those who approach the book with scepticism about the value of religion in public life, Fugelsang offers a corrective to the notion that faith is necessarily the ally of authoritarianism, demonstrating instead that religious language can be reclaimed to animate robust public commitments to human dignity and solidarity. Conversely, those who come from religious commitments will be challenged to consider whether their allegiances to political power have compromised their commitments to the moral core of their tradition, and Fugelsang’s work supplies both the evidence and the rhetorical means to initiate such difficult conversations.

If the book has a weakness, it may be that its bracing combination of satire and scholarly engagement occasionally strains the patience of readers who prefer purely academic discourse or, alternatively, readers who prefer unalloyed comedic denunciation. Some passages are likely to feel too clipped and biting for theological specialists seeking exhaustive exegesis, while others will feel weighty and dense to readers hoping for a lighter polemic. Yet this very tension points to the book’s ambition: Fugelsang is attempting something that few public intellectuals manage well, which is to bridge the gap between popular commentary and substantive theological reflection without sacrificing the integrity of either. The occasional unevenness is therefore an acceptable trade-off for a work that hopes to function both as a rallying cry and as a tool for public education.

In concluding, Fugelsang’s Separation of Church and Hate is a morally urgent, intellectually robust, and often delightfully scathing intervention into contemporary debates over the role of religion in public life. It is a book that refuses complacency and demands that readers think hard about the ethical stakes of religious language when it is pressed into service by political actors seeking power at the expense of the vulnerable. By reclaiming scripture as a source of radical compassion and social justice, and by exposing the rhetorical and institutional mechanisms through which Christian nationalism has sought to legitimate oppression, Fugelsang offers both a critique and a roadmap: a critique of how religious authority has been abused, and a roadmap for how religious communities and secular citizens might work together to restore truths that affirm dignity, equality, and mutual care. For anyone interested in the health of democratic discourse, the integrity of religious practice, or the pursuit of social justice rooted in ethical conviction, this book provides a sharp instrument and a compassionate guide. It calls on readers not merely to disagree with a set of politicised doctrines but to reclaim a tradition’s deepest commitments to serve those who are most in need, and in doing so it models the kind of courageous, honest, and humane civic engagement that democratic societies require.