Meta description: This long-form exploration examines the paradox whereby acts of brutality are justified in the name of preserving civilisation, surveying historical precedents, psychological mechanisms, legal frameworks, cultural and environmental costs, and potential paths toward accountability and restoration.

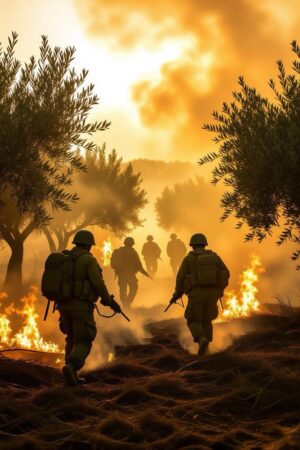

In the broad sweep of human history, the concept of civilisation has long been invoked as both an aspiration and a justification, a word intended to capture collective progress in law, arts, science, and morals while also serving as a banner under which states and societies claim legitimacy and moral superiority, and it is precisely this double-edged character of civilisation, with its capacity to inspire as well as to rationalise violence, that gives rise to the paradox at the heart of this essay: that in the name of preserving civilisation, its values, institutions, and purportedly enduring order, actors sometimes commit or condone acts of destruction and degradation that appear to belong more properly to the register of barbarism than to that of enlightened governance. This paradox is not merely theoretical; it is visible in concrete and troubling practices that recur across different conflicts and epochs, from the torching of libraries and the bombing of religious sites to the uprooting of centuries-old trees, the desecration of private belongings, the levelling of universities, the looting of cultural treasures and basic supplies, the criminalisation of children trying to survive, the use of disproportionate violence against youth, the public humiliation of captives, and the physical torture and degrading treatment of vulnerable individuals, all of which raise urgent questions about the ethical, legal and psychological foundations of modern societies that call themselves civilized.

The first of these practices, the deliberate destruction of libraries and archives, deserves careful attention not only because libraries serve as repositories of books and documents but also because they represent the collective memory of societies and are often the material substrate of identity and knowledge transmission, and when libraries are burned or plundered the loss cannot be measured merely in volumes destroyed but in stories erased, research trajectories interrupted, classrooms left bereft, and the long-term diminution of the intellectual resources available to future generations. Historically, the burning of libraries has been a recurrent tactic of conquest and cultural domination, whether in disputes over the origins of the famous Library of Alexandria or in the systematic book burnings staged in twentieth-century Europe as a means of eliminating dissenting ideas and codifying an exclusionary conception of culture; in more recent times, the looting and significant damage suffered by national libraries and archives during wartime, most notably the chaos that engulfed the National Library and Archives in Baghdad in 2003 following the U.S.-led invasion, when irreplaceable manuscripts and historical records were lost or destroyed, illustrate how the rhetoric of liberation and regime change can coexist with practices that obliterate the very traces of civilisational achievement that justify, at least rhetorically, the impulse to promote democracy and enlightenment. The psychological mechanism at work in the destruction of knowledge institutions is closely linked to processes of dehumanisation and narrative control: to deny a people their history and the means of recounting it is to make them easier to govern and to make alternative narratives more difficult to sustain, and the strategic loss of libraries therefore functions both as a means of immediate tactical advantage and as a long-term investment in the dominance of one story over others. Moreover, the consequences of such destruction are not only cultural, but socioeconomic and political; children and students deprived of educational materials are less likely to prosper economically, more susceptible to radicalisation in the absence of constructive alternatives, and more easily incorporated into cycles of dependency and political marginalisation, which in turn undermines stability and the democratic norms that are supposed to constitute the civilised order.

Equally troubling is the deliberate targeting or destruction of religious sites, an act that strikes at the deepest layers of communal identity, spiritual life, and architectural heritage, and which has recurred in conflicts where the removal or demolition of mosques, churches, temples, or other sacred places is rationalised as a necessary measure for achieving security, reasserting territorial claims, or correcting historical grievances. When religious monuments are torn down, whether in episodes such as the 1992 demolition of a disputed mosque in India that precipitated communal violence, or during the campaigns of ethnic cleansing in the Balkans in the 1990s when Ottoman-era mosques were systematically razed, or in the more recent and widely condemned destructions perpetrated by extremist groups in the Middle East, the immediate effect is to injure not only the religious sensibilities of communities but also the pluralist foundations upon which peaceful coexistence rests, and the intentional demolition of places of worship is recognised by international law and by many observers as a form of cultural violence that often presages or accompanies ethnic or sectarian cleansing. The justification sometimes offered for attacks on religious sites, that militants use them as hideouts or weapon caches, or that destroying them is a necessary price to pay in the pursuit of security, raises profound legal and moral questions about proportionality, necessity, and the proper limits of military action in populated areas, and it also risks a perverse strategic outcome: the creation of victims whose grievances are potent fuel for cycles of revenge and radicalisation, thereby undermining the very security objectives that the acts of destruction purportedly serve.

The burning or uprooting of ancient and economically vital trees, such as olive groves in many parts of the Mediterranean and the Levant, constitutes another form of violence that is both symbolic and pragmatic, operating as a means of economic warfare and cultural dispossession while also inflicting long-term environmental harm. Olive trees are not merely agricultural products; in many societies they are living repositories of lineage and memory, trees that have been tended by families across generations and that stand as tangible connections between people and place, and the purposeful destruction or confiscation of orchards and groves, whether through deliberate arson, clearance for settlement expansion, or punitive measures associated with counterinsurgency, severs those intergenerational bonds, impoverishes local economies, and accelerates ecological degradation. Historically, scorched-earth tactics have been employed to sap the will and capacity of adversaries; Sherman’s March to the sea during the American Civil War is often invoked as an archetype of total war in which civilian infrastructure was destroyed deliberately to break political resistance. However, the long-term consequences of such strategies are rarely confined to the duration of conflict, as degraded ecosystems, lost livelihoods, and demographic dislocation can create conditions that hinder post-conflict recovery, entrench poverty, and degrade prospects for reconciliation, thereby indicating that the supposed preservation of civilisation through such acts is deeply myopic because it sacrifices the very foundations, economic security, cultural continuity, ecological health, that allow civilisations to endure and flourish.

The appropriation and public display of personal belongings, including acts involving intimate apparel taken from displaced persons and subsequently displayed as trophies, exemplify another dimension of humiliation and dehumanisation that operates through the breach of privacy and the reduction of victims to objects of ridicule, and while such behaviour may be dismissed by some as crude indiscipline or wartime gallows humour, its social meaning is more profound: when soldiers or other actors treat the private possessions of displaced civilians as booty to be photographed and shared, they enact an extreme form of disrespect that undermines notions of human dignity, amplifies trauma among victims and their communities, and signals a collapse in the ethical constraints that ideally guide state actors and combatants. In a world connected by social media, the circulation of images depicting soldiers posing with civilian clothing or personal items magnifies harm by turning intimate humiliation into a public spectacle, and the effects upon communities already suffering loss are compounded by the knowledge that their private lives have been violated and their possessions instrumentalized for morale or propaganda, a practice that is widely condemnable under humanitarian principles which emphasise the protection of civilians and the preservation of their dignity even amid hostilities.

Closely related is the destruction of educational institutions, such as the levelling of universities or the conversion of academic spaces into battlefields or prisons; universities are not merely sites of instruction, but hubs of critical inquiry, innovation, social mobility, and cultural exchange, and their deliberate targeting has disproportionately damaging effects on the social capital of a society, disrupting research agendas, displacing scholars, curtailing the professional development of students, and stripping communities of the institutional capacities needed for reconstruction and governance in the aftermath of conflict. Historical precedents abound, from the medieval sacking of centres of learning to more recent attacks on campuses during civil wars, each illustrating how undermining education is tantamount to an attack on the future of a population, and while military planners sometimes invoke the tactical necessity of neutralising alleged armed elements who may hide among student populations, international humanitarian law seeks to protect educational facilities and the civilian population that relies on them, and the indiscriminate destruction of universities therefore becomes an ethically and legally fraught choice that often produces generational harm and exacerbates inequalities that contributed to instability in the first place.

Looting of cultural property, banks, art, jewellery and food supplies represents a multifaceted form of plunder that combines financial opportunism with efforts to erase identity and to deprive populations of the material means of survival, and the history of wartime looting, from the pillage accompanying the fall of empires to the large-scale theft of artworks and religious objects during colonial occupations, reveals how cultural expropriation functions both as a calculable economic gain for aggressors and as a symbolic attempt to appropriate or negate the history and status of the victim community. Modern international mechanisms, such as UNESCO conventions and efforts to repatriate cultural property, attest to the enduring significance of these artefacts for post-conflict recovery, but the looting of food and essential supplies escalates the moral stakes because it directly endangers civilian lives; food theft, the destruction of markets, and the targeting of humanitarian convoys are all acts that contravene basic principles of humanity and can constitute violations of international humanitarian law when they contribute to famine or systematic deprivation. Attempts to rationalise such looting as necessary retribution or unavoidable byproduct of war do not withstand ethical scrutiny when weighed against the duty to protect civilian life and nurture the cultural fabric that allows a society to identify, remember, and heal.

The arrest and criminalisation of children for acts that are often the product of poverty and survival, such as picking vegetables or gleaning fields, represents a particularly egregious inversion of the responsibilities that civilised societies claim to uphold, and when minors are detained, prosecuted, or subjected to abusive treatment for petty offences of subsistence, the resulting trauma deforms young lives and perpetuates cycles of marginalisation and resentment. The practice of targeting children in occupied territories or conflict zones with punitive law enforcement measures points to a broader pattern in which the apparatus of control and security is used to regulate and suppress ordinary livelihoods, and such enforcement is often uneven and discriminatory, contributing to the perception among affected communities that the legal order protects some citizens while instrumentalizing law to punish others. International human rights law emphasises the need for special protection for children, yet in practice the enforcement of those norms is frequently inconsistent, leaving minors vulnerable to detention, interrogation, and other forms of state-sanctioned pressure that contravene the ideals of a society that wishes to be judged as civilized.

When stone-throwing youths or demonstrators are met with lethal force, as has occurred in multiple contexts where asymmetrical force confronts improvised civil resistance, the proportionality of the security response becomes a central ethical and legal issue, and the shooting of unarmed or lightly armed protestors, many of them teenagers or even children, highlights the dangerous slide from law enforcement into militarised violence. The calculus that justifies the use of live ammunition against stone-throwers claims to be based on the protection of life and order, yet the optics and outcomes of such confrontations often produce the reverse: the creation of martyrs, the deepening of social cleavages, and the erosion of trust in state institutions, which in turn fuels cycles of retaliation and radicalisation. Law enforcement standards and international humanitarian law both emphasise the primacy of non-lethal force and de-escalation where possible, and when those standards are not adhered to, the resulting deaths and injuries become emblematic of a civilisation that has lost sight of its commitment to the preservation of life.

Public humiliation of captives, such as parading detainees in compromised states of undress, and the use of degrading treatment, whether in the form of staged photography, the desecration of personal dignity, or the employment of demeaning props, are practices that have surfaced in numerous scandals and abuses across conflicts, and the global shock that accompanied the release of images from places like Abu Ghraib in the early 2000s demonstrated that such acts are not merely interpersonal misconduct but indicative of systemic failures of oversight, training, and ethical restraint. Public humiliation serves multiple functions for perpetrators: it seeks to break the spirit of those paraded, to produce propaganda effects, and to erase the humanity of the detainees in the eyes of both captors and spectators, and it is precisely because these effects are so corrosive that international law and the norms of civilised conflict categorically condemn degrading and humiliating treatment of prisoners as tantamount to torture or cruel, inhuman, or degrading treatment.

Physical torture, whether in the form of blunt force trauma that breaks teeth, the insertion of foreign objects into bodily orifices, or other methods of severe physical and sexualised abuse, has long been recognised as a moral and legal boundary that civilised states and institutions must not cross, and yet allegations and documented instances of such practices persist in varied theatres of conflict and detention, often justified internally by appeals to necessity, intelligence gathering, or exceptional circumstances. Modern consensus, reflected in treaties such as the United Nations Convention against Torture and other international instruments, is that torture is never permissible, as it violates inalienable human dignity, produces unreliable information, corrodes the moral legitimacy of those who employ it, and often leaves both victims and societies with long-lasting psychological and social injuries. Beyond the immediate physical harm, torture disfigures the moral identity of institutions that engage in it, making it difficult for those institutions to claim a credible stake in upholding the rule of law and human rights.

The deliberate use of animals as instruments of violence against human beings, such as releasing aggressive dogs against detainees or vulnerable civilians, including those with disabilities, adds another grim layer to the catalogue of practices that degrade civilisation, because it compounds physical cruelty with the particular cruelty of delegating violence to animals trained to maul or terrify, thereby ensuring both bodily harm and the deep psychological terror that accompanies such assaults. Reports of these practices raise especially acute concerns when the victims are among the most vulnerable in society, people with disabilities, the elderly, or children, since the deliberate targeting of those least able to defend themselves undermines fundamental ethical principles about the protection of the weak and the duty of states and actors to exercise restraint and humanity even amid conflict or disorder.

Taken together, these examples illuminate the core paradox of civilisation: the very values that are supposed to distinguish civilised societies, respect for human dignity, the preservation of cultural heritage, the protection of the vulnerable, the rule of law, and the promotion of knowledge, are precisely the values that are most often compromised in the name of defending them, and the result is a perilous form of moral inversion in which ends are invoked to justify means that ultimately erode the ends themselves. The mechanisms that produce this inversion are not only strategic, but psychological: the process of dehumanisation, the dynamics of group identity and obedience to authority, the cognitive dissonance that allows perpetrators to label abhorrent acts as necessary, and the moral disengagement that follows when institutions fail to impose accountability all contribute to a context in which cruelty can appear instrumental and even rational. Social-psychological research shows how moral disengagement can be facilitated by euphemistic labelling, advantageous comparison, displacement of responsibility, diffusion of responsibility, dehumanisation, and attribution of blame to victims, and these cognitive manoeuvres are often reflexively available to those seeking to rationalise abuses in times of stress or conflict.

Legal frameworks exist to mediate some of these problems, but their effectiveness depends on enforcement, political will, and the impartiality of tribunals and mechanisms of accountability. International humanitarian law and human rights law provide norms and prohibitions, such as the Geneva Conventions’ protections for civilians and cultural property, the Hague Convention for the Protection of Cultural Property in the Event of Armed Conflict, the Convention against Torture, and various relevant United Nations resolutions, that, at least on paper, constrain the permissibility of attacks on libraries, religious sites, agricultural resources, educational institutions, and civilians more generally. Post-conflict instruments, including war crimes tribunals and mechanisms for the restitution of looted property and reparations to victims, offer avenues for redress, but the uneven application of justice, the politics of international relations, and the reluctance of powerful states and their allies to prosecute their own supporters frequently produce impunity, which in turn undermines the normative power of law and breeds resentment among those who feel they have no recourse but to continue resistance.

The cultural and environmental dimensions of these practices deserve special emphasis because they reveal the long-term costs of justifying brutality in the name of civilisation. The destruction of cultural heritage deprives future generations of the ability to reconstruct their own histories and erases the tangible links that connect people to place and to each other. The loss of biodiversity and the degradation of land, whether through scorched-earth campaigns or the uprooting of ancestral groves, reduces resilience to climate change precisely at a moment when environmental stability is essential to human security. Educational losses erode human capital and reduce the prospects for economic development and social reconstruction, and the psychological scars of humiliation and torture feed intergenerational trauma that can distort social relations for decades.

If the paradox of civilisation is to be resolved in a way that preserves genuinely civilised values, several broad imperatives should guide thinking and policy. First, the protection of cultural heritage, libraries, educational institutions, and agricultural resources must be elevated from rhetorical commitments to operational priorities in military doctrine, with clear rules of engagement, mandatory training in cultural property protection, and robust mechanisms for the rapid assessment and safeguarding of vulnerable sites during hostilities. Second, accountability mechanisms must be strengthened and insulated from geopolitical pressures to ensure that violations are investigated impartially and that perpetrators can be brought to justice, whether through domestic courts, international tribunals, or hybrid mechanisms, and this requires not only legal reforms but also sustained civic engagement and the strengthening of free and independent media that can document abuses and mobilise public opinion. Third, a renewed emphasis on nonviolent conflict resolution, mediation, and restorative justice approaches can reduce the perceived imperative to resort to brutal tactics in the name of short-term security, and investing in social and economic programs that address underlying grievances, land rights, access to education, livelihood opportunities, and political representation, reduces the fertile ground in which cycles of violence flourish. Fourth, the preservation of human dignity must be restored as a central normative precept of military and policing institutions, with strict prohibitions and training against humiliation, torture, and degrading treatment, and with transparent mechanisms for victims to obtain redress, rehabilitation, and compensation.

Finally, the role of ordinary citizens and civil society in resisting the normalisation of barbaric practices deserves emphasis, because the moral contours of a society are ultimately shaped by the conversations citizens have with one another about what is tolerable and what is not. When democracies and pluralistic societies are silent or indifferent to abuses committed in their name or by agents who claim to act for them, they abdicate a crucial responsibility; conversely, when journalists, scholars, human rights organisations, artists, and everyday citizens insist on the consistent application of principles and the protection of vulnerable populations, they bolster the resilience of civilised norms. This means cultivating empathy across lines of political and cultural division, amplifying the voices of those who have suffered, preserving and restoring what has been destroyed, and recognising that short-term security measures that rely on humiliation, cultural erasure, and physical violence ultimately undermine the credibility and sustainability of any claim to civilisation.

The paradox at the centre of this reflection is therefore not an intractable metaphysical contradiction but a moral test: the preservation of civilisation cannot be achieved by embracing the very tactics that civilisation is supposed to consign to the past, and if societies truly value life, dignity, knowledge, and pluralism, they must be prepared to defend those values even when it proves difficult to do so, even when the temptation to sacrifice them in the name of expediency appears pressing. To preserve libraries, mosques, trees, universities, artworks and food supplies, to protect children from criminalisation and bullets, to refuse public humiliation and torture, and to ensure that the vulnerable are cared for rather than abused requires an unambiguous recommitment to humane principles, reinforced by law, education, institutional design, and the persistent indignation of an informed public that refuses to allow the language of civilisation to become a cover for practices that belong to the realm of barbarism.

In sum, the preservation of civilisation is not a matter of defensive rhetoric or rhetorical triumphalism; it is a continuous practice of restraint, protection, and accountability, and societies that proclaim their civilised status must measure themselves by how faithfully they adhere to the protections they claim to uphold, particularly in the most testing moments when fear, anger, and the pressures of conflict make cruelty seem expedient. If the defence of civilisation requires us to embrace the destruction of the things that sustain human dignity and life, then it is time to ask whether that civilisation is worth preserving; if, however, we reaffirm a vision of civilisation that prizes the safeguarding of knowledge, heritage, livelihoods, and human persons even amid contestation, then we will have found a way to resolve the paradox not by opting for barbarity as a means to an end but by strengthening the very norms that make human flourishing possible. The mirror in which we must look is not one that reflects abstract superiority but one that shows whether our actions align with the principles we profess, and if they do not, then the work of repair, accountability, and cultural regeneration must begin without delay.