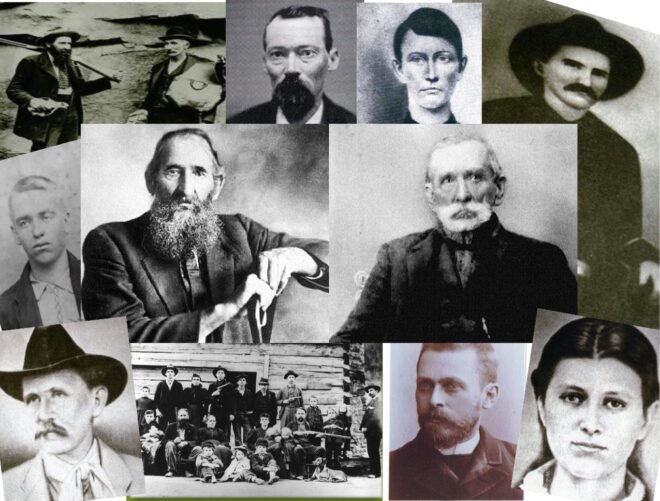

The names Hatfield and McCoy have come to signify something larger than the particulars of two families’ enmity; they stand as an archetype of how grievance begets grievance, how petty sparks can kindle long conflagrations, and how hatred, once entrenched, can feed on itself until it becomes almost independent of reason. The origin story – Civil War loyalties, a stolen hog in 1878, and the tragic romance between Johnse Hatfield and Roseanna McCoy – reads like the compressed narrative of countless human conflicts: small slights and big politics braided together until violence seems inevitable. By the time cabins were burned, men were tied to trees and killed, and the quarrel spilled into courtrooms, the feud had assumed a momentum of its own. But if one attends to the arc of that particular feud, another story emerges alongside the familiar narrative of blood and vengeance: the story of how hate transmutes from a reactive, understandable human emotion into a self-perpetuating social force carried forward by memory, ritual, and identity.

It is here – at the juncture where grievance becomes inheritance – that the Hatfields and McCoys teach a paradoxically hopeful lesson. Over the course of the twentieth century, the intensity of the feud diminished. Descendants, separated by time and context from the original provocations, found occasion to shake hands, to share stages on television, and to convert sites of violence into routes of remembrance and tourism. The transition from vendetta to folkloric brand suggests that hatred is neither inevitable nor ineradicable; it is conditioned, historically contingent, and therefore amenable to transformation. If hate can be neutralised, domesticated, or even commodified into a harmless curiosity, then the human community has resources – psychological, cultural, and institutional – with which to confront that darker side of our nature.

But to move from insight to action we must first understand the anatomy of hate: how it arises, how it persists, how it is transmitted across generations, and how it adapts to new media and political contexts. Only by unmasking the mechanisms that sustain cycles of enmity can we begin to devise effective remedies.

The genesis of hate is rarely monolithic. It often has proximate causes that are ordinary – economic insecurity, perceived disrespect, competition over scarce resources, contrasting identities stressed by conflict. When these proximate causes intersect with broader social or political fissures, they can be amplified. The Civil War context surrounding the Hatfield-McCoy conflict is illustrative: loyalties split, communities polarised, and postwar resentments simmered. Into such a combustible environment, a minor dispute – over a hog, a woman, or an insult – can serve as a catalyst. The immediate reaction is generally emotional and situationally rational: people protect family, defend honour, and retaliate to deter future injury. These responses are hardly exceptional; they are part of an evolved human repertoire for signalling resolve and deterring aggression.

What alters the calculus, however, is the move from immediate reaction to sustained campaign. When groups institutionalise grievance – through rituals, songs, memorials, and stories that valorise past wrongs – they reconstruct the past in a way that privileges injury and omits nuance. Memory becomes selective myth: the enemy is simplified; motives are compressed into moral categories; the moral universe is split into binary camps of villain and victim. Social identity theory helps explain this process. Individuals derive part of their self-concept from group membership; a threatened group identity elicits in-group cohesion and out-group hostility. Narratives of historical injustice provide a powerful glue, making present group identity dependent upon recollection of past wounds. Over time, the details of the original grievance lose salience; what remains is a scaffold of meaning in which hatred is justified by familial or collective identity itself.

Cognitive mechanisms compound these social dynamics. Confirmation bias leads people to seek and remember information that confirms their preexisting beliefs; motivated reasoning rationalises hostility as morally necessary; attributional biases interpret ambiguous actions by the out-group as malicious rather than accidental. Emotionally, the neuropsychology of threat and anger primes the fight response, narrowing cognitive bandwidth and increasing the likelihood of reactive violence. Once patterns of retaliatory violence begin, they create feedback loops. Each violent act is construed as proof of the other’s malevolence, legitimising further reprisals. The logic of reciprocity, twisted into a norm of vengeance, does the rest: retaliation demands retaliation, and escalation becomes a social imperative.

Equally important is the role of institutions and elites in either amplifying or mitigating hate. Leaders who cast conflicts in zero-sum terms, who mobilise grievances for political or economic gain, accelerate cycles of hostility. Conversely, institutions that provide impartial adjudication, that enforce the rule of law, or that create channels for peaceful contestation can dampen retaliatory spirals. In the Hatfield-McCoy era, weak and inconsistent legal authority in remote border regions allowed private retribution to substitute for public justice, enabling the feud to continue. By contrast, as modern institutions consolidated and as cultural norms shifted toward legal recourse and mediation, the feasibility and social acceptance of vendetta diminished.

Transmission across generations is the mechanism that most consistently turns ephemeral hatred into intergenerational inheritance. Children inherit not only the narrative of a wrong, but the practices that sustain it: tales told at the dinner table, commemorative rituals, songs and poems that sanctify prior violence. Because these narratives confer meaning and continuity, they can persist even when their original material bases vanish. The “why” of the feud becomes irrelevant; the feud itself becomes an identity marker. In communities where economic and social mobility are limited, where external contact is scarce, and where myths of honour and retribution are culturally reinforced, the stabilising factors that would ordinarily attenuate hatred are absent. There, enmity is more likely to calcify into social fact.

Modern life, however, has expanded the modes of transmission and altered the incentives surrounding hate. Social media, for example, accelerates the spread of grievance narratives by enabling rapid circulation of emotionally charged content. Algorithmic amplification privileges content that provokes engagement – often outrage – so that incendiary stories spread widely and quickly. Online tribes form echo chambers where countervailing evidence is ignored and identity signalling is rewarded. The speed and scale of contemporary communication create opportunities for polarisation that were previously unimaginable: a minor transgression can become a viral outrage, with actors mobilised from far beyond the original community.

Political polarisation in democratic societies often displays the same dynamics. Historical grievances – institutional distrust, economic dislocation, cultural shifts – become reframed in partisan terms, and partisan elites sometimes weaponise identity to consolidate power. Rhetoric that dehumanises the other side, that frames politics as a struggle to the death for the country’s soul, normalises contempt and makes compromise seem like betrayal. As with family feuds, institutional responsibilities – like independent courts, free press, and ethical norms of political conduct – either check or accelerate the spiral. When these institutions are weakened, the social costs of polarisation increase: mutual distrust intensifies, the space for deliberation narrows, and political competition transforms into mutual annihilation.

The psychological and social harms of prolonged hatred are profound and multidimensional. On the individual level, hatred corrodes mental health. It is associated with chronic stress, anxiety, and a constriction of cognitive flexibility. The energy invested in sustaining enmity could instead be used for more productive pursuits – raising children, building community, creating art. On the collective level, sustained hatred impairs cooperation, undermines economic and civic development, and increases the risk of violent conflict. It creates durable social scars that complicate reconciliation long after the immediate actors have passed away.

Yet the story of the Hatfields and McCoys also suggests that these scars are neither permanent nor uncrossable. The transition from feud to reconciliation did not happen overnight, nor was it guaranteed. It occurred amid changing economic realities, the extension of state authority, cultural shifts, and the choices of individuals who were willing to prioritize common humanity over inherited grievance. Public gestures – handshakes, joint appearances, shared celebrations – played a symbolic role, but they were meaningful because they signalled changes in underlying incentives and attitudes. Where mutual recognition replaces mutual denomination, the social psychology of hatred can be gradually reconfigured.

This remedy – replacing demonization with recognition – can be articulated more precisely in a set of practical and theoretical prescriptions. First, truth matters. Accurate historical memory, neither erased nor romanticised, helps communities understand the causes of their conflicts. In many contexts, initiatives that facilitate truthful acknowledgment of past harms – whether through historical scholarship, memorials, or public apologies – can undercut the mythology that sustains hate. The purpose is not to reopen old wounds for their own sake, but to remove the moral absolutism that justifies continuing enmity.

Second, institutional reform is essential. Where the rule of law is weak or perceived as biased, private justice and vendetta become more attractive. Strengthening impartial institutions – courts, police forces, and mediating bodies – provides alternative avenues for redress. If grievances can be addressed and remedied in ways that are seen as fair, the social logic of retaliation is weakened. Furthermore, institutions that promote intergroup contact – schools, workplaces, civic organisations – create contexts in which shared goals, repeated interaction, and equal status can diminish animus.

Third, contact and cooperation are powerful antidotes to entrenched hatred. Classic social-psychological research suggests that under the right conditions, intergroup contact reduces prejudice: when groups work toward shared objectives, when interactions are sustained, and when status inequalities are addressed, personal relationships can disconfirm negative stereotypes and humanise the other. Community-building projects that require collaboration on mutually beneficial tasks – notably economic projects, shared infrastructure, and civic improvements – can convert antagonistic relations into cooperative ones.

Fourth, education and narrative re-framing have long-term value. Curricula that teach critical thinking, media literacy, and a balanced account of historical conflicts equip future generations to interrogate inherited narratives. Civic education that emphasises democratic norms, pluralism, and the dignity of the other helps inoculate young people against simplistic black-and-white thinking. Complementarily, public narratives – those told through literature, film, and news media – that complicate villain-victim dichotomies and highlight shared humanity can reshape cultural norms.

Fifth, restorative practices offer an interpersonal pathway to healing. Unlike punitive justice, restorative processes aim to repair relationships by foregrounding the needs of victims, encouraging accountability from offenders, and facilitating mediated exchanges. Restorative justice has been applied in diverse settings – schools, communities, and transitional justice processes after mass atrocity – with variable success. Its promise lies in transforming abstract guilt into personal recognition and creating a space in which harmed persons can be heard and those responsible can make amends in concrete ways.

Sixth, economic and structural interventions matter. Material deprivation and competition amplify identity-based conflict. Policies that promote inclusive economic development, reduce inequality, and create shared prosperity reduce the structural incentives for intergroup hostility. When people’s livelihoods and prospects are secure, the allure of simplistic scapegoating diminishes.

Seventh, leadership matters. Political, cultural, and religious leaders have a disproportionate influence on public discourse. Leaders who model civility, who refuse to dehumanise opponents, and who invest in reconciliation create signals that cascade through society. Conversely, leaders who exploit grievance for short-term gain exacerbate and institutionalise hatred. Accountability mechanisms that curtail incendiary rhetoric – norms, sanctions, and institutional checks – help maintain a civic environment conducive to peaceful contestation.

None of these strategies is a panacea. Complex social problems require layered responses. History teaches that reconciliation is often messy, partial, and reversible. There are places where attempted truces have failed, where underlying injustices persisted, and where superficial gestures of peace masked unresolved resentment. Reconciliation without justice is brittle, and justice without empathy can be retributive. Effective strategies recognise the need for both accountability and restoration.

Finally, there is a moral case for resisting inherited hatred: the recognition that beneath the rituals of vengeance and the rhetoric of grievance lies a common human reality – people who love, fear, hope, and strive. To see the other as irredeemably monstrous is to deny one’s own complexity and vulnerability. Empathy does not mean condoning wrongdoing; it does mean refusing to reduce the other to a caricature and acknowledging that violence shapes victims and perpetrators alike. The Hatfields and McCoys, in their later gestures of reconciliation, affirmed this principle implicitly. When descendants met in public, when they turned sites of conflict into places of remembrance and commerce, they enacted a collective choice to reinterpret the past in a way that allowed life to move forward.

As individuals, communities, and societies confront the contemporary manifestations of the same dynamics – the polarised political arenas, the entrenched family feuds, the virulent cycles of online outrage – there is both humility and urgency in the work required. Humility, because social reconciliation cannot be imposed top-down and because the processes by which hatred takes hold are often subtle, structural, and deeply embedded; urgency, because when hatred metastasises, it degrades the public sphere, corrodes trust, and increases the risk of violence.

The alternatives are, in the end, stark. If hatred is left to its own devices, it saps energies that could be invested in innovation, community, and flourishing. It polarises societies into antagonistic camps, erodes democratic norms, and creates fertile ground for demagogues who promise simple vindication at the cost of others’ dignity. If, however, societies take seriously the lessons of history and the science of human relations – investing in fair institutions, promoting sustained intergroup contact, educating for critical citizenship, and encouraging restorative practices – the endless cycle can be interrupted.

There is a practical imperative in this reflection: each person has a role to play. In families, choosing to prioritise relationship over ancestral slights can end a chain of silence and bitterness. In communities, facilitating dialogues that bring together people with different histories and perspectives can reveal shared interests and mutual misperceptions. In the national sphere, supporting policies that build inclusive institutions and reduce structural inequalities weakens the material scaffolding of hate. In the digital realm, cultivating habits of media literacy and civility, and supporting platforms that value accuracy over outrage, can reduce the velocity at which grievances metastasise.

The story of the Hatfields and McCoys is not simply a cautionary tale about human pettiness; it is a cautionary tale about narrative formation and the social construction of identity. It shows how small causes can be absorbed into larger stories that then sustain action across generations. It also shows, crucially, that narratives can be revised and that identities can be reconstructed around new foundations: common interests, shared memories of suffering and resilience, and public rituals that emphasize reconciliation rather than reprisal.

If there is an ethical imperative distilled from these reflections, it is this: to resist the ease of inherited hatred by cultivating practices – personal, social, and institutional – that acknowledge past harms without allowing them to ossify into perpetual enmity. To remember the details of history without letting them calcify into absolutes. To build structures that offer peaceful redress for grievances, and to foster cultural norms that prize mutual recognition over perpetual condemnation.

In a world made smaller and more interconnected by technology, the stakes of how we handle grievance and difference are higher than ever. The impulses that drove the Hatfields and McCoys to violence are recognisable in new guises today: in partisan vitriol that treats opponents as enemies, in family fissures that harden into life-long estrangement, in online communities that valorise outraged identity. But the same human capacities that make hatred possible – memory, narrative, loyalty – also make reconciliation possible. We remember, we tell stories, and we teach our children. We can choose to transmit a legacy of mutual contempt or a legacy of mutual recognition.

The latter choice is harder in the immediate term because it demands empathy when one feels justified in resentment, courage when retaliation would be easier, and a long view when instant retribution promises immediate satisfaction. But it is also more generative. It permits energy to be redirected toward building lives that are not defined by struggle with an invented enemy. It opens the possibility of communities that convert their histories of violence into lessons for civic flourishing rather than into hereditary curses.

Therefore, let the tale of the Hatfields and McCoys stand not merely as a monument to the destructiveness of vendetta, but also as evidence that the chain of hatred can be unlinked. The process is incremental, often unglamorous, and requires the alignment of moral resolve, institutional capacity, and social imagination. Yet it is possible. Each handshake across a once-impassable divide, each shared memorial that acknowledges harm while refusing to weaponise it, each law that channels grievance into repair rather than retribution – all these are small victories in the long work of dismantling the propensity to hate.

In the final analysis, the fight is not against some abstract other, but against a capacity within us that misrecognises strangers as enemies and mistakes inherited anger for moral clarity. The remedy begins with recognition – recognition that the past shapes, but does not have to determine the future – and with the conscious choice to convert memory into a foundation for empathy rather than a scaffold for renewed aggression. If the descendants of two warring families can one day sit together and transform a legacy of violence into an occasion for shared remembrance and even commerce, then perhaps any community riven by enmity can do the same. The work is arduous, the gains incremental, but the moral prize – the restoration of a shared human life – is worth the effort.