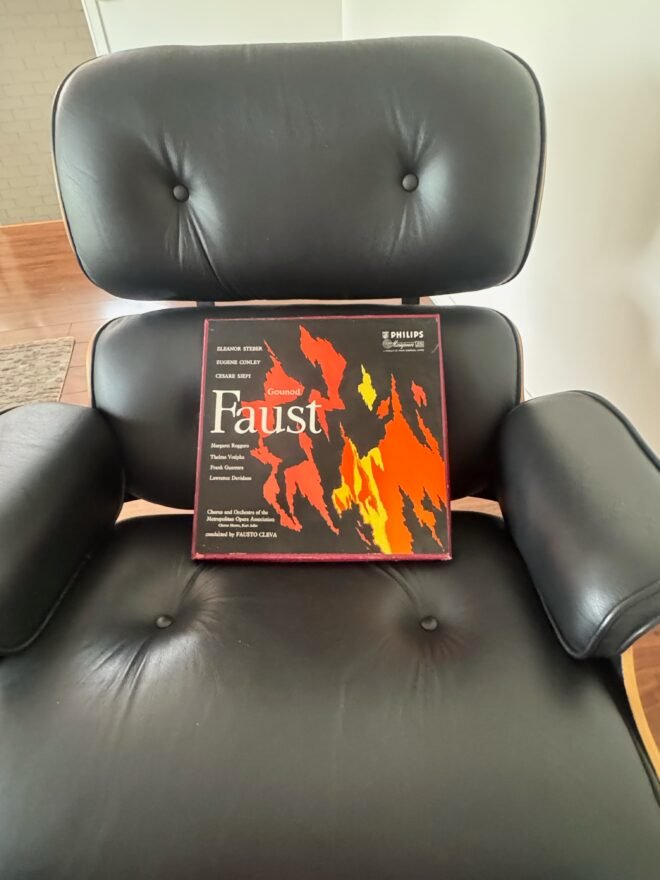

I settled into an easy chair on a quiet afternoon, the late light slanting through the curtains and a thirty-year-old single malt scotch breathing amber warmth into my glass. The needle found the groove of a Philips Minigroove 33 1/3 LP, and the room filled with the analogue patina of an earlier era – an atmosphere oddly suited to the gravity and intimacy of Charles Gounod’s Faust. The recording I put on was the 1951 Columbia studio set drawn from a Metropolitan Opera cast that had spent seasons embodying these roles onstage. There is something irreducible in that kind of performance history: singers who have lived in their parts bring an ease of response, a give-and-take, that a purely studio assembly rarely achieves. The result is not simply technical mastery; it is human presence – bright, fallible, urgent. Listening to Cesare Siepi, Eleanor Steber, Eugene Conley, and Frank Guarrera under Fausto Cleva’s direction, I heard an opera that refuses to be merely picturesque. It confronts us with moral tension, with the seductions that topple people, and with the fragile, stubborn possibility of grace.

That afternoon the music was not just aural enjoyment, but a corridor to memory. The LP I spun had been the companion of a neighbour from my childhood – a man who had survived the Holocaust. He had sat with me beside that record player in a small living room while I was still small enough to be perched on the arm of a sofa, and he had introduced me to music and literature with the urgency of someone who had seen the worst humans can do and yet remained convinced that beauty matters. He taught me Dante’s Divine Comedy and used the language of Hell to help me make sense of the inhumanity he had witnessed. He also taught me circus clown skills – how to juggle three objects, how to make an exaggerated gesture halt a conversation, how a laugh can be a shield or an indictment. Those afternoons were lessons in survival as much as instruction in art: how to use culture to outlast horror, how to find wit where cruelty wants to crush you.

The pairing of that personal memory with the 1951 Faust recording deepened my appreciation of the opera in ways that go beyond standard critical columns about casts or tempi. This is an opera born in the mid-nineteenth century but repeatedly reanimated by subsequent generations because it speaks to a human truth: the wish for more – more youth, more knowledge, more power – can be both the engine of greatness and the snare of ruin. The recording itself captures a specific post-war sensibility. Audiences and artists emerging from World War II carried a renewed hunger for meaning and redemption, a desire to rebuild and to understand how such collective moral collapse could have occurred. That context – this blend of cultural exhaustion and anxious hope – adds a resonant coloration to Siepi’s sardonic Mephistopheles or Steber’s luminous Marguerite. Here, the music is not simply ornament; it is a vessel for the era’s griefs and desires.

The 1951 Columbia recording is worth revisiting first for its artistic qualities. Cesare Siepi’s Mephistopheles is seductive and sly, a character actor who masks malice beneath a veneer of velvet. His “Le veau d’or” becomes an incisive mockery of human appetites, the aria’s sarcasm sharpened by Siepi’s dark humour. Eleanor Steber’s Marguerite moves from the freshness of youth into a collapse that is both intimate and archetypal; her voice holds light and then breaks in the right moments so that the tragic trajectory feels inevitable rather than contrived. Eugene Conley’s Faust is deliberate in its ordinariness – there is no heroic sweep, but a particular kind of moral vacuity that sits comfortably with the opera’s critique of desire untethered. Frank Guarrera’s Valentin provides the austere masculine counterweight, his baritone toughened by the soldier’s life, which makes his downfall all the more bitter. Fausto Cleva’s conducting keeps the drama taut: he knows when to let the voices breathe and when to pry the tension forward. He also follows a mid-century performance practice in excising the Walpurgis Night ballet, preferring to keep the focus on the human moral drama rather than elaborate spectacle.

That editorial choice is telling. The Walpurgis episode is often included for its colour and carnival grotesquery, but the Cleva set pares the work back to its moral essentials. The omission sharpens a narrative that centres on Faust’s internal transaction and its collateral damage – especially to Marguerite. In the early 1950s this focus made sense: Europe was less interested in fantastical diversions and more in confronting the ethical aftermath of a war that had dehumanised millions. Opera houses were sites of cultural recovery; performances of works like Faust offered not mere entertainment but communal reflection. The Metropolitan Opera, under Rudolf Bing, was assembling international casts that might in their diversity suggest a post-war cosmopolitanism – an implicit answer to the xenophobia and wilful ignorance that had led to catastrophe.

Yet to appreciate what Gounod’s Faust does – what it tries to ask and answer – we must look back to the source. The opera draws not from the medieval legend alone, but most crucially from Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s monumental two-part drama. Goethe’s Faust is a vast philosophical odyssey. Part I is intimate and tragic: an aging scholar, disillusioned with the limits of human knowledge and the banality of everyday life, encounters the embodiment of negation – Mephistopheles – who offers him a bargain. Faust will receive renewed youth and the pleasures of life if, upon a moment of absolute satisfaction, his soul may belong to the Devil. Faust’s romance with Gretchen (or Marguerite) ends in the ruin of the innocent woman and the redemption of her soul through the grace denied to Faust in that text. Part II expands into allegory and cosmology, with Faust engaged in projects of human improvement that are ultimately vindicated, and his salvation is secured by the ethic of striving – the idea that the human who continually labours to better himself and others partakes in a kind of redemption.

Gounod’s operatic adaptation – his libretto by Jules Barbier and Michel Carré – condenses and simplifies. Of necessity, opera privileges immediacy: arias, ensembles, and the visual theatre demand a compression of philosophical inquiry. Gounod selects the intimate moral tragedy of Part I and heightens its emotional stakes. Marguerite becomes the central figure in a way that accentuates the gendered consequences of Faust’s selfishness. The opera dwells in the interpersonal: Faust’s loneliness, Marguerite’s innocence turned to despair, Mephistopheles’ sardonic manipulations. This is a work of nineteenth-century French sensibility, attentive to melody, sentiment, and the moral clarity typical of the period. Where Goethe’s poem shades character motivations into ambiguity and speculation, the opera offers a clearer moral compass: the innocent are saved; Faust’s eternal fate is sealed by his bargain. The shift is not merely stylistic. It signifies a culture that sought the consolations of faith and narrative closure in an age where romanticism was still a powerful cultural force.

That contrast – Goethe’s ambiguous metaphysical epic and Gounod’s concentrated moral melodrama – matters because it illuminates how societies rework myths to answer their pressing questions. In nineteenth-century Europe, the Faust story functioned as a frame for anxieties about modernity: the new sciences, the myth of human mastery over nature, and the erosion of traditional belief systems. By the mid-twentieth century, after two world wars and the apocalypse of genocide, the same tale was read through a different lens: not merely a meditation on knowledge but a ledger of ethical responsibility and complicity. My neighbour’s readings – he linked Faust with Dante – were not idiosyncratic. Dante’s Inferno had always provided a map of culpability, a taxonomy of sin. The bonds between treachery, ambition, and consequence in Dante’s frozen ninth circle rang cruelly familiar to someone who had watched people betray basic humanity in the camps. The metaphor of an individual bargaining for earthly satisfactions at the cost of the soul took on literal overtones in the face of wartime collaboration and atrocity.

This is where the opera’s personal and the historical intersect. Mephistopheles, as rendered by Siepi, is not only a metaphysical tempter; he is a satirist who exposes how folly masquerades as desire. This makes the devil a figure of dark truth-telling: he articulates what people refuse to admit about their appetites. The clownishness – the gift of jocular cruelty – echoes the circus lessons from my neighbour. Clowns historically often occupied a paradoxical place: they could point out truths those in power overlooked precisely because humour dislodged decorum. My neighbour’s juggling and mugging taught me not only a few tricks but also a stance: to face horror with both wit and witness. There is a world in which laughter is a survival technique, and where the ability to mask pain with movement becomes an ethics of endurance. That the opera contains comic contamination in Mephistopheles is not incongruous; on the contrary, it makes the work truer to life. Human tragedy rarely arrives without irony.

A central ethical question in Faust is whether ambition is inherently corrupting. Goethe’s answer leans toward redemption through striving: the restless, imperfect human who keeps moving forward may be saved by the righteous exertion itself. Gounod’s moralisation is stricter: Faust’s hunger leads to direct, human cost. Marguerite’s fall is not simply collateral damage; it is the moral reckoning for Faust’s egoism. This dualism – striving as noble, desire as dangerous – has contemporary echoes. Consider scientific and technological advances: the same curiosity that unlocks life-saving treatments can birth weapons of mass destruction. Classic twentieth-century figures – Oppenheimer, for instance – embody this ambivalence. Their genius pursued the limits of knowledge but thereby unleashed possibilities of unprecedented harm. Faust’s pact is less about intellectual wanting than about the ethical structure around wanting. What constraints and responsibilities govern human search for more? In an era of climate crisis, unchecked resource extraction, and AI development without robust oversight, the Faust myth has newly urgent resonance.

Temptation does not come to Faust in abstract slogans; it comes as the immediate promise of remedy to loneliness, as the conjuring of a return to youth that dissolves the scholar’s isolation. In the opera, Mephistopheles trades in the appearance of ease. He simplifies the human dilemma into a commercial transaction: pleasure now for eternity lost. The bargain’s appeal is not metaphysical complexity but psychological immediacy. In a consumer age, this sells. Today’s social media culture, with its trade-offs of privacy for attention, feels Faustian. We exchange interiority for external validation, and we do so in transactions that feel involuntary because their harms unfold slowly. The opera directs our attention to how desire erodes ethics, how seduction minorities into moral blindness.

Marguerite’s suffering raises another set of questions, specifically gendered ones. Her downfall, at the hands of Faust’s selfishness and Mephistopheles’ manipulation, gestures toward the real-world pattern of women paying the cost for male transgression. Gustave Flaubert and other nineteenth-century writers mapped that dynamic in literature of the period, and the opera inherits it. Marguerite is romanticised and punished; she is both central and erased. From a contemporary vantage, her story invites questions about agency and culpability. How do social structures facilitate the exploitation of innocence? How does the judgement of women in moral terms reflect broader patriarchal controls? These concerns resonate with present-day movements toward accountability. Marguerite’s redemption – through faith and confession in the opera – feels double-edged: it restores dignity but only by reinserting a moral order that may not attend to the systemic injustices that shaped her vulnerability.

Redemption, finally, is the needle the text tries to thread. Goethe and Gounod offer different seams. Goethe’s divine chorus suggests a cosmic charity toward the striving human. Gounod’s conclusion rehearses the consolations of Christianity. Both insist that the capacity for transformation matters. But neither evades the terrors of human culpability. Even the prospect of salvation does not erase the suffering caused by human appetites. That complexity matters because it resists simplistic moralising. The opera does not demand one reconcile desire and ethics neatly; it insists that we hold both truths at once: that striving can redeem and that the injuries of unchecked desire are real and reparative only with deep accountability.

Listening to the 1951 recording with the sediment of personal memory layered on top changed how I receive these universal ideas. My neighbour’s life offered a hard counterpoint to melodramatic abstractions. He had lived through bullies and systems that willingly dehumanised neighbours; for him, “devils” were faces and policies. Yet he turned to opera and Dante and to clownish gestures as a means of reconstructing life. He treated culture not as an escape but as a resource for repair. That, to me, reframes Faust. The opera becomes not merely an argument about metaphysics but a model for how art can help people live through devastation and find a vocabulary for moral judgment. The knowledge of atrocities does not remove our capacity for wonder, but it situates wonder with caution and responsibility.

There is also a small, sensory pleasure in the record’s analogue warmth: the micro-scratches, the slight hiss, the way dynamics breathe into the room. Vinyl listening is a deliberate act. It demands time and attention. You put on a side and commit yourself. There is a ritual that aligns well with Faust’s themes: the bargain behind the listening experience itself is simple but telling – time sacrificed for concentration, distractions deferred for engagement. In the age of streaming, where music is often decentralised into fleeting bites, the vinyl ritual recalls an ethic of care. The performance on that 1951 disc rewards such care. It repays listening with the detail of phrase and the drama of human interplay.

Comparatively, Faust has had many other adaptations, each refracting the legend through different cultural air. Berlioz’s La Damnation de Faust is musically audacious and far less drinkable to casual audiences; Boito’s Mefistofele tilts the story into grand irony and a cosmic scale. Modern stagings – some casting Faust in the light of modern capitalism or technological hubris – underscore that the story’s elasticity is its greatest power. The opera’s popularity has waxed and waned precisely because each generation asks, in its own terms, who sells out and who is redeemed. When I listen to the 1951 set, I hear post-war Europe trying to reconcile its collective guilt and grief; when I watch a 2011 production that transposes Faust to an atomic age, I see a twenty-first-century anxiety about annihilation and hubris.

The broader implications, then, are straightforward but urgent. Faust holds us accountable to the consequences of desire. It invites reflection on how personal choices cascade into communal harm. It also warns against facile optimism: salvation, if possible, often comes at a price that requires restitution and humility rather than mere intention. On the other hand, it offers a counterargument to despair – that even when the world seems to have failed, humanity’s capacity to love and to labour toward the good can become the grounds for redemption.

As a blogger reflecting on these threads, I want to summon what the art insists: that the human story is irreducibly paradoxical. We are creatures of aspiration and of appetite; we can do the grandest things and the vilest. Art helps us see that complexity with compassion and clarity. The 1951 Faust is a living instance of this: a document of performers steeped in their roles, an artifact of a post-war cultural project, and an occasion for private remembrance. My neighbour, who survived the camps and introduced me to Dante and clowning alike, taught me that art can be a lantern in a long tunnel, not because it softens horror but because it helps translate it into meaning. He taught me also to laugh in the face of evil, not to mock suffering but to reclaim some autonomy in its shadow.

The final image of that listening afternoon remains vivid: the scarlet swirl of the single malt in my glass, the stylus tracking the recorded voices, the music making old wounds into something like curriculum. Faust – Gounod’s particular take on the medieval and Goethean legend – remains necessary because it houses these contradictions: temptation and accountability, comedy and cruelty, despair and redemption. If the opera compels us to look inward and outward with equal scrutiny, if it urges us not to sell our souls for immediate gratifications, then its relevance persists. Maybe I should have pursued the clown’s path my neighbour suggested – embracing the paradoxical role of the wise fool. But even as I write and think and sip, I recognise that the life of the mind, like the clown’s performance, can be an ethical stance. To attend to art with honesty is to refuse easy bargains and to insist on a world in which beauty bears the memory of the wrong it must help rectify.

In the end, the recording is both artefact and adviser: a post-war gem that demonstrates how performance practice, historical circumstance, and individual memory meld to produce a reading that is at once historical and hauntingly current. Gounod’s score, Goethe’s philosophic skeleton, Dante’s punitive geography, and my neighbour’s lived testimony come together to teach a lesson about the human condition. We strive, we fall, and sometimes grace finds us in unexpected quarters. That lesson is why I keep the LP on my shelf and why I return to Faust’s music when the world grows unkind. It is also why, in a global moment steeped in technological temptation and environmental peril, the tale of Faust still asks the essential question: at what cost do we reach for more, and what are we prepared to give in return? The answer is never easy, but the opera’s enduring power is that it forces us to wrestle honestly with the trade-offs and, perhaps, to choose differently.