Social media is a modern agora where ideas collide at lightning speed, where conviction often outpaces knowledge and where the contours of history can be flattened to fit a headline or a meme. Recently I found myself drawn into such a contest on X (formerly Twitter): an anonymous antagonist – who claimed affiliation with a populist political party and corporate pedigree – offered a pithy but demonstrably flawed interpretation of a foundational moment in Australian legal history. He insisted that the 1836 decision in R v Murrell was a turning point that effectively granted Indigenous Australians equal protection under the British Crown from the earliest days of colonisation. That reading, conveyed with the confident simplicity of internet certainty, was not merely mistaken; it masked the complex and systematic processes by which colonial law was deployed to dispossess, control and marginalise Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples.

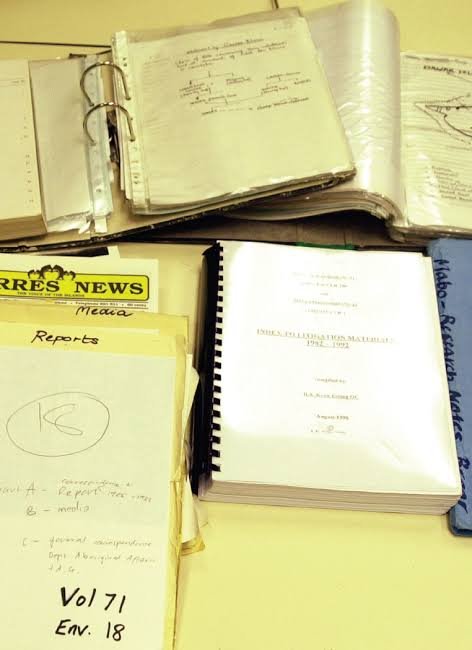

That encounter was more than a one-off irritation. It exemplified a persistent problem: a superficial grasp of legal and historical realities in which selective facts are lifted and recontextualised to support contemporary political narratives. My own work – three articles on this subject on my blog BlakandBlack, including a long-form piece titled “Superfluous People” (April 1, 2011) – has sought to probe beneath the surface, to examine primary sources and scholarly analyses that reveal a very different picture. Far from inaugurating equality, the Murrell decision helped cement a legal regime that denied collective rights, ignored customary law, and sanctioned a pattern of “anticipation without consummation” – promises or illusions of protection and inclusion that were repeatedly betrayed.

This extended post will set out that history: the richness of pre-colonial Indigenous societies, the mechanics and consequences of invasion, the prolonged and bloody Frontier Wars, the legal manoeuvres exemplified by R v Murrell, the demographic and social catastrophe that followed, the institutionalisation of racist policy at Federation, the trauma of the Stolen Generations, the limited hope of the 1967 referendum, and the ongoing struggles and aspirations of Indigenous peoples today. Throughout, I draw on a variety of sources – archaeological and anthropological evidence, court records and parliamentary debates, missionary journals, Indigenous testimony, and contemporary historical scholarship from voices such as Henry Reynolds, Lyndall Ryan, Bruce Pascoe and others – to present a coherent narrative that dismantles myths and honours resilience. The aim is not polemic for its own sake but clarity: a sober, historically grounded account that can inform the public conversation about justice, recognition and reconciliation.

Pre-Colonial Australia: A Thriving Mosaic of Nations and Cultures

Any honest account must begin with what colonisers denied: the existence of fully formed, sophisticated societies across the Australian continent. For tens of thousands of years – conservative archaeological estimates now place human presence in Australia at least 65,000 years – Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples developed cultures, political systems, spiritual frameworks and environmental practices of extraordinary complexity and adaptability.

The notion of terra nullius – the idea that the land was empty and available for settlement – was not an empirical observation; it was a legal fiction designed to justify dispossession. In reality, the continent supported diverse lifeways: coastal peoples maintained shellfish economies and complex maritime knowledges; inland groups managed water resources and seasonal cycles; the Gunditjmara in what is now Victoria constructed multi-layered aquaculture systems at Budj Bim; Yolngu communities in Arnhem Land maintained extensive ceremonial and trade connections; and hundreds of distinct nations with their own languages, laws and social structures inhabited defined territories.

Social organisation combined communal responsibilities with sophisticated forms of governance. Kinship systems governed land tenure, marriage, dispute resolution and ceremonial obligations. Elders and law-keepers wielded moral and ritual authority, while customary law – transmitted through oral histories, songlines and ceremony – regulated everything from resource use to retributive practices. Far from being “primitive” in a simplistic sense, many societies practised forms of land management that Europeans would later misrecognise as agriculture. Bruce Pascoe’s work in Dark Emu, for example, highlights archaeological and ethnohistorical evidence of plant cultivation, food storage and settled village life in various regions – practices that undermine the myth of an unpeopled, unclaimed landscape.

Environmental stewardship was integral to social order. Indigenous fire regimes – often called “fire-stick farming” – were used to promote biodiversity, regenerate pastures and manage fuel loads. These practices demonstrate a knowledge of ecology that governed human-land relationships. Spiritual cosmologies, often expressed as Dreaming or Dreamtime narratives, interlinked law, land and identity: country was not a commodity but a living entity imbued with ancestral presence and moral meaning.

Understanding this pre-colonial sophistication is essential because it reframes dispossession not simply as a loss of territory but as the dismantling of entire orders of being. When colonial institutions dismissed Indigenous law and governance as irrelevant or non-existent, they were not merely asserting sovereignty over space; they were asserting sovereignty over meaning, identity and law itself.

The Arrival of the Invaders: 1788 and the Dawn of Systematic Betrayal

The arrival of the First Fleet in 1788 marks a rupture whose consequences resonate to this day. The establishment of the colony at Sydney Cove under Governor Arthur Phillip was not accompanied by treaties or formal agreements with the peoples whose lives and lands were transformed. The Crown’s claim to sovereignty – asserted unilaterally and defended legally by doctrines like terra nullius – laid the groundwork for dispossession.

Initial encounters were complex and uneven. There were moments of exchange and curiosity, and figures such as Bennelong and Barangaroo became strikingly visible in early colonial accounts. Yet beneath these interactions lay structural asymmetries. Disease proved catastrophic: smallpox and other introduced illnesses swept through Indigenous populations with devastating efficiency, often preceding or accompanying the physical encroachments of settlement. Contemporary observers recorded scenes of mass death along riverbanks and in camps, scenes that are difficult to reconcile with narratives of peaceful settlement.

Colonial administrations oscillated between rhetoric of protection and actions of dispossession. Governors often issued proclamations invoking the Crown’s supposed benevolence and legal safeguards; in practice, the demands of colonial expansion – land for grazing, labour for agriculture and infrastructure, and the perceived needs of a growing settler society – drove policies that dispossessed Indigenous communities and criminalised resistance. Military expeditions were authorised against groups labelled as “hostile,” and punitive reprisals were sometimes meted out with scant attention to due process.

Missionaries arrived with an intertwined mission of spiritual conversion and social regulation. Their records reveal a mixture of sympathy, paternalism and cultural imperialism. Institutions established for children – early antecedents of later assimilationist schools and missions – sought to eradicate language, custom and identity in the name of civilisation. These efforts constituted more than cultural interchange; they were attempts to subordinate Indigenous social structures to colonial norms.

The early decades of colonisation thus set patterns that would become entrenched: dispossession backed by force and law, pandemics that decimated communities, and a civilisational discourse that justified assimilation as benevolence. For Indigenous peoples, the “anticipation” of reciprocal engagement and mutual recognition gave way to the repeated betrayal of promises from the very inception of colonisation.

The Frontier Wars: A Bloody Saga of Resistance, Massacres, and Erasure

The expansion of pastoral settlement into the interior triggered a prolonged and bitter conflict – the Frontier Wars – that has too often been marginalised in national histories. Far from isolated skirmishes, these encounters comprised a sustained conflict in which Indigenous groups resisted dispossession with skill and determination, and settlers, backed by colonial forces and often by officially sanctioned paramilitary units, responded with violence, intimidation and systematic practices of extermination and displacement.

The scale of this violence is vast. Across the continent, incidents ranged from targeted reprisals and massacres to systematic “dispersals” carried out by Native Police units under colonial command. Tasmanian history records a particular case of near-eradication – what is often called the Black War – where policies and practices led to catastrophic population loss and cultural dislocation. In other regions, such as Queensland, the establishment of Native Police forces facilitated what many historians describe as punitive expeditions that led to mass killings and the territorial consolidation of settler control.

Tactics used against Indigenous communities were brutal and varied: drive hunts that forced people over cliffs, baited wells and waterholes, poisonings, and coordinated attacks designed to terrorise communities into abandoning land. The language used to justify these measures – descriptions of groups as “hostile” or “subhuman” – dehumanised victims and normalised extraordinary violence. Settler vigilante actions and state-sanctioned force blurred together in ways that made accountability difficult and historiography contested for decades.

Indigenous resistance took many forms: guerrilla-style raids on stock, the leadership of charismatic fighters and strategists like Pemulwuy, Yagan and others, and diplomatic efforts to preserve access to country and resources. The enduring fact is that Indigenous peoples resisted creatively and persistently, and that their struggles were met with forms of state-sanctioned violence that have shaped demographic, cultural and political trajectories ever since. The Frontier Wars left a legacy of trauma, dispossession and historical erasure that remains central to contemporary debates about recognition and redress.

R v Murrell: Legal Erudition as a Veil for Oppression

Amid this broader context of conflict and dispossession, the 1836 decision in R v Murrell stands as a pivotal moment in the legal ordering of colonial society. The case concerned an Indigenous man accused of killing another in the course of a tribal dispute. The question posed to the colonial court was not merely technical; it probed the very reach of British law across a continent whose Indigenous systems of law and governance had been systemically disregarded.

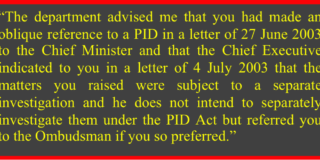

In his judgment, Justice William Burton articulated a view of colonial authority that rejected any legal autonomy for Indigenous societies. By asserting that Australia had been settled rather than conquered, Burton effectively framed the Indigenous inhabitants as subjects under the Crown who did not possess a parallel legal sovereignty that might exempt them from colonial courts. In doing so, the judgment claimed to offer protection under common law; yet the protection was of an individualised and subordinated kind. Customary laws, collective rights to land, and the institutional integrity of Indigenous governance were not recognised as sources of legal standing.

This legal positioning had profound implications. By treating Indigenous law as inessential to the colonial legal order, R v Murrell neutralised a crucial avenue of Indigenous self-determination. It legitimised the notion that Indigenous communities could be governed, disciplined and reconfigured through the mechanisms of colonial law, while denying them the right to regulate relations internally according to their customs. Whereas some early encounters in other colonial contexts involved treaties or negotiated arrangements that acknowledged at least some form of Indigenous polity, R v Murrell helped consolidate a jurisprudential framework that dismissed such possibilities in Australia.

Over subsequent decades, the logic of Murrell reverberated through legal doctrine and administrative practice. It underpinned decisions and policies that treated Indigenous peoples as objects of paternalist regulation rather than as rights-bearing collectives. The doctrine of terra nullius – matured in subsequent judicial formulations like Cooper v Stuart and ultimately confronted in Mabo v Queensland (No 2) in 1992 – found reinforcement in judgments like Murrell, which prioritised the Crown’s legal instruments over Indigenous systems of law and land tenure. The result was a legal architecture that both masked and facilitated dispossession.

The Catastrophic Human Cost: Demographic Collapse and Stealth Genocide

The human consequences of colonisation were calamitous. Demographic collapse across the continent was driven by a lethal combination of introduced disease, frontier violence, displacement from resources and breakdowns in social and ecological systems. Pre-contact population estimates vary – conservative figures often cited range from several hundred thousand to over a million people – but by the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries Indigenous population numbers had plunged dramatically. In some regions the losses were existential.

Disease – including smallpox, influenza, tuberculosis and sexually transmitted infections – played a central role. The vulnerability of Indigenous populations to these diseases, coupled with the rapid spread facilitated by colonial mobility and settlement networks, produced mortality that devastated communities and undermined their capacity for social reproduction and resistance.

Violence and policies of containment further deepened the crisis. The coercive appropriation of land disrupted food and resource systems, leading to malnutrition, exposure and dependence on settler rations. In many contexts, reproductive autonomy was violated and family structures were intentionally undermined by authorities who deemed assimilation a reasonable aim. Practices such as forced child removal – central to later Stolen Generations policies – functioned as mechanisms of cultural destruction.

Scholars such as Colin Tatz have argued that the cumulative effect of these policies and practices amounts to “genocide by stealth” – a suite of actions that, while not necessarily always framed by contemporaries in genocidal language, fell within the predictive contours of modern definitions of genocide in their impact on the physical and cultural survival of groups. The United Nations Genocide Convention’s categories – killing members of a group, causing conditions of life calculated to bring about physical destruction, deliberately inflicting measures to prevent births, forcibly transferring children – map uncomfortably well onto aspects of Australia’s colonial and early federal history.

This demographic catastrophe was not simply an unintended side effect of colonisation; it was foreseeable and was facilitated by legal and administrative systems that privileged settler interests and treated Indigenous lives as expendable. The long-term consequences – gaps in population, loss of knowledge-holders, ruptured cultural transmission – have continued to reverberate across generations.

Federation and the Institutionalisation of Racism: From “Problem” to Assimilation Policy

The formal union of the Australian colonies in 1901 further institutionalised exclusionary frameworks. The new Constitution contained provisions that explicitly marginalised Indigenous peoples. Section 51(xxvi) gave the Commonwealth power to legislate “for the people of any race,” while section 127 excluded Indigenous Australians from population counts for constitutional apportionment. These clauses did more than reflect demographic calculations; they signalled a constitutional invisibility that both reflected and reinforced public and political attitudes of the period.

Across the states, protectionist regimes proliferated in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Legislation such as the Protection Acts and the Aboriginals Protection and Restriction of the Sale of Opium Act in Queensland created an architecture of control: reserves and missions, stringent permit systems for movement, guardianship regimes that stripped adults of legal authority over their children and exploitation of Indigenous labour through withholding of wages. Such systems were explicitly premised on a racialised hierarchy – the view that Indigenous peoples were either a “dying race” or a people to be absorbed into white society.

By the interwar and postwar decades, policy shifted toward assimilation. Official discourse framed assimilation as a benevolent project: an attempt to bring Indigenous peoples into the economic and cultural life of the nation. In practice, assimilation entailed further erasure of distinct identities. Children were removed from families and placed in institutions or white foster homes; language and ceremonial practice were discouraged or punished; and employment and health policies often subordinated Indigenous wellbeing to the imperatives of labour markets and settler governance.

Institutional mechanisms – boards and protectors – exercised sweeping powers with minimal accountability. In many cases, the law enabled the dispossession of land and the extraction of labour under the guise of protection. The legacy of these policies is visible in socioeconomic disparities, intergenerational trauma and the loss of cultural continuity.

The Stolen Generations: A Heartbreaking Chapter of Cultural Erasure

The practice of forcibly removing children from their families stands as one of the most wrenching and enduring legacies of assimilationist policy. The Stolen Generations – broadly dated from the late nineteenth century through the mid-twentieth century, with removals continuing into the 1970s – encompass thousands of children taken for reasons that ranged from ostensibly protective motives to deliberate social engineering.

Authorities – including Chief Protectors, missionaries and welfare institutions – rationalised removals with language of “rescue” or “civilising,” particularly when targeting children of mixed descent. Internal records and survivor testimonies disclosed in inquiries and in the Bringing Them Home report (1997) reveal practices that severed children’s language, connection to kin and cultural practices. Many survivors endured neglect and abuse in institutions and foster placements. The psychological and social consequences have been profound: higher rates of suicide and mental illness among generations affected, disrupted parenting capacity, and widespread feelings of loss and dislocation.

The Bringing Them Home report was a watershed in acknowledging the scale and trauma of these removals. It documented the stories of survivors, the policies that enabled removal, and the need for reparative responses including apologies, compensation and support for healing. The 2008 National Apology moved symbolic justice forward, yet structural remedies – compensation schemes, national reparations, and comprehensive healing programs – remain uneven across jurisdictions. The enduring harm of the Stolen Generations continues to shape contemporary debates about justice and recognition.

The 1967 Referendum: A Watershed Moment of Hope and Limitation

The 1967 referendum was a pivotal moment in the long arc of Indigenous political mobilisation. Campaigners, organisations such as the Federal Council for the Advancement of Aborigines and Torres Strait Islanders (FCAATSI), and leaders like Faith Bandler successfully mobilised public sentiment to amend the Constitution. The changes removed discriminatory language that had excluded Indigenous people from the census and allowed the Commonwealth to make special laws for Indigenous Australians.

The referendum’s overwhelmingly positive vote – over 90% in favour – was an affirmation of popular support for change, yet its legal and practical effects deserve careful qualification. The referendum did not immediately transform socioeconomic conditions, nor did it automatically confer political or cultural sovereignty. It did, however, open avenues for federal involvement in Indigenous welfare, health, housing and later land rights processes. The post-referendum decades saw a complex mixture of progress – such as the eventual recognition of native title in Mabo – and persistent structural disadvantage. The referendum was a turning point in public recognition, but not an endpoint.

Contemporary Reflections: Persistent Disparities and the Path to Sovereignty

Indigenous Australia today is characterised by resilience, cultural revival and political assertion, alongside persistent disadvantage and ongoing contestation over land, recognition and justice. Demographically, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples now number over 800,000, forming a vibrant and growing portion of the national population. Yet stark disparities remain in life expectancy, health outcomes, incarceration rates, educational attainment and economic participation.

Systemic issues – overrepresentation in the criminal justice system, deaths in custody, inadequate housing and threats to sacred sites – continue to generate national concern and activism. The 2023 referendum on a constitutional Voice to Parliament, and its rejection at the ballot box, revealed enduring divisions in the public imagination: desires for symbolic and constitutional recognition meet apprehensions about change, sovereignty and political power.

Alongside these challenges, Indigenous communities continue to secure important victories. Native title claims, cultural renaissance movements, language revival projects and successful land management initiatives reflect a determination to sustain and renew cultural life on ancestral country. The Uluru Statement from the Heart – calling for a Makarrata Commission, truth-telling, and a constitutionally enshrined Voice – offers a roadmap for deep structural recognition and partnership, centred on Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination.

What is demanded now is not simply symbolic apology or periodic policy intervention but structural transformation: truth-telling about history, meaningful measures to close socioeconomic gaps, legal recognition of Indigenous custodianship and rights, reparations where appropriate, and institutional arrangements that enable Indigenous peoples to exercise authority over health, education, land management and cultural heritage. This transformation requires sustained political will, honest public deliberation and concrete policy frameworks grounded in partnerships with Indigenous communities.

Conclusion: Dismantling Myths, Honouring Resilience, and Demanding Justice

The flattened interpretation of R v Murrell that I encountered online – claiming it a magnanimous act of equality – illustrates how partial readings of legal history can be marshalled to sanitise and justify ongoing injustice. A fuller historical reckoning reveals a different truth: Murrell was not a watershed of protection but part of a legal logic that subordinated Indigenous law and legitimised dispossession. It sits within a broader pattern: initial encounters fraught with disease and deceit, protracted and bloody frontier conflict, juridical instruments that refused to acknowledge Indigenous sovereignty, and policies that sought cultural erasure through assimilation and child removal.

Yet this narrative is not merely one of victimhood. Across centuries of oppression, Indigenous peoples have resisted, adapted and preserved cultural strengths that inform contemporary claims to rights and sovereignty. From land management practices that predate colonial arrival to contemporary court victories and political mobilisation, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples continue to assert their place in Australia’s past, present and future.

For non-Indigenous Australians, the task is simple in principle though demanding in practice: listen to Indigenous voices, support robust truth-telling, endorse legal and constitutional measures that recognise Indigenous sovereignty and authority, and pursue reparative policies that address the material and cultural consequences of colonisation. For historians, lawyers and citizens alike, the obligation is to reject facile readings and to pursue a historical understanding that is honest, nuanced and consequential.

If reconciliation is to mean anything substantial, it must rest on the twin pillars of truth and justice. Only when we acknowledge the realities of the past – its violence, legal subterfuge and moral failures – can we begin to fashion institutions and relationships worthy of the term “consummation” rather than perpetual anticipation. The history I have outlined is uncomfortable, at times harrowing. It is also a source of possibility: a sober foundation on which genuine partnership, redress and recognition can be built. That is the work that history demands of us, and it is the obligation that justice requires.