This is the second of my Australia Day 2026 Indigenous spirituality posts.

Introduction

Baiame (also recorded as Biame, Baayami, Baayama, Byamee) occupies a central place in the cosmologies of many peoples of southeastern Australia. Revered as a creator spirit and sky father among communities such as the Gamilaraay (Kamilaroi), Wiradjuri, Euahlayi and neighbouring language groups, Baiame occupies the liminal space between ancestor, lawgiver, and celestial guardian. Stories of Baiame are passed through song, ceremony, rock art and oral tradition; they form part of the living body of knowledge commonly referred to in English as the Dreaming or Dreamtime – an expansive worldview in which ancestral beings enact and sustain the patterns of land, law and human life.

This essay seeks to present a considered, respectful and detailed account of Baiame: his historical and cultural context; the major mythological narratives associated with him; symbolic representation and artistic depiction; the social and legal frameworks his teachings support; comparisons with other creator spirits in Australian Indigenous traditions; and his continuing relevance in contemporary cultural revival, law and environmental practice. Where appropriate, the text will indicate that accounts differ among groups and that much sacred knowledge remains culturally sensitive; readers should approach these traditions with humility and respect for Indigenous custodianship.

Historical and Cultural Context

Understanding Baiame requires situating him in the deep time of Aboriginal Australia and in the particular landscapes of southeastern New South Wales. Human presence in the region extends for many tens of thousands of years, and over that span oral histories, songlines and material culture have fused to generate regionally specific yet interconnected traditions. The Gamilaraay and Wiradjuri peoples, for example, maintain complex systems of kinship, totemic affiliation and land stewardship that are both social practice and cosmological enactment. In these systems, creator-beings such as Baiame are not remote metaphysical abstractions: their actions are read in the landforms, hidden waterholes, rock shelters, and stars, and their laws are performed and renewed through ceremony.

Colonial contact from the late eighteenth century profoundly altered the circumstances in which these traditions survived. Missionary accounts, early ethnographies and police and settler records – of which the writings of A. W. Howitt and R. H. Mathews are notable examples – recorded Baiame as a principal figure. These recordings were filtered through European frames of reference; some early observers drew comparisons between Baiame and the Judeo-Christian God, or presented him within a monotheistic interpretation that did not fully capture the relational, ceremonial and place-bound dimensions of Aboriginal spirituality. Despite dispossession, displacement to missions and government policies designed to assimilate Indigenous people, Baiame’s narratives and associated practices persisted, often maintained under difficult conditions by elders and ceremonial custodians.

Baiame is bound to particular sacred places – rock-shelter paintings and carved motifs bearing his likeness still exist in sites such as the so-called Baiame Cave in the Hunter Valley region. These sites function as much more than historical artifacts: they are living markers of custodial responsibility and memory. The traditions surrounding Baiame also intersect with gendered ritual practice. While he is commonly referred to in masculine terms as a “sky father,” the cosmology is relational: female creator figures such as Yhi (a sun woman in some narratives) or local female ancestral beings complement Baiame’s actions, emphasising the reciprocity and balance that underpin social and ecological relations.

Mythological Narratives

Across communities, narratives about Baiame vary in emphasis and detail, but certain recurring motifs are evident: creation of landscapes and beings, the giving of law, the establishment of kinship and ceremonial frameworks, and ongoing oversight from the sky. The following selection of stories and narrative strands is drawn from community knowledge as recorded and recounted in ethnographic sources and contemporary oral histories; these versions are offered with the recognition that specific and sacred ceremonial knowledge is rightly custodial and not for public dissemination in full.

Creation and Shaping of Country

Many accounts portray Baiame as a sky-being who descends to a world that is formless or imbalanced and then shapes the land. He carves rivers, forms mountains and arranges the lay of the country. In some traditions he forms humans from red clay or from carved figures, then breathes life into them. This framing – creation that is both sculptural and nurturing – positions human beings as animate components of a living landscape rather than as dominators of it. The places Baiame creates have moral as well as physical significance: waterholes left by his footsteps become sacred sites, and particular ranges or gullies bear the imprint of an ancestral event, a story that instructs local people in how to behave towards one another and towards the environment.

Baiame, Yhi and the Light of Creation

The interplay between Baiame and female creator figures is central in many stories. In some retellings, Yhi – the sun woman – brings light and warmth to the newly formed world, stimulating growth and activity. Baiame’s role as sky father and Yhi’s role as solar bringer together articulate a cosmology in which creation requires complementary forces: the vast, overseeing presence and the life-giving intensity of light. These motifs are not merely poetic: they map onto seasonal cycles, food availability and ceremonial time, and they serve as mnemonic frameworks for transmitting ecological knowledge.

Law-Giving and the Establishment of Social Order

Baiame’s authority is most immediately expressed through law. Many stories describe him teaching people how to live: he prescribes marriage rules, kinship systems, mourning practices and taboos governing hunting and resource use. The bora initiation – male initiation ceremonies practiced across much of southeastern Australia – is commonly linked to Baiame. In bora ceremonies, sacred grounds are prepared and sequences of ritual re-create aspects of the ancestral events by which the world was ordered. Through these rites, young people are inducted into knowledge, responsibility and the moral economy of the group. The laws Baiame hands down are relational: they regulate how people relate to place, to kin and to the non-human world.

Discipline and Punishment

Within the corpus of Baiame narratives are accounts of punitive action, often expressed as natural phenomena (floods, droughts, storms) which follow human transgression. Such tales function pedagogically: they reiterate the consequences of violating the laws or the pacts underpinning custodial responsibilities. These narratives also place ultimate authority beyond the ephemeral human realm and thus support communal mechanisms for restorative action, reconciliation and the re-establishment of balance.

Celestial Embodiment and Ongoing Presence

Although Baiame is credited with shaping the earthly domain, many traditions describe him afterwards ascending to the sky to dwell among the stars. The Milky Way is sometimes conceptualised as Baiame’s pathway or camp, and particular constellations may be narrated as his tools, footprints or family. In such a cosmology, the sky is not distant abstraction but an active, watching presence that remains available to people in dreams and visions. Elders and ritual specialists may receive guidance from Baiame in the form of dream visitations. This ongoing presence underlines a crucial feature of Dreaming thought: ancestral beings are continuous, not confined to a mythic past but active in the present through signs, ritual and landscape.

Illustrative Tales: The Emu Chase and the Gift of Water

Two narrative strands – one cosmological and one practical – exemplify the way Baiame stories combine explanatory power with ethical instruction. The story often referred to as the “Emu Chase” interweaves the creation of terrestrial features with observations of the night sky: a great emu flees across the earth, leaving marks that become waterholes, gorges and seasonal feeding grounds; the chase escalates into the heavens, where the emu’s form becomes visible in the dark spaces of the Milky Way while Baiame’s pursuit is marked by bright stars. Such a tale functions as an oral map that calibrates seasonal movement and resource use, as well as encoding rules for ceremony around hunting and totemic obligations.

Another common story recounts Baiame responding to drought. The people petition him through ritual; he shows an elder a site and strikes the ground with a sacred implement (a boomerang or digging stick), freeing an underground spring. He then instructs the community in ceremonies that maintain rain and water, handing down sequences of sound, movement and offering. These narratives teach not only that the environment is responsive to ritual, but that human action – guided by ancestral law – can reconfigure precarious conditions through disciplined practice.

Symbolism and Representation

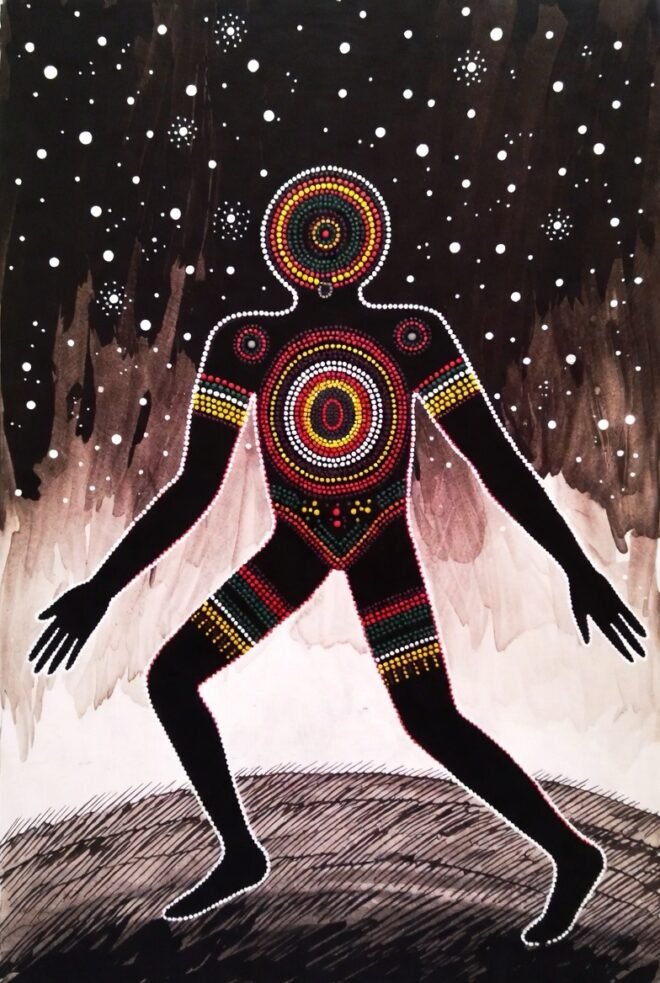

Baiame’s iconography and symbolic attributes vary with location and artistic modality, but several motifs recur. In rock art and shelter paintings attributed to Baiame’s presence, he is often shown as a large anthropomorphic figure with outstretched arms, sometimes haloed or signified by radiating lines. Footprints, concentric circles and animal forms frequently accompany these figures, creating a visual shorthand for a suite of stories tied to the specific site. These images operate as mnemonic devices and ceremonial prompts, embedding narrative cues into the landscape.

One motif associated with Baiame is the boomerang, which in narrative registers signifies return, justice and skill. Instruments associated with ceremony – digging sticks, coolamons, clapsticks – may also appear in iconography relating to Baiame, emphasising his role as teacher. In some recorded depictions, Baiame is shown without a mouth; this detail has interpretive variations across traditions. It may suggest silent authority, the ineffability of spiritual presence, or simply be an artistic convention distinct to certain regional schools of art.

Beyond rock art, contemporary Indigenous art and performance rework these motifs in media ranging from acrylic painting to sculpture and digital art. Artists both animate and critique ancestral themes, using Baiame’s image to assert identity, to educate, and to bridge traditional knowledge with contemporary political and environmental concerns. It is important to stress that the use of sacred imagery in public or commercial contexts is governed by cultural protocols, and many communities assert control over the reproduction of sacred symbols and the telling of certain stories.

Cultural Significance and the Role of Law

Baiame’s lasting cultural significance is closely bound to his function as a lawgiver. The social fabric in many southeastern communities – kinship moieties, marriage regulations, ceremonial responsibilities and totemic duties – are framed through ancestral instruction. These legal structures are not arbitrary: they mediate resource distribution, avoid genetic inbreeding, ensure the stewardship of species and sites, and delineate responsibilities across generations. In this way, Baiame’s laws are both spiritual ordinance and pragmatic governance.

Ceremonies that renew and teach these laws – bora initiations, corroborees, secret ritual assemblies – serve as institutional processes for transmitting knowledge, adjudicating disputes, and integrating new members into the social order. These practices create moral economies of reciprocity and obligation that have supported sustainable living over centuries. In modern contexts, elements of this traditional governance are being invoked in community-based land management, cultural education and health initiatives. For example, lessons embedded in Baiame’s injunctions about resource use can inform contemporary strategies like fire-stick farming (cultural burning), fish and waterway management, and biodiversity protection. Thus, ancestral law is not merely historical; it is adaptable, operative and relevant to contemporary ecological crises.

Comparisons with Other Creator Beings

Situating Baiame in a comparative indigenous cosmology highlights both shared themes and region-specific distinctiveness. In the Kimberley region of northwestern Australia, Wandjina figures function as cloud and rain beings; their stylised, mouthless faces painted on cave walls are potent regulatory presences in rainmaking and weather law. While Baiame and the Wandjina share roles in controlling weather and upholding law, the Wandjina corpus tends to emphasise a more localised, pictorial, rainfall-focused rituality, whereas Baiame is often narrated in terms that foreground sky-father authority and the establishment of regional-wide social systems.

The Rainbow Serpent – one of the most widely disseminated ancestral beings across Australia – shares with Baiame the role of creating country and regulating water, but differs in form and emphasis. The Serpent’s mythic actions include digging riverbeds and participating in cycles of destruction and renewal; it is sometimes ambivalent, both life-giving and fearful. Baiame’s portrayal is generally more paternal and law-oriented, emphasising instruction and social order.

Bunjil – the creator and eagle ancestor among the Kulin peoples of Victoria – presents another instructive parallel. Bunjil is often depicted as an eagle and is associated with law, creation and the ascent to the sky after establishing cosmic order. The thematic overlap with Baiame is strong in terms of lawgiving and the sky-as-home motif, though local narratives, ritual forms and iconography differ across country. Across these examples, a shared pattern emerges: creator-beings mediate the relationship between people and country, providing the ethical and practical frameworks for life in particular landscapes.

Modern Relevance, Revitalization and Protection

Baiame’s stories and associated sites have become focal points in contemporary cultural revitalisation, land claims and environmental advocacy. Protected sites such as rock art shelters attract scholarly attention and tourism, yet this creates a need for sensitive custodial approaches that foreground Indigenous authority. Indigenous-led cultural tours, interpretive programs and educational partnerships have been effective in enabling public access while asserting control over narratives and appropriate practices.

Legal and political mechanisms – Native Title claims, heritage listings, and cultural heritage protection laws – have provided avenues for communities to reclaim stewardship of ancestral lands and to control the use of sacred imagery. At the same time, misuse or appropriation of sacred themes by non-Indigenous entities remains an ongoing concern; many communities actively negotiate or litigate to protect their cultural intellectual property and to prevent disrespectful commercialisation.

Baiame’s symbolism has been productively integrated into contemporary projects addressing environmental and social well-being. Programs that blend traditional ecological knowledge with Western ecological science draw upon ancestral laws to inform fire management, waterway rehabilitation and species protection. Cultural education initiatives in schools use stories of Baiame and associated cosmologies to teach astronomy, seasonal cycles and ecology, thereby creating culturally relevant pathways for STEM learning for Indigenous students.

The restorative power of cultural reconnection is also notable. As Indigenous communities work to rebuild language, ceremony and custodial systems disrupted by colonisation, stories of Baiame provide cohesion, identity and spiritual support. Elders who transmit these narratives and rituals perform an essential role in healing intergenerational trauma and in fostering collective resilience.

Ethical Considerations and Cultural Protocol

It is important to end with an explicit note on ethics. Aboriginal cosmologies include layers of knowledge: some stories and images are public, while others are strictly restricted to initiated persons or certain kin groups. The recounting above draws predominantly on elements that have been publicly recorded and discussed in scholarly and community-accessible contexts. However, readers should be mindful that many aspects of Baiame-related practice and lore remain culturally sensitive and are subject to protocol. Respect for Indigenous custodianship means that visitors to sacred sites should seek permission, observe local guidance, and avoid commercial exploitation of sacred motifs. Non-Indigenous artists, researchers and institutions should work in genuine partnership with custodial communities and ensure appropriate recognition, benefit-sharing and cultural safety.

Conclusion

Baiame remains a profound symbol of creation, law, and relational responsibility in southeastern Australian Indigenous traditions. His narratives encode cosmological insight, ecological knowledge and social governance; they bind people to place, to one another, and to ongoing obligations of care. As the contemporary moment compels renewed attention to Indigenous knowledge systems – both for their cultural value and for their practical contributions to land and sea management – Baiame’s stories offer lessons in humility, reciprocity and long-term stewardship.

The enduring power of Baiame lies not in static preservation but in living practice. Ceremonies, rock art, stories and family memory keep these traditions animate, allowing each generation to interpret and reapply ancestral law in ways responsive to present conditions. When modern education, cultural policy and environmental practice engage with Aboriginal custodians on terms that respect cultural integrity, they open pathways for mutual learning and shared stewardship. In that collaborative space, the figure of Baiame functions as both teacher and reminder: that human flourishing depends upon ethical relations with the land, with others, and with the ancient forces that shaped the world.

If you engage with Baiame’s sites, stories or images, do so with curiosity tempered by respect. Seek guidance from local custodians, support Indigenous-led programs, and consider how the principles encoded in these traditions – care for country, balanced reciprocity, intergenerational responsibility – might inform how we live together on this land.

Acknowledgment

In producing this account I acknowledge that the information about Baiame has been preserved and transmitted by Aboriginal custodians across generations. This essay draws on publicly available ethnographic records and contemporary community work; however, it is not a substitute for learning from living custodians and Elders. Readers are encouraged to seek out Indigenous voices, support community-led cultural initiatives, and approach these traditions as ongoing, living knowledges that deserve care and protection.