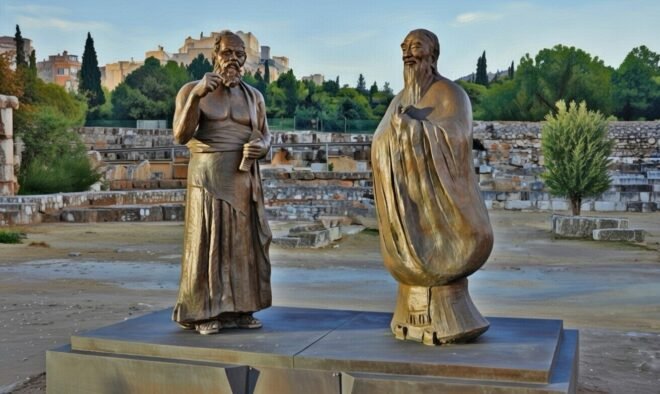

The bronze figures of Socrates and Confucius standing together in the ancient agora of Athens evoke an image at once arresting and oddly fitting: two emblematic thinkers from distinct civilisational traditions, posed in bronze as if engaged in conversation across the centuries. The sculpture by Wu Weishan, unveiled as part of a cultural exchange initiative, invites us to imagine encounters that history would not have permitted. Yet the image also prompts a deeper, more consequential question: which historical interlocutor might have offered Socrates the most illuminating exchange on the shared moral dilemmas of their era and ours? In seeking to answer that question, it becomes clear that Gotama the Buddha offers a more compelling counterpart to the Athenian gadfly than Confucius does. This essay sets out to reconstruct a dialogue between Socratic and Buddhist orientations, to explore the convergences and divergences of their ethical emphases and methods of inquiry, and to argue that engaging simultaneously with Greek and Buddhist thought can enrich our responses to present global crises.

Socrates and Gotama were contemporaries in the broadest sense, flourishing in the tumultuous centuries that historians have often identified as the Axial Age. While the geographical distance between northeast India and the polis of Athens, and the political barriers of the Persian Empire, precluded any direct contact, the two men confronted remarkably similar questions: how should one live; what constitutes flourishing life; how can persons become morally autonomous in the midst of social instability and ritualised tradition? Both thinkers prioritised ethical concern and self-examination, eschewed merely ritualistic adherence to inherited custom, and sought methods to awaken persons from moral complacency. Yet they differed in the contours of their metaphysical frameworks, pedagogical aims, and institutional legacies, distinctions that make the comparative exercise both revealing and practically significant.

Socratic practice is best understood as an ethic of critical interrogation. Socrates, as he appears in the earliest accounts, pursued definitions of virtues such as justice, courage, and piety through conversational questioning. The elenchus, or refutation, aimed less at delivering fixed doctrines than at exposing contradiction, intellectual complacency, and unexamined assumption. For Socrates, to live unexamined is to live poorly; moral knowledge requires self-scrutiny and an orientation toward the examined life. This practice presupposes a high regard for reasoned dialogue and a belief in the possibility that persistent questioning can yield ethical clarity or at least a more defensible stance. Socrates’ life in the Athenian polis – indicted and ultimately executed on charges connected to impiety and corrupting the youth – signals the high political stakes of relentless questioning in a community whose identity depends on contested traditions and civic rituals.

Gotama the Buddha emerges from the Indian context as a teacher of liberation who frames ethical inquiry within a diagnostic model of suffering. His first sermon set forth the Four Noble Truths, a schematic that diagnoses dukkha – variously translated as suffering, unsatisfactoriness, or existential unease – identifies its causes in craving and ignorance, proposes the cessation of suffering as a feasible goal, and prescribes a path of ethical conduct, mental cultivation, and wisdom. Where Socrates foregrounds a dialectical search for definitions and ethical clarity, Gotama situates ethical practice within an integrated path that transforms perception, intention, and attention. The Buddhist path is not merely cognitive in the sense of stimulating argument; it is therapeutic and transformative, designed to eradicate the afflictive conditions of mind that produce harmful behaviours and cyclical rebirth.

Despite these methodological divergences, Socratic and Buddhist emphases intersect powerfully around the primacy of ethics and the cultivation of autonomy. Both traditions place responsibility on the individual to interrogate their inherited beliefs and to become ethically self-directed. Socrates’ relentless questioning seeks to dismantle false confidence in conventional wisdom; Gotama’s meditative and moral training aims to dissolve the illusions of self and craving that underwrite harmful attachment. Each tradition thus cultivates a kind of freedom: Socrates offers intellectual autonomy and moral accountability within the public arena of dialogue; the Buddha offers an existential release from the loops of desire and aversion through inner cultivation. Each, in its way, seeks to awake people from forms of unreflective living.

Understanding these affinities opens a productive space for considering how their teachings might illuminate contemporary problems: a global pandemic, entrenched political polarisation, ecological crisis, and the moral perplexities of technological life. Modernity’s challenges are global in scope and demand intellectual and moral resources that can reach beyond parochial frames. Those resources may be found, in part, by refusing the binary of East versus West and by engaging in a creative synthesis that honours the distinctiveness of each tradition while seeking their mutual enrichment. The comparative study of Socrates and the Buddha is not an exercise in cultural equivalence; it is an invitation to cultivate conceptual pluralism and moral imagination that can respond to the demands of an interconnected world.

To make this case concrete, one may begin with the nature and aim of ethical inquiry. Socrates’ method trusted dialogical exchange and dialectical reason as means to unsettle complacent opinion. In a democracy such as Athens, the agora was a forum where citizens debated the form and aims of the commonwealth. Socrates’ practice exemplifies civic-mindedness: the examined life is a contribution to the polis, a form of political education that holds leaders and fellow citizens to rational accountability. On the Buddhist side, ethical inquiry is deeply experiential; it is verified through transformation in character and mental clarity, not merely through logical consistency. The Buddha’s approach recognises the limits of discursive reasoning to cure suffering when clinging and self-centredness persist at the level of perceptual and affective habits. Therefore, the Buddhist path integrates ethical conduct (sila), concentration (samadhi), and wisdom (panna) as mutually reinforcing capacities.

The possibility of bringing these approaches into conversation has practical implications. Consider the ethical challenges posed by a global health crisis. Socratic questioning can illuminate public rationales, expose contradictions in policy, and encourage civic accountability. It can force citizens and leaders to articulate reasons for measures that curtail liberties or distribute resources unevenly. Socratic engagement demands that such decisions be subject to reasoned defence and moral scrutiny. Buddhist practice, on the other hand, offers therapeutic tools for coping with collective fear and grief. Mindfulness and compassion-based practices cultivate equanimity, reduce anxiety, and encourage attention to shared vulnerability. These practices foster a communal ethic of care that can motivate compliance with public health measures for the sake of others rather than through coercion alone. Together, such resources promote both responsible public discourse and the inner qualities necessary for enduring crisis.

The philosophical differences between these thinkers also bear on questions of metaphysics and selfhood that shape moral perspectives. Socratic thought, as preserved in Platonic dialogues and other sources, is compatible with a view of the person as a rational agent whose moral identity is constituted by reason-guided choices. The Buddhist critique of self, by contrast, contends that what we call the self is a transient aggregation of processes and phenomena, lacking a permanent, unchanging essence. This philosophical divergence has ethical consequences. If the self is not a simple enduring entity, then moral responsibility must be understood in terms of interdependent processes and causal conditioning. Buddhist ethics emphasises the relational and conditioned nature of actions: intentions arise in a web of mental and social causes and have consequences that reverberate through that web. Socratic ethics, though not committed to a static notion of self, tends to presume a stable subject capable of reflective self-control through reason. A synthesis of the two views can enrich moral psychology by combining the prescriptive clarity of Socratic deliberation with the therapeutic insights of Buddhist analyses of cognition and attachment.

The institutional outcomes of these philosophies further reveal complementary strengths. Socratic practice, manifested in the rhetorical and pedagogical traditions of Western thought, cultivated an ethos of public reasoning and critical scrutiny that has undergirded many democratic institutions. The commitment to public accountability, debate, and legal structures of justice has clear roots in Socratic and post-Socratic Greek political life. Buddhist institutionalisation, by contrast, produced monastic communities that embodied a disciplined ethic of renunciation, systematic training in meditation, and codified rules aimed at communal harmony and moral cultivation. Buddhist institutions preserved teachings and provided stable environments for sustained practice across generations. Both patterns are instructive for contemporary societies: we need resilient public spheres capable of reasoned debate, and we also need institutions and practices that support ongoing moral and psychological formation.

Yet the comparative task must resist anachronistic projections. It is tempting to extract an antidote from antiquity and claim that the combined wisdom of Socrates and the Buddha would straightforwardly solve modern problems. History and philosophy caution against such facile optimism. Both traditions emerged in particular social, economic, and cultural circumstances. Their teachings must be read attentively, resisting the temptation to universalise without transformation. That is precisely why a synthetic approach must be hermeneutic as well as critical: it seeks to translate rather than transplant, to render ancient insights intelligible in new contexts without erasing their specificity.

This nuanced approach to comparative philosophy can be pursued through several interrelated strategies. First, scholars and public intellectuals can develop interpretive frameworks that highlight the procedural affinities between Socratic dialogue and Buddhist methods of inquiry. Both traditions prize a disciplined attention to the processes by which beliefs are formed and sustained. Second, educators can incorporate comparative modules into curricula that do not treat traditions as isolated artefacts but as living resources for ethical and civic formation. Third, institutions devoted to public life might cultivate practices derived from both traditions: public forums that integrate critical questioning with practices of empathy and contemplative listening could foster deliberative spaces suited to a polarised age.

At the level of lived practice, individuals can sample and synthesise methods in ways that respect their original aims. One might adopt Socratic-style questioning in public debate while cultivating Buddhist-inspired practices of attention to reduce reactivity and promote genuine listening. The two practices, when combined, could facilitate civic exchange that is simultaneously rigorous and compassionate. In polarised political contexts, such integrated practices could make it possible to critique ideas without demonising their bearers and to address systemic injustices without succumbing to nihilistic despair.

A comparative perspective also sheds light on the nature of moral authority and how societies might legitimate ethical claims. Socrates famously refused to appeal to an external religious authority in defence of his positions; his authority derived from the convincingness of his argument and his moral example. The Buddha similarly taught not by invoking canonical mandates but by inviting verification through practice: test the teachings in your own experience. Both models converge on a principle of ethical autonomy that refuses to defer final moral authority to tradition or external decree. This shared emphasis has profound implications for contemporary discourse. In pluralistic societies, appeals to absolute doctrinal truth are unlikely to be persuasive across difference. Ethical claims grounded in reasoned argument and verifiable experiences of transformation are more likely to gain cross-cultural traction.

Moreover, engaging both traditions compels us to confront the ethical implications of power and social structure. Socratic critique targets complacent elites, sophistry, and the unexamined assumptions underpinning political life. Buddhist analysis highlights how greed, hatred, and delusion are not merely individual defects but are shaped and encouraged by social arrangements. The integration of these perspectives encourages a diagnosis of social ills that is both analytic and transformative: it insists on scrutiny of norms while recognising the need to alter the conditions that perpetuate suffering. Political reform, from this vantage, is insufficient without cultural and psychological change, and individual moral cultivation is insufficient without structural transformation.

The contemporary relevance of this comparative inquiry becomes most urgent in the face of ecological crisis. The planetary environmental emergency prompts questions about the moral status of nonhuman life, the distribution of resources, and the temporal horizons within which ethical decisions are made. Socratic deliberation is invaluable for clarifying principles of justice and stewardship and for designing collective agreements about resource use. Buddhist ethics, with its emphasis on interdependence and compassion, supplies a moral imagination that extends moral concern beyond human self-interest to embrace a broader sense of kinship with sentient life. A synthesis encourages policy frameworks that are informed by rigorous public reasoning and animated by a widened ethical concern that includes future generations and nonhuman beings.

The pedagogical implications of combining Socratic and Buddhist approaches are also profound. Education must cultivate both critical intelligence and capacities for inner regulation. The cultivation of attention, empathy, and equanimity is not a luxury; it is a necessary precondition for citizens to engage responsibly in complex public deliberation. Schools and universities can experiment with curricula that interweave dialectical inquiry, moral philosophy, and contemplative practice to produce graduates prepared for the cognitive, emotional, and ethical demands of globalised life.

Of course, creative synthesis invites criticism from multiple quarters. Some might argue that Socratic emphasis on public reason risks neglecting the inner work required to sustain ethical dispositions, while others may worry that Buddhist inwardness could supply a quietist escape from political responsibility. These critiques have merit insofar as they point to potential imbalances. The productive task, then, is not to fuse traditions indiscriminately but to calibrate their contributions so that critical public engagement is matched by inner discipline and compassionate imagination.

This calibration requires intellectual humility and historical sensitivity. To draw fruitfully from Socrates and the Buddha, contemporary readers must resist using either as ideological instruments for present agendas. Instead, the aim should be reflective appropriation: taking up practices and insights in ways that honour their contexts while making them responsive to current needs. Such a responsible appropriation might, for example, adopt Socratic questioning to refine public policy while deploying Buddhist-informed compassion to ensure that policies aim not merely at efficiency but at alleviating suffering and cultivating human dignity.

A final dimension of this comparative project concerns the cultivation of moral exemplars. Both Socrates and the Buddha fashioned lives that were pedagogically powerful. Socrates’ fearless commitment to philosophical inquiry, even in the face of death, taught about the costs and rewards of intellectual integrity. The Buddha’s renunciation and subsequent life of teaching embodied a pathway toward liberation from suffering. Contemporary societies seldom produce moral exemplars whose lives can be plausibly emulated at scale. Nevertheless, rearticulating the virtues exemplified by these figures – courage in critique, humility in inquiry, compassion in action, and steadfast practice – can help restore a moral grammar that guides both public and private life.

In conclusion, the imagined encounter between Socrates and Confucius in a modern agora invites us to ask whether other meetings of minds might yield richer resources for our time. The comparative engagement with Socrates and Gotama the Buddha reveals both convergent emphases on ethical autonomy and critical self-examination and divergent commitments to method, metaphysics, and institutional forms of moral training. Neither tradition alone suffices to redeem the complex moral and political challenges we face in a globalised and technologically saturated world. Yet together they offer a complementary toolkit: Socratic dialectic supports public reasoning and accountability; Buddhist practice cultivates inner transformation and an expansive ethic of care.

Responding to our present crises requires the courage to move beyond the comfortable binaries of East and West, tradition and innovation, reason and feeling. It requires a willingness to translate ancient resources into contemporary forms of life that are attentive to empirical realities and to the depths of human experience. Above all, it demands an imaginative moral cosmopolitanism that can hold in tension the disciplined inquiry of Socrates and the compassionate, liberative orientation of the Buddha. If we can learn to listen to both voices – not to subsume one in the other but to let each test and enrich the other – we may find ourselves better equipped to ask the difficult questions anew and to act with wisdom and compassion in the face of an uncertain future.