Australia Day, observed annually on January 26, commemorates the arrival of the First Fleet in Sydney Cove in 1788. This date symbolises the inception of European settlement in Australia, a moment that stirs national pride for many, evoking images of a burgeoning nation built on exploration and resilience. However, for Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples, it is often regarded as Invasion Day – a stark reminder of colonisation, dispossession, and cultural upheaval. As we approach Australia Day in 2026, it is imperative to reflect on this duality, centring the voices and experiences of Indigenous Australians. Indigenous perspectives, such as those articulated by Aboriginal activists, frame the day as a celebration of one culture’s arrival at the expense of another’s, highlighting the profound loss endured by First Nations peoples. This essay draws upon “The Art of the First Fleet & Other Early Australian Drawings”, edited by Bernard Smith and Alwyne Wheeler and published in 1988 by Yale University Press in association with the British Museum (Natural History) and the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art. This comprehensive volume reproduces over 250 previously unpublished illustrations selected from more than 600 drawings and paintings of Australian subjects held in the British Museum (Natural History). These artworks, created by artists aboard the First Fleet and during the early years of settlement, offer invaluable insights into the physical appearance, daily activities, social structures, cultural practices, and initial interactions of the Eora people with the newcomers.

The First Fleet, commanded by Captain Arthur Phillip, consisted of 11 ships carrying approximately 1,400 individuals, including convicts, marines, officers, and their families. Departing from Portsmouth, England, in May 1787, the fleet endured an eight-month voyage fraught with challenges before arriving at Port Jackson, now known as Sydney Harbour. Upon arrival, the British encountered the Eora nation, a confederation of clans including the Cadigal, Wangal, Cammeraygal, Dharawal, Dharug, and Kurringgai, who had inhabited the Sydney Basin for tens of thousands of years. The artists among the fleet – primarily amateurs influenced by Enlightenment ideals of scientific observation and natural history – documented their impressions through watercolours, inks, pencil sketches, and other media. Key contributors include the anonymous artist dubbed the “Port Jackson Painter,” midshipman George Raper from the HMS Sirius, and Thomas Watling, a convicted forger transported for his crimes. The book organises these works into thematic sections, with scholarly chapters providing context: R. J. Lampert discusses the ethnographical significance, T. M. Perry analyses charts and views of Sydney, Alan Frost relates the drawings to the settlement process, J. H. Calaby examines natural history illustrations, and Bernard Smith explores their art-historical importance.

This essay explores Aboriginal society as portrayed in these artworks, delving into the Eora’s physical and cultural world, economic practices, social organisation, spiritual beliefs, and transformative encounters with the British. While the drawings are inherently Eurocentric, often framing Indigenous people through lenses of curiosity, exoticism, or the “noble savage” trope, they inadvertently preserve elements of a sophisticated, adaptive society deeply connected to the land. These visual records counter the colonial myth of “terra nullius,” the legal fiction that deemed Australia unoccupied and available for seizure. Instead, they depict a populated, managed landscape teeming with life and human activity. On Australia Day 2026, reflecting on these images encourages a national conversation about reconciliation, truth-telling, and recognition of First Nations sovereignty. By examining the Eora through the First Fleet’s artistic lens, we honour their resilience and challenge historical erasures.

Historical Context of the First Encounter

The arrival of the First Fleet on January 26, 1788, was not an act of discovery, but an intrusion into a thriving Indigenous world that had evolved over more than 65,000 years. The Eora people, traditional custodians of the Sydney region, had developed a complex society sustained by the abundant resources of the coastal environment, including harbours, rivers, forests, and wetlands. Their knowledge of the land – encompassing seasonal migrations, resource management, and spiritual connections – was profound, allowing them to thrive in harmony with nature. The fleet’s initial attempt to settle at Botany Bay, based on Captain James Cook’s 1770 observations, failed due to inadequate water and soil, leading to the relocation to Port Jackson. This move brought the British directly into Eora territory, where the Indigenous inhabitants observed the massive ships with a mixture of intrigue and wariness.

Journals from the fleet, such as those by Lieutenant Watkin Tench and Judge-Advocate David Collins, provide textual accounts of these initial meetings, describing exchanges of goods, gestures of friendship, and occasional misunderstandings. However, the visual records in “The Art of the First Fleet” offer tangible, immediate evidence of the encounters. George Raper’s topographical drawings, for instance, integrate Aboriginal figures into the landscape, portraying them not as intruders, but as essential components of the ecosystem. One such work depicts Eora men in slender bark canoes gliding across the harbour, their paddles dipping rhythmically into the water, highlighting their unparalleled maritime skills and intimate knowledge of currents, winds, and marine life. These canoes, crafted from stringybark trees and sealed with resin, were versatile vessels used for fishing, transportation, and trade between clans.

The Port Jackson Painter’s ethnographic studies capture the raw energy of first contacts. In these sketches, Eora individuals approach the British ships, their bodies adorned with white clay markings, extending hands in gestures that could signify welcome, curiosity, or assessment. Lampert’s chapter in the book emphasises the ethnographical value of these images, noting how they document Aboriginal customs, tools, and social interactions with a level of detail absent from written records. The Eora society was semi-nomadic, with clans of 20 to 50 people moving seasonally between coastal sites rich in seafood during summer and inland areas for hunting in winter. Drawings illustrate this mobility through depictions of temporary campsites featuring gunyahs – shelters constructed from branches, bark, and leaves – arranged in family clusters around central fire hearths. These scenes reveal a society organised around kinship ties, where extended families formed the basic social unit, sharing resources and responsibilities.

Thomas Watling’s contributions, which form a substantial portion of the book’s plates, include vivid scenes of Aboriginal people engaged in food gathering, underscoring their hunter-gatherer economy. Watling, despite his status as a convict, produced a diverse body of work ranging from topographical views to detailed studies of Indigenous life. His drawings counter the European perception of an empty land by showing a densely inhabited, actively managed environment. For example, illustrations of controlled burns – fires set to regenerate vegetation and attract game – demonstrate the Eora’s sophisticated land management practices, now recognised as “fire-stick farming.” Calaby’s analysis in the book links these human activities to the natural history drawings, illustrating how Aboriginal people interacted with endemic species like kangaroos, wallabies, emus, and various fish, which were novelties to the Europeans.

Culturally, the Eora were embedded in a network of kinship systems governed by lore – unwritten laws passed through oral traditions, songlines, ceremonies, and Dreamtime stories. While the artists lacked the cultural context to fully comprehend these elements, their sketches hint at their richness. Recurring motifs include body paint and cicatrisation (scarification), which Lampert identifies as markers of initiation, status, and totemic affiliations. Applied using red ochre, white clay, and charcoal, these decorations signified social roles, spiritual connections, and participation in rituals. The drawings also capture gender divisions in labour: men are often shown hunting with spears launched via woomeras (spear-throwers) or boomerangs, while women appear fishing with lines or caring for children, reflecting a complementary and balanced system where both genders contributed equally to survival.

The initial encounters between the Eora and the British were characterised by mutual curiosity and tentative exchanges. Artworks depict Eora people examining European artefacts like metal hatchets, beads, and clothing, often trading fish or other items in return. These bartering scenes suggest an early attempt at cross-cultural communication, with the Eora demonstrating openness to novelty while asserting their territorial rights. However, tensions emerged swiftly, as illustrated in drawings of confrontations, such as the spearing of Governor Phillip in September 1790 at Manly Cove. Raper’s rendering of this incident shows an Eora warrior hurling a spear, symbolising resistance to encroachment on fishing grounds and resources. The book highlights that these artworks, produced in the colony’s formative years (1788–1792), capture a fleeting period of relative equilibrium before introduced diseases, particularly smallpox in 1789, ravaged the Eora population. Estimates suggest the Sydney region’s Indigenous population dropped from around 1,500 to mere hundreds within a few years, a demographic catastrophe that altered the social fabric irreversibly.

Through these visual narratives, “The Art of the First Fleet” underscores the Eora’s agency and dignity. Unlike later colonial art that often marginalised or romanticised Indigenous people, these early drawings portray them as confident, statuesque figures equal in presence to the Europeans. Frost’s chapter contextualises this within the settlement’s challenges, including food shortages and labour issues, but the artworks reveal the Eora as knowledgeable guides who initially assisted the colonists with local resources. This historical context provides a foundation for understanding the multifaceted nature of Aboriginal society as documented in the art, setting the stage for a deeper examination of its various dimensions.

Depictions of Physical Appearance and Portraits

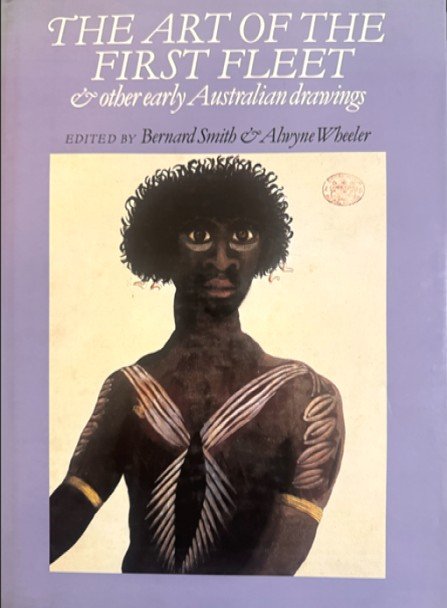

One of the most compelling aspects of “The Art of the First Fleet” is its collection of the earliest European portraits of Australian Aboriginal people, offering detailed studies of their physical features, adornments, and expressions. These images, primarily by the Port Jackson Painter and Thomas Watling, provide a window into the Eora’s aesthetic and cultural identity, though filtered through European artistic conventions influenced by Enlightenment portraiture.

The book features numerous full-face and profile portraits, rendered with a precision that reflects the artists’ observational skills. Watling’s sketches, for example, depict Eora men with strong, angular faces, dark brown skin tones, and thick, curly hair often styled with animal fat, feathers, or bone ornaments. Scarification – raised keloid scars resulting from ritual incisions – is a prominent feature, symbolising rites of passage, clan membership, and personal achievements. Lampert explains that these scars, along with the avulsion of front teeth during initiation ceremonies, served as badges of honour, marking the transition from youth to adulthood and eligibility for marriage or leadership roles. Women are portrayed with similar facial structures, but frequently shown with practical accessories like dilly bags (woven string bags) slung over their shoulders or infants cradled in their arms, emphasising their roles in gathering and child-rearing.

A standout plate is the Port Jackson Painter’s “Aboriginal Man with Spear and Shield,” which captures a warrior in a poised, alert stance, his body decorated with intricate white pipeclay designs. These patterns, applied for corroborees (ceremonial dances and gatherings), reveal the Eora’s artistic expression through body art, a practice deeply tied to storytelling, spiritual invocation, and social cohesion. The book’s commentary notes that while European artists, unfamiliar with these customs, occasionally exaggerated features to align with notions of the “exotic” or “primitive,” the accuracy in depicting tools – such as the multi-pronged fishing spear (fizgig) or the parrying shield (hielaman) – demonstrates meticulous observation. Such details highlight the Eora’s technological ingenuity, with weapons and implements crafted from local materials like hardwood, stone, and sinew.

Clothing in the drawings is minimal, adapted to the temperate climate of the Sydney region. In warmer scenes, figures appear naked or with modesty aprons made from animal skins or woven grass, while cooler weather depictions include possum-skin cloaks draped over shoulders for warmth. Adornments like shell necklaces, nose bones (pierced through the septum), and armbands indicate personal decoration, status, and participation in trade networks that extended beyond the Eora territories. Raper’s group portraits showcase variations in age and social standing, from bearded elders exuding authority to lithe youths in the prime of life. These images suggest a society with subtle hierarchies based on accumulated knowledge, experience, and spiritual wisdom, where elders acted as custodians of lore, mediators in disputes, and teachers of traditions.

The portraits also convey a range of emotions, adding humanity to the subjects. Curiosity is evident in wide-eyed gazes toward European objects, wariness in slightly furrowed brows during encounters, and dignity in direct, unflinching stares that challenge the viewer’s gaze. In one Watling drawing, an Eora man looks straight out from the page, his expression composed and resolute, as if asserting his sovereignty amid the colonial intrusion. Bernard Smith’s final chapter argues that these works initiate a cross-cultural dialogue in art, blending European techniques with Indigenous subjects to form the genesis of Australian visual culture. Despite biases, these depictions humanise the Eora, countering dehumanising colonial narratives and affirming their physical resilience, cultural pride, and individuality. They serve as a poignant reminder of the people behind the historical events, whose features and forms were captured in a moment of profound change.

Expanding on these portraits, the book reveals how physical appearance was intertwined with cultural identity. Body modifications, such as scarification, were not merely decorative but narrative devices, encoding personal histories, totemic relationships, and social affiliations. For instance, specific patterns might represent a clan’s connection to a particular animal or landscape feature, reinforcing the Eora’s holistic worldview where humans, nature, and spirits were interconnected. The artists’ focus on these elements, though sometimes sensationalised, preserves visual evidence of practices that were later suppressed or lost due to colonial policies. In reflecting on these images today, we can appreciate the Eora’s beauty standards, which prioritised harmony with the environment over European ideals of attire or ornamentation. This section of the book, rich with over 100 ethnographic plates, underscores the diversity within Eora society, from coastal fishers to inland hunters, each adapted to their niche yet united by shared cultural threads.

Daily Life and Activities

The artworks in “The Art of the First Fleet” vividly illustrate the Eora’s daily life, showcasing a sustainable economy rooted in hunting, gathering, fishing, and environmental stewardship. These scenes, drawn from direct observations in Port Jackson, reveal a society in perfect equilibrium with its surroundings, employing sophisticated tools and seasonal strategies to ensure abundance.

Fishing emerges as a dominant theme, given the harbours bounty of marine resources. The Port Jackson Painter’s “Native Going to Fish with a Torch and Flambeaux” depicts a man wading through shallow waters at night, holding a flaming torch to attract fish, while his family tends a fire on the shore, broiling the catch. This image highlights communal meals and gendered labour divisions: men often engaged in spear-fishing using barbed prongs or gigs, while women and children used handlines with shell hooks or gathered shellfish from rock pools. The book details the construction of bark canoes (nowie), stripped from eucalyptus trees, shaped with fire, and bound with vines, demonstrating engineering prowess that allowed navigation of rough waters. Watling’s sketches show women fishing from these canoes, their techniques sustainable and attuned to tidal cycles, ensuring resources were not depleted.

Hunting activities are captured in dynamic scenes, illustrating the Eora’s skill with weapons like boomerangs, clubs (nulla-nullas), and spears. Raper’s drawings depict men stalking kangaroos or wallabies, using stealth and tracking knowledge passed down generations. The use of fire in hunting is notable; controlled burns cleared undergrowth, promoted grass growth, and flushed out game, a practice that maintained biodiversity and prevented large wildfires. Gathering is portrayed in subtler images, with women using digging sticks (wana) to unearth yams, roots, and tubers, or collecting honey from native bees, berries from lilly pillies, or oysters from mangroves. These activities emphasise the Eora’s encyclopaedic knowledge of edible plants and seasonal availability, with diets rich in proteins, vitamins, and fibres.

Shelter and campsite arrangements reflect a mobile lifestyle. Gunyahs, dome-shaped huts framed with saplings and covered in bark or grass, are shown in family groupings, suggesting kin-based organisation where resources were shared equitably. Fire hearths served as social hubs for cooking, storytelling, and warmth, with drawings capturing the glow of embers against twilight skies. Lampert’s ethnographical analysis highlights how these illustrations document seasonal movements: summer camps along the coast for seafood feasts, winter relocations inland for hunting possums and echidnas. Tools like stone axes (for chopping wood), grinding stones (for processing seeds), and baskets (for carrying) reflect a material culture honed over millennia, with trade in items like ochre, shells, and stone tools indicating inter-clan networks extending to neighbouring groups like the Dharug or Gandangara.

These daily life depictions underscore the Eora’s self-sufficiency and deep environmental ethic. Unlike the British, who struggled with unfamiliar terrain and relied on imported supplies, the Eora lived abundantly, with no concept of famine in their lore. The artists’ fascination with “peculiar” methods, such as climbing trees using toe-holds cut with axes to catch possums or using fishbone barbs for hooks, reveals European ethnocentrism but also preserves Indigenous ingenuity. Calaby’s chapter connects these human activities to natural history, showing how the Eora’s practices influenced the ecosystem, such as through selective harvesting that promoted species diversity. In essence, the artworks portray a balanced, rhythmic existence disrupted by colonisation, where daily routines were infused with cultural significance, from thanking spirits for a successful hunt to sharing stories around the fire.

To further elaborate, consider the role of children in daily life, as glimpsed in the drawings. Young Eora are shown learning skills through imitation – boys practicing spear-throwing with miniature weapons, girls weaving baskets under maternal guidance. This informal education ensured the transmission of knowledge, fostering resilience and adaptability. Seasonal festivals, hinted at in group scenes, involved feasting on abundant resources like flying foxes or mullet runs, strengthening social bonds. The book’s plates also capture moments of leisure, such as playing games with balls made from possum fur or swimming in the harbour, revealing a society that valued joy and community amid survival demands. These details paint a picture of a vibrant, holistic lifestyle, where work and play intertwined with spiritual reverence for the land.

Social Structure and Culture

Aboriginal society, as glimpsed through the First Fleet art, was structured around kinship, lore, and spirituality, forming a cohesive framework that governed behaviour, relationships, and interactions with the environment. The drawings hint at these elements through ceremonial scenes and group compositions, though the artists’ limited exposure constrains the depth.

Family units were the cornerstone, with images showing nuclear and extended families in domestic settings. Watling’s works depict multi-generational groups, with elders revered as repositories of knowledge, guiding younger members in lore and customs. Clans, typically 20-50 individuals linked by descent and totems, are implied in campsite layouts, where spatial arrangements reflected kinship rules, such as avoidance between certain relatives. Totemic relationships – affiliations with animals, plants, or natural phenomena – guided resource use, marriage, and rituals, ensuring ecological balance and social harmony.

Ceremonial life is evoked in sketches of corroborees, where figures dance in synchronised movements, accompanied by clapping sticks, bullroarers, and early forms of didgeridoos. Body paint in these drawings symbolises Dreamtime narratives, connecting participants to ancestral beings who shaped the land. Lampert discusses how initiation rites, evidenced by scarred bodies and missing teeth, reinforced social bonds, instilled discipline, and enforced lore – rules covering everything from hunting taboos to conflict resolution. These ceremonies were communal events, fostering unity across clans and marking life stages.

Spiritual beliefs permeate the artworks, though subtly. Depictions of burial practices, such as tree platforms or ground interments, suggest reverence for the dead and beliefs in an afterlife. Sacred sites, like rock engravings or ceremonial grounds, are inferred from harmonious integrations of people and landscape. The Eora’s concept of Country – as a living entity encompassing land, water, sky, and spirits – is evident in the respectful portrayal of interactions with nature. Gender roles appear balanced: men led in hunting and warfare, women in gathering and healing, with both participating in decision-making through consensus.

These elements reveal a society governed by reciprocity, where sharing was obligatory, and disputes resolved through mediation rather than hierarchy. Contrasting European authoritarianism, Eora governance was egalitarian, with authority derived from wisdom rather than power. The book’s analysis challenges colonial myths of primitivism, presenting a cultured, orderly society. Expanding this, lore functioned as a legal and moral code, with songlines mapping territories and histories, preserving knowledge orally. Artworks capturing storytelling around fires suggest rich narratives explaining creation, morality, and survival. Women’s roles extended to midwifery and medicine, using bush remedies like eucalyptus for ailments. Overall, the drawings illuminate a resilient cultural framework that endured despite colonial pressures.

Interactions with Europeans

The drawings chronicle the evolution from curiosity to conflict in Eora-British interactions. Initial scenes show bartering: Eora offering fish, oysters, or artefacts for metal tools, hats, or tobacco. These exchanges reflect mutual interest, with Aboriginal people quickly appreciating iron’s durability.

However, as settlement expanded, tensions mounted. Illustrations of spear-throwing incidents, like Phillip’s wounding, symbolise clashes over resources – fishing spots, waterholes, or hunting grounds encroached upon by livestock. Raper’s depictions capture the Eora’s defensive posture, asserting sovereignty.

Cultural exchanges are noted, with some Eora adopting European clothing or learning phrases, but the book highlights the asymmetry: diseases decimated populations, alcohol disrupted social norms, and land theft eroded traditional life. Yet, artworks show resilience, with Eora adapting while maintaining core practices.

Frost’s chapter frames these interactions within settlement dynamics, where initial alliances gave way to resistance. The drawings preserve moments of humanity amid upheaval, reminding us of shared histories.

Conclusion

“The Art of the First Fleet” immortalises Aboriginal society at the threshold of change. On Australia Day 2026, these images compel us to honour the Eora’s legacy, embracing truth-telling for a reconciled future. Recognising their sophistication fosters an inclusive narrative, healing historical wounds.