For almost four decades I have pursued knowledge for its own sake. That pursuit was set in motion by a solid classical education: years of grammar drills, syntax exercises, philological seminars, and immersion in the literature of ancient Greece and Rome. I learned not simply to translate but to read at sight, to think in the idioms of Greek and Latin, and to weigh what the authors themselves recorded against the fragmentary and sometimes tendentious reconstructions that modern politics sometimes produces. Of all the authors I have read again and again in the original – Herodotus, Thucydides, Xenophon, Aristotle, Cicero – none has shaped my historical sensibility more deeply than Herodotus of Halicarnassus. His Histories are not a dry catalogue of events but an embodied practice of inquiry: geography linked to ethnography, memory paired with on-the-spot observation, moral reflection braided into travel report. It is from that practice – my decades-long, first-hand engagement with the classical corpus – that I address the antiquity and endurance of the name “Palestine.”

The question is not an arcane matter of philology only. It bears directly on how we understand the longue durée of the Levant and the ways in which names, peoples, and polities overlay one another over centuries. Some contemporary claims insist that the toponym “Palestine” was an invention of Roman imperial punitive policy in the second century CE and therefore carries a retroactive illegitimacy when applied to earlier times. That claim is historically untenable. The name Palaistinē appears in Greek literature centuries before Rome’s reorganisation of the eastern provinces. Herodotus uses it repeatedly. So do Aristotle, Hellenistic geographers, Roman poets and encyclopaedists, Jewish authors writing in Greek, and later classical compilers. The name was not coined by Hadrian; it was a living toponym embedded in the linguistic and cartographic imagination of the Greeks and Romans for many centuries.

In what follows I examine the evidence – textual, etymological, and archaeological – with a philologist’s attention to language and a historian’s eye for context. My aim is not polemic but fidelity to the record. A clear accounting of what the classical sources say (and do not say) should anchor any honest discussion of the term’s antiquity and use.

Herodotus and the Fifth-Century Greek World

Herodotus wrote in the mid-fifth century BCE, a time when Athens was still the cultural and political centre of the Greek world and when the Persian imperial machine reached across the eastern Mediterranean. Born in Halicarnassus, Herodotus travelled widely along coastal routes from Ionia to Egypt and the Black Sea. His Histories are shaped by those voyages: sea-ways, harbours, ethnographic sketches, and the often competing traditions he encountered on different shores. It is not surprising, then, that his references to the southern Levant are framed by maritime and coastal concerns. His horizons were those of a man who traced the Mediterranean’s littorals; he had less direct access to interior Judaean hill country.

When Herodotus speaks of Παλαιστίνη (Palaistinē) he does so as a familiar geographic marker. He never introduces it as a novel label in need of explanation; it appears in contexts of tribute, movement, and ethnography – matters that presuppose a shared toponymic vocabulary among his readers. That matter-of-fact deployment is historically significant. It shows that, for Greeks of the classical era, the name denoted a recognisable coastal district of the Levant: the corridor that linked Phoenicia in the north with Egypt in the south and that included the chain of port cities and plains long shaped by maritime exchange and cultural contact.

The Seven Herodotean References

In the Histories the term appears at least seven times across several books. Each instance contributes a facet to Herodotus’s working geography of the Levant.

- In Book 1 Herodotus places Scythian incursions and Egyptian responses “in the part of Syria called Palestine,” situating Ascalon on the Palestinian seaboard. The reference is geographical and descriptive, not polemical.

- In Book 2 he groups “the Phoenicians and the Syrians of Palestine” as recipients of an Egyptian custom, again indicating cultural continuity across the coastal zone and a shared pattern of influence derived from Egypt.

- In Book 2 he also records his personal observation of monumental reliefs felt to be in the Palestine part of Syria – a remark that signals he believed himself to have visited or observed the region directly.

- In Book 3 he charts the coastal road that reaches as far as Gaza, “which belongs to the Syrians of Palestine,” showing that Herodotus assigned political or ethnic labels to the coastal strip distinct from the Phoenician polities farther north.

- Book 3’s contribution to the Persian administrative geography lists “the part of Syria called Palestine” alongside Phoenicia and Cyprus in a satrapal unit, which implies that regional nomenclature was intelligible and usable in discussions of the imperial structure.

- In Book 4 he frames a long seaboard as running “by the shore of our Sea along Palestine, Syria, and Egypt,” treating Palestine as one geographic segment among several contiguous coastal regions.

- Finally, in Book 7 he speaks of the “Syrians who dwell in Palestine” providing ships for Xerxes’ fleet and explicitly identifies the region “extending from hence to Egypt” by the name Palestine. This statement is the most expansive and explicatory of the set.

Taken together, these passages show repeated, consistent use: Palestine as a coastal region extending along the Levantine littoral, known to Greek sailors, merchants, and historians. Herodotus does not use the term as a political epithet; he uses it as a geographical label.

Etymology and Semitic Antecedents

The Greek Palaistinē is a Hellenised form of a Semitic root that long pre-dates Greek usage. Egyptian inscriptions of the late Bronze Age and early Iron Age speak of the Peleset – one of the groups associated in Egyptian records with the so-called “Sea Peoples.” In the Hebrew Bible the term appears in the plural Pelishtim and is used repeatedly to denote the Philistines, the peoples who settled the southern coastal strip and established the pentapolis of city-states – Gaza, Ashkelon, Ashdod, Ekron, and Gath – during the early Iron Age. Assyrian records of the first millennium BCE render the name in forms such as Palashtu or Pilistu. These attestations show that a toponym or ethnonym rooted in the Philistine presence existed in Semitic languages centuries before any Greek authors took it up.

Etymology is always a fraught discipline, and it is important not to conflate ethnonymic origins with political claims. The archaeological evidence shows that the Philistines themselves were a composite people with Aegean, Anatolian, and local Canaanite elements. Over time the group’s identity shifted, and the name of their territory could function as both an ethnic marker and – as often happens with toponyms – a territory label that gradually became dissociated from the original ethnic group. That process is hardly unusual in world history: just as “Holland” may stand metonymically for the modern Netherlands, so “Philistia/Palestine” could come to denote a coastal region irrespective of the particular peoples who inhabited it at any given moment.

The Classical Reception: From Aristotle to Ptolemy

Herodotus is not an isolated instance. The name persists across the classical centuries in both Greek and Latin literature, and it appears in contexts as diverse as geography, natural philosophy, poetry, and Jewish historiography. The persistence and neutrality of the term in so many genres are key to understanding its character.

Aristotle, writing within a century of Herodotus, cites “a lake in Palestine” in his Meteorology when discussing the peculiar buoyancy of the Dead Sea and its effects on organic matter. His tone is scientific and empirical; he does not marshal the term for ideological ends. The Hellenistic geographers and historians – many of whom drew on earlier, now-lost accounts – continue to use the name. Diodorus Siculus preserves traditions that place features “over against Petra, and Palestine,” suggesting an expansion of the label inland in some descriptions. In the Roman period, Strabo devotes a substantial section of his Geography to the Syrian provinces and uses Palestine as a regional term alongside Judaea, distinguishing coastal plain and inland hill country without apparent polemical intent.

Latin authors adopt the term seamlessly into Roman geographical idiom. Pomponius Mela, one of the earliest Roman geographers, lists Gaza and Ascalon among the towns of Palestine. Poets such as Tibullus and Ovid employ the name in passing, often to evoke exotic geography or liturgical detail; Ovid’s references to Sabbaths and to regional ethnography in his poetic works show that the name served as a cultural marker intelligible to a Roman readership.

Pliny the Elder’s encyclopaedic survey treats “Palestine” as an established regional unit, noting that parts of the land adjacent to Arabia had been called Palestine. Ptolemy’s Geography situates cities by coordinates and labels the region plainly. The Jewish authors of Greek prose – Philo of Alexandria and Flavius Josephus – use the term without embarrassment. Philo refers to Palestine alongside Phoenicia and Coele-Syria in describing Moses’ wanderings and in other contexts, while Josephus, who wrote in a Roman imperial milieu and sought to explain Jewish history to Greco-Roman readers, employs Palestine alongside Judaea to describe the broader Levant. The implication is clear: for a broad range of classical authors, across languages and genres, Palestine was a stable geographic denotation.

The Roman Rebranding after 135 CE

It is sometimes asserted that the name “Palestine” was invented or introduced by the Roman administration as an explicitly punitive measure following the Bar Kokhba revolt (132–136 CE). The edict that re-founded Jerusalem as Aelia Capitolina and barred Jews from its precincts was indeed an act of imperial policy designed to mark imperial supremacy and to reshape the city’s civic identity. Hadrian’s decision to adopt the episcopal cult and urban refoundation fit within Roman practices of commemoration and re-foundation.

But there is a critical distinction to be made between renaming a province for administrative and ideological reasons and inventing a completely new toponym. The latter does not match the historical record. By the time of Hadrian, Palaestina had been a recognisable label for centuries. Roman administrators, faced with a politically charged provincial name like Judaea, could choose to subsume and rename territories with existing, widely comprehensible terms; selecting Palaestina for the reconstituted province was therefore an administrative strategy that drew on an existing cartographic language. The renaming had punitive aspects, certainly, insofar as it aimed to diminish the particularity of Judaean identity in the imperial registry; but it did not create the term out of nothing. It was a reapplication and enlargement of an established label.

Archaeology and the Philistines

Archaeological work has deepened our understanding of the coastal cultures of the southern Levant and their interactions with the wider Mediterranean. Excavations at Philistine sites reveal pottery traditions with Aegean affinities, architectural forms that show external influences, and continuity with local Canaanite practices. This hybrid material culture supports the idea that the “Philistines” were not a monolithic invader but a group whose identity crystallised through complex interactions. Over time, as the material and political landscape transformed – through Assyrian, Babylonian, Persian, Hellenistic, and Roman rule – the label attached to the coastal zone also transformed in resonance.

Importantly, archaeological evidence also corroborates continuous Jewish presence in the highlands and in Jewish communities along the coastal plain and in the interior. Material culture and epigraphic finds show a persistence of Jewish ritual life, inscriptions, and settlement patterns from the Iron Age through the late antique period. These strands are not mutually exclusive. The Levant is a palimpsest: successive layers of settlement and identity overlie one another and sometimes coexist in the same horizon.

Language, Identity, and the Non-Zero-Sum Past

One of the persistent errors in contemporary discourse is to treat history as zero-sum: for one name to be true, another must be false; for one people’s claim to hold, another must be erased. The classical sources resist that logic. The ancients were not naively pluralistic; they often wrote from partisan positions and with obvious biases. But they also recorded a world in which multiple identities coexisted and sometimes overlapped. The co-presence of Judaea as a polity and Palaistinē as a geographic term is precisely such a historical reality. Jewish kings and councils ruled inland territories, while the coastal plain retained its own networks of cities and cultural connections; both existed within the larger matrix of Near Eastern polities and imperial administrations.

To insist, retrospectively, that one ancient name comprehensively eliminates another is to misunderstand how ancient authors and peoples used language. Names carried different valences – ethnic, regional, administrative – and they shifted in force depending on the speaker’s perspective and the period. Herodotus’s sailors, Aristotle’s natural philosophers, Roman poets, and Jewish historians each employed the toponym in contexts that suited their purposes. That multiplicity of usages does not dissolve historic truth; rather, it is a hallmark of a region shaped by layered histories.

The Duty of Intellectual Honesty

As a scholar formed in the classical tradition, I believe intellectual honesty requires three commitments: fidelity to the texts as we have them; an awareness of the limits of those texts; and a reluctance to let modern political imperatives wholly subordinate historical evidence. The first two commitments are methodological; the third is moral. The historian’s craft is to weigh sources against one another, to parse genre and bias, and to situate statements in their immediate contexts. This is what Herodotus attempted in his own way: an inquiry that combined reported testimony with personal observation, with an awareness that his informants might be partial.

When modern actors assert that “Palestine” is a modern invention, they are not merely making a historical claim but implicitly seeking to flatten the complex temporal contours of identity in the Levant. Conversely, when proponents of Palestinian national legitimacy assert a direct, unbroken lineage from a classical geographical name to a modern national identity, they risk anachronism – foregoing the necessary distinction between a toponym and the political subjectivities that it may be made to serve. Both moves – denial and absolutisation – are forms of instrumentalising the past.

History, however, is not a political weapon to be wielded in toto. It is a body of evidence and interpretation that constrains argument. The classical record – Herodotus, Aristotle, Strabo, Pliny, Ptolemy, Philo, Josephus – shows Palaistinē to be a recognised geographic term centuries before Hadrian. Archaeology corroborates the longue durée of both Philistine-related cultures on the coast and Jewish presence in the highlands. To acknowledge these facts is not to subscribe to any modern political programme; it is simply to accept the evidence where it leads.

Conclusion: Names as Windows to Complexity

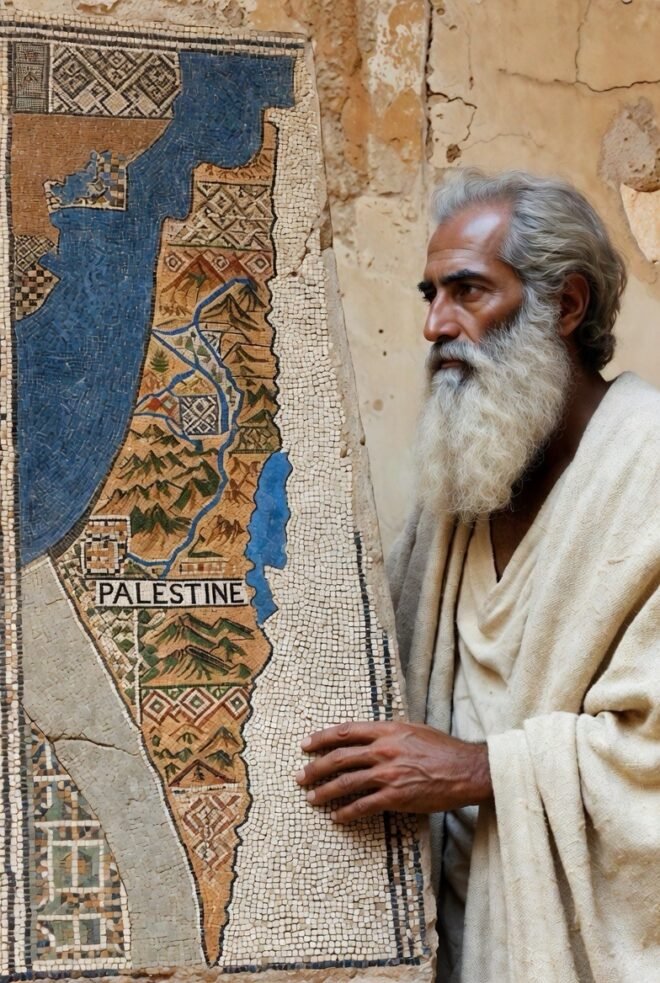

The endurance of the name “Palestine” in the classical tradition offers an instructive case study for how names function over time. They are, at once, markers of space, carriers of memory, and instruments of administrative power. They may be appropriated, reactivated, or suppressed by rulers, yet their longevity often reveals deeper continuities in trade routes, settlement patterns, and cultural exchange.

Herodotus and his successors did not invent this permanence. They recorded a linguistic and geographic reality that had been articulated in Egyptian and Semitic archives centuries earlier. The Roman decision to rename the province in the wake of the Bar Kokhba revolt was politically significant but not creative of a new place-name in a vacuum. It repurposed an existing term within an imperial framework. Both truths can be held: the Roman renaming was an act of imperial redefinition; the toponym itself was ancient.

The historian’s vocation is to embrace complexity, to resist simplifications that serve contemporary agendas, and to restore to the past the integrity that modern polemics would strip away. In that spirit, let us allow the primary sources to speak plainly: Herodotus’s Palaistinē is not an invention of Hadrian; it is the echo of older Semitic names, transmitted into Greek, and adopted by successive generations of writers who found the term serviceable for describing a particular stretch of the eastern Mediterranean littoral. That layered history – Philistine city-states, Phoenician harbours, Judaean highlands, Persian satrapies, Hellenistic polities, and Roman provinces – constitutes the rich mélange of the land we may call, in different idioms and at different times, Palestine, Judaea, Canaan, or the Holy Land.

The task for modern readers is not to use the past as a weapon but to learn from it. The classical witnesses, taken in good faith, show a region of overlapping names and persistent presences. They teach a modest lesson: to understand the past, one must read it carefully; to use it well, one must be honest about what the texts actually say. Herodotus’s inquiries invite no less of us.