To truly grasp the depth and richness of Aboriginal culture prior to the British-led European invasion, one must delve into its ceremonies and the intricate symbolism of the Dreamtime. These elements are not mere performances or abstract myths; they are living expressions of a worldview that intricately weaves together the physical and spiritual, the temporal and eternal. Aboriginal ceremonies, alive with rhythm, song and dance, form the heartbeat of a culture where every chant, movement and symbol is a thread in the tapestry of the Dreamtime – the foundational narrative that binds humanity, nature and the cosmos in an unending cycle of creation and renewal. Dreamtime symbolism, manifested through art, ritual and storytelling, serves as a dynamic language, encoding the spiritual truths and ancestral stories that define Aboriginal identity. Together, ceremony and symbolism reveal a culture of profound interconnectedness, where the land, the ancestors and the living are united in a sacred continuum.

The Ceremonial Symphony: Rhythm, Song and Movement

Aboriginal ceremonies are multisensory experiences, orchestrated by the songman whose voice and rhythmic tapping of sticks or boomerangs set the tempo. The songman acts as both conductor and storyteller, weaving ancestral narratives that resonate with the land and its spirits. The steady pulse of his tapping is the heartbeat of the ceremony, grounding participants in a shared rhythm that echoes the cycles of nature. Accompanying this is the didgeridoo, its deep, resonant tones providing a cosmic foundation that reverberates through the gathering. The didgeridoo’s sound is not merely musical, but a reflection of the primal forces of creation, adding depth to the layered superstructure of song, stick-taps and vocal expressions that punctuate the ritual.

The dancers, adorned with intricate body paint and ceremonial regalia, embody the stories being told. Their movements are precise, each step and gesture synchronised with the songman’s rhythm, translating the chant’s themes into physical form. The drama unfolds not only in the dancers’ movements, but in the collective energy of the ceremony, where bystanders contribute to the rhythmic chorus through clapping and swaying.

This is not a performance for spectators; it is a communal act of creation, where every participant – dancer, singer, or bystander – is a vital thread in the ceremonial fabric. The painted patterns adorning bodies, boomerangs and didgeridoos are sacred symbols, each tied to a specific totem or ceremonial group. These designs form a visual language, encoding stories of ancestry, land and spiritual identity. In secret rites, additional objects – painted or engraved wood, stone, or composite materials – serve as conduits to the Dreamtime, directing thoughts toward the eternal beings and forces that shape existence.

The Dreamtime: A Mystic Framework

Understanding Aboriginal ceremony requires an understanding of the Dreamtime, known as Tjukurrpa in some Aboriginal languages. The Dreamtime is not a distant past but an ever-present reality, a mystic realm where ancestral beings created the world, shaping its landscapes, laws and lifeforms. These beings, often embodied as animals, spirits, or natural forces, continue to inhabit the land, their presence felt in the rustle of leaves, the flow of rivers and the pulse of ceremony. The Dreamtime serves as both origin and destiny, ensuring the eternal renewal of nature and humanity through ritual re-enactment.

Ceremonies are the physical manifestation of the Dreamtime, bridging the material and spiritual planes. Through dance, song and symbolic art, participants reenact the creative acts of ancestral beings, re-affirming their connection to the land and its sacred stories. The ritual dance is not mere mimicry, but a sacred art form, embodying the unity of dance, singing, poetry and visual arts. This holistic expression of Aboriginal culture ensures that no element – be it a painted pattern, a carved object, or a chanted verse – exists in isolation. Together, these elements form a living narrative, attesting to the enduring power of the Dreamtime.

The Dreamtime is the foundation of Aboriginal cosmology, a framework that perceives the world as interconnected and dynamic. Every rock formation, river, or tree is a marker of the Dreamtime, embodying the actions of the ancestors who shaped it. Ceremonies held at these sacred sites are not just performances but re-enactments of the Dreamtime, where the symbols painted on bodies, the songs sung and the dances performed align with the spiritual essence of the landscape. This alignment ensures the renewal of the land and its people, maintaining the balance established by the ancestors.

Dreamtime Symbolism: A Language of the Sacred

Dreamtime symbolism is the intricate language through which the spiritual and cultural truths of the Dreamtime are expressed. Manifested in art, ceremony, storytelling and sacred objects, these symbols are deeply meaningful, encoding the stories, laws and spiritual connections that define Aboriginal identity. Unlike Western symbols, which often have fixed meanings, Dreamtime symbols are fluid and layered, their significance shaped by the specific narrative, totemic affiliation, or ceremonial purpose they serve. A single symbol – a circle, a wavy line, or a series of dots – can represent different concepts depending on the story being told or the cultural group interpreting it.

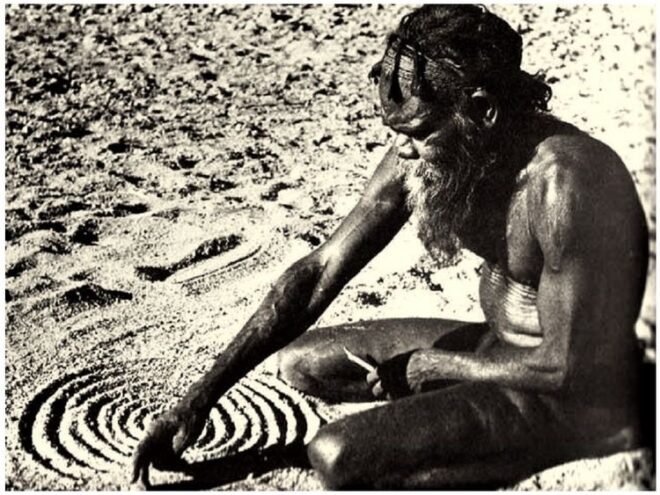

At its core, Dreamtime symbolism communicates the sacred, serving as a bridge between the tangible world of human experience and the intangible realm of the Dreamtime, where ancestral beings continue to shape existence. These symbols are not mere representations, but are imbued with the power of the ancestors, making them active participants in the rituals and stories they adorn. Whether painted on a body, carved into a sacred object, or traced in the sand, each symbol is a sacrament, a physical manifestation of the spiritual forces that underpin the Aboriginal worldview.

Common Dreamtime Symbols and Their Meanings

While the interpretation of Dreamtime symbols varies across Aboriginal cultures and regions, certain motifs are widely recognised and carry broadly understood meanings. These symbols are often depicted in rock art, body painting, ceremonial objects and contemporary Aboriginal art, serving as a visual lexicon for the stories of the Dreamtime. Some of the most common symbols include:

• Circles: Often representing a waterhole, campsite, or meeting place, circles symbolise a point of connection or sustenance. Concentric circles may indicate a sacred site or the journey of an ancestral being, with each ring representing a stage in the narrative.

• Wavy Lines: Typically symbolising water, such as rivers or rain, wavy lines may also represent the tracks of ancestral beings, evoking the flow of spiritual energy or the life-giving power of water.

• Dots: Iconic in Aboriginal art, dot patterns can represent stars, seeds, or the tracks of animals or ancestors. They may symbolise spiritual energy or the multitude of beings within the Dreamtime.

• U-Shapes: Often representing a person sitting, U-shaped marks may depict gatherings for rituals, emphasising the communal nature of Aboriginal life.

• Tracks and Footprints: Resembling footprints or animal tracks, these patterns represent the journeys of ancestral beings, forming a map of the Dreamtime that is both physical and spiritual.

• Animal and Plant Motifs: Specific animals or plants often appear as totemic symbols, representing the ancestral beings associated with a particular clan or region.

Symbolism in Ceremonial Contexts

In Aboriginal ceremonies, Dreamtime symbolism comes to life through a dynamic interplay of visual, auditory and kinaesthetic elements. Body painting, sacred objects and ritual performances are vehicles for these symbols, each activating the spiritual power of the Dreamtime. The patterns painted on participants’ bodies are specific to their totemic affiliations and the narrative of the ceremony, creating a deep connection to their ancestral story.

Sacred objects, such as engraved stones or carved wooden tjuringa, are central to many ceremonies, particularly secret rites. These objects often bear intricate patterns that encode specific Dreamtime stories or laws, guiding the initiated toward a deeper understanding of the spiritual world. The symbols on these objects are believed to contain the essence of the ancestors, making them powerful tools for communion with the Dreamtime.

In ritual dance, symbolism extends to movement and gesture. The stamping of feet, swaying of bodies and expressive motions reflect the actions of ancestral beings. A dance may mimic the hopping of a kangaroo or the slithering of a serpent, embodying the ancestor’s creative journey across the land. These movements are accompanied by the rhythmic tapping of boomerangs or sticks and the drone of the didgeridoo, whose sounds evoke the primal forces of creation.

The Sacred Art of Aboriginal Australia

Aboriginal ceremony is a masterwork of sacred art, encompassing performance as well as visual and material arts. The intricate body paintings, engravings, carvings and sculptures that adorn participants and ceremonial objects are profound expressions of cultural and spiritual identity. These artworks are imbued with the stories of the Dreamtime, serving as visual narratives that connect the present to the eternal. The act of creating these works – whether painting a boomerang, carving a sacred object, or moulding a composite form – is itself a ritual, aligning the artist with the ancestral forces they depict.

Dance serves as a choreography of meaning, where every movement is deliberate and symbolic. The stamping of feet, swaying of bodies and expressive gestures reflect the stories being sung. This dance is a dialogue between the human and the divine, a physical enactment of the Dreamtime’s creative acts. The rhythm of the songman’s sticks, the drone of the didgeridoo and the collective clapping of the chorus create a multi-sensory experience that engages sight, sound and movement.

Poetry is woven into the fabric of ceremony through the songman’s chants, carrying the weight of ancestral wisdom. Layered with metaphor, their meanings are often accessible only to those initiated into the deeper mysteries of the culture. The accented exclamations, hisses, “breathings,” and shouts that punctuate the chants add emotional and spiritual intensity, drawing participants and listeners into a shared state of reverence and awe.

The Communal and the Sacred

Aboriginal ceremonies are profoundly communal, uniting participants in a shared act of cultural and spiritual renewal. Unlike Western performances, which distinguish between performer and audience, Aboriginal ceremonies blur these boundaries. Every individual present contributes to the ritual, whether through clapping, swaying, or silent reverence. This collective participation reflects the Aboriginal understanding of interconnectedness – not only among people but between humanity, the land and the spiritual world. The ceremony serves as a microcosm of this interconnectedness, a space where the boundaries between self and other, human and ancestor, dissolve in the shared rhythm of the Dreamtime.

For women, who may be excluded from men’s secret ceremonies, participation takes on different yet equally meaningful forms. Their subtle movements at the edge of the dance-ground, often accompanied by string games, embody the complementary roles of men and women in maintaining cultural continuity. These string games, sometimes performed without string, represent the interconnected webs of kinship, land and story that define Aboriginal life.

In secret ceremonies, the use of sacred objects and restricted symbols underscores the layered nature of Aboriginal spirituality. These rites, accessible only to initiated individuals, delve into the deepest mysteries of the Dreamtime, using objects as focal points for meditation and communion with ancestral beings. The secrecy is not about exclusion but about protection, ensuring that the most sacred knowledge is shared only with those prepared to bear its weight. Initiation ceremonies, marking the transition to adulthood, involve the revelation of sacred symbols and their meanings, requiring initiates to internalise the symbols through participation and connection to the land.

Symbolism and the Land

The land itself serves as a canvas for Dreamtime symbolism, with its features acting as living symbols of the ancestral past. Every rock formation, river, or tree is a marker of the Dreamtime, embodying the actions of the ancestors who shaped it. A rock outcrop may be seen as the petrified body of an ancestral being, its cracks and contours narrating their journey. The symbols used in art and ceremony are often maps of this sacred geography, guiding participants to the sites where the Dreamtime unfolds. This connection to the land underscores the holistic nature of Dreamtime symbolism, integrating the visual, auditory and spatial dimensions of Aboriginal culture.

Ceremonies held at sacred sites align the symbols painted on bodies, the songs sung and the dances performed with the spiritual essence of the landscape. This alignment ensures the renewal of the land and its people, maintaining the balance established by the ancestors. The land is not a passive backdrop but an active participant in the ceremony, resonating with the rhythms and symbols of the Dreamtime.

The Eternal Cycle of Renewal

At its core, Aboriginal ceremony is an act of renewal, a ritual re-affirmation of the eternal life of nature and humanity. By re-enacting the creative acts of the Dreamtime, participants ensure the continuity of the world as they know it. The land, the ancestors and the living are bound together in a cycle of mutual dependence, where ceremony is both a gift to the spiritual world and a means of receiving its blessings. This reciprocity is the essence of Aboriginal culture, a worldview that sees humanity not as separate from nature but as an integral part of its sacred order.

The symbols, songs and dances of ceremony are not static relics but living practices that adapt to the needs of each generation. While the core stories and rituals remain unchanged, their expression evolves, reflecting the resilience and creativity of Aboriginal culture. Even in the face of colonial disruption, these ceremonies have endured, a testament to the strength of a culture rooted in the eternal truths of the Dreamtime.

Contemporary Expressions of Dreamtime Symbolism

Dreamtime symbolism remains a vibrant part of contemporary Aboriginal culture, adapting to new contexts while retaining its sacred essence. Artists from movements like Papunya Tula have brought Dreamtime symbols to global audiences, using acrylic paints and canvas to depict ancestral stories. These works often retain traditional iconography – circles, lines and dots – but balance the need to share cultural knowledge with the imperative to protect sacred elements. In modern contexts, Dreamtime symbolism serves as a means of cultural resilience and identity, allowing Aboriginal communities to assert their connection to the land and ancestors despite historical disruption.

Even in urban settings, where access to traditional lands may be limited, the symbols of the Dreamtime provide a spiritual anchor, linking individuals to their cultural heritage. The act of creating art, performing ceremonies, or sharing stories is a way of maintaining continuity, ensuring that the Dreamtime remains a living presence in Aboriginal life.

Conclusion

To fully appreciate the breadth and meaning of Aboriginal culture prior to European invasion, one must experience its ceremonies and engage with the profound symbolism of the Dreamtime. To hear the songman’s chant, the didgeridoos’s drone and the dancers’ stamping feet is to encounter a culture alive with meaning, where every sound, movement and symbol is a thread in the eternal tapestry of the Dreamtime. These ceremonies are sacred acts of creation, renewal and connection, embodying the unity of humanity, nature and the spiritual world. Dreamtime symbolism, with its fluid and layered meanings, is the language of this sacred reality, encoding the stories and laws that define Aboriginal identity. Together, ceremony and symbolism reveal a culture of unparalleled depth, rooted in the land and its sacred past, yet resilient and adaptive in the face of change. In their rhythms, symbols and stories, we glimpse the enduring promise of the Dreamtime, where the ancestors continue to shape the world and its people in an eternal cycle of renewal.