Australia is often celebrated as a land of opportunity, a nation where hard work and determination are believed to guarantee success for anyone willing to strive. This narrative of meritocracy, however, conceals a stark reality: the nation’s social, economic and educational systems disproportionately favour those born into privilege – typically white, wealthy individuals or those from affluent areas – while marginalising Indigenous Australians, migrants and low-income communities. Far from rewarding merit alone, Australia’s structures, including its deeply unequal education funding model, economic policies and historical legacies, entrench systemic inequities. By examining the role of privilege, the disparities in education funding, the enduring impact of colonialism and racism and the influence of powerful economic interests, this essay argues that the meritocracy myth denigrates hardworking Australians and sustains an unjust status quo. True equality demands bold, systemic reforms to dismantle these barriers and create a society where opportunity is genuinely accessible to all.

The Foundations of Privilege in Australian Society

Privilege, the unearned advantages tied to race, class or geography, forms the bedrock of Australia’s social hierarchy. Many of the nation’s most affluent and influential individuals owe their success not to personal effort, but to the circumstances of their birth: being white, growing up in wealthy families, living in affluent neighbourhoods or attending well-resourced, predominantly white schools. These advantages accumulate over time, creating a self-perpetuating cycle where privilege begets more privilege, undermining the notion of a level playing field.

Wealth is a central pillar of privilege and in contemporary Australia, it often stems from passive sources rather than traditional notions of hard work. The wealthiest individuals frequently derive income from investments, such as stocks or real estate, rather than from labour-intensive endeavours. Tax policies, such as deductions for investment properties or favourable treatment of capital gains, enable the affluent to amass fortunes while ordinary workers rely on wages that barely keep pace with rising costs. For many low-income earners, expenses like rent, food and utilities consume most of their income, leaving little room for savings or investment. This disparity challenges the claim, often echoed by commentators, that success results from diligence, industriousness or self-reliance. Instead, wealth in Australia is increasingly about leveraging existing resources, not earning rewards through effort alone.

Privilege extends beyond finances to include access to social networks, quality housing and cultural knowledge, all of which reinforce economic divides. Affluent families can afford to live in areas with better infrastructure, safer communities and proximity to influential networks, securing opportunities that others cannot access. Children from wealthy households often benefit from family connections that lead to internships, mentorships or entry into high-paying professions. In contrast, those from less advantaged backgrounds must navigate a system with fewer resources and connections, making upward mobility far more difficult. This reality exposes the meritocratic ideal as a myth, revealing a society where outcomes are often shaped by birth, not by individual merit.

Education Funding: A Microcosm of Systemic Inequality

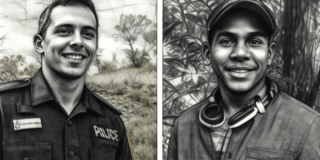

The education system, frequently celebrated as a pathway to social mobility, is one of the clearest examples of how privilege is perpetuated in Australia. Unequal funding ensures that only those already advantaged – typically white, wealthy or from affluent areas – fully benefit from educational opportunities, while disadvantaged groups, including Indigenous Australians, migrants and low-income students, are left struggling in under-resourced schools. This disparity undermines the meritocratic narrative and entrenches social and economic divides.

Education in Australia is funded through a combination of federal and state government contributions, with private schools also relying on parental fees. The goal of funding is to provide every student with a quality education, but in practice, the system favours wealthier communities. Public schools, which educate the majority of students, often receive less funding than needed to maintain adequate facilities, hire experienced teachers or offer diverse programs. Private schools, particularly elite institutions, benefit from higher government grants relative to their needs and can charge substantial fees, enabling them to provide state-of-the-art facilities, smaller class sizes and extracurricular activities that enhance student outcomes.

The consequences of this funding gap are evident in the quality of education provided. Schools in affluent, predominantly white areas offer advanced courses, such as specialised science or arts programs and employ highly qualified teachers who can provide individualised attention. These schools prepare students for prestigious universities and competitive careers, giving them a significant advantage. In contrast, public schools in disadvantaged areas – often serving Indigenous, migrant or low-income students – struggle with outdated buildings, limited technology and larger classes. Teachers in these schools, while dedicated, may lack the resources to address diverse student needs, such as language support for migrants or tailored programs for students with learning difficulties.

For Indigenous students, the funding disparity is particularly acute. Schools in remote communities, where many Indigenous Australians live, often lack basic infrastructure, such as libraries or science labs and face challenges attracting qualified staff due to geographic isolation. This results in lower graduation rates and limited access to higher education or skilled employment. Migrant and refugee students, particularly those from non-English-speaking backgrounds, also face barriers in underfunded urban public schools, where programs to support language acquisition or cultural integration are often inadequate. These students may disengage or drop out, limiting their future opportunities.

The education funding model reflects a broader societal bias toward privilege. Wealthy families can afford private school fees or to live in areas with well-funded public schools, ensuring their children receive a superior education. This creates a cycle where advantaged students secure better jobs, accumulate wealth and pass on opportunities to their own children. Meanwhile, students from disadvantaged backgrounds are funnelled into under-resourced schools, restricting their prospects and perpetuating poverty. The notion that education levels the playing field is thus a fallacy; instead, it reinforces existing inequalities, ensuring that privilege, not merit, determines educational and economic outcomes.

The Myth of Meritocracy and Its Consequences

The belief in meritocracy – that anyone can succeed through hard work alone – is deeply ingrained in Australia’s national identity. This narrative is appealing because it promises fairness and rewards for effort, but it ignores the structural barriers, such as unequal education funding, that prevent equal opportunity. By framing success as a matter of individual achievement, the meritocracy myth shifts blame onto those who struggle, suggesting their failure stems from laziness or lack of ambition rather than systemic inequities. This perspective denigrates the efforts of countless Australians who work tirelessly under challenging conditions.

Low-wage workers, many of whom are migrants, Indigenous Australians or from disadvantaged backgrounds, embody the diligence and industriousness celebrated by the meritocracy myth, yet they are denied its promised rewards. These individuals often labour in physically demanding or precarious jobs – cleaning, construction, retail or caregiving – for wages that barely cover living expenses. Their children, attending underfunded schools, face limited prospects for upward mobility, trapping families in a cycle of disadvantage. In contrast, the children of affluent families benefit from well-resourced education and social networks, securing high-paying careers with relative ease. The meritocracy myth obscures this reality, portraying success as a personal triumph rather than a product of systemic advantage.

Inherited advantage further exposes the myth. Wealthy families pass on not only financial resources, but also access to elite education, professional networks and cultural knowledge. A child from an affluent family might receive tutoring, attend a prestigious school and secure a university place with ease, while a child from a low-income family must overcome underfunded schools, financial stress and limited guidance. The outcomes – university degrees and high-paying jobs for one, limited opportunities for the other – are less about merit and more about the resources available from birth. By ignoring these disparities, the meritocracy myth absolves the privileged of responsibility for perpetuating an unequal system and denigrates those who work hard, but cannot break through systemic barriers.

The Legacy of Colonialism and Racism

Australia’s inequalities are deeply rooted in its colonial history and persistent racism, which continue to shape access to education, wealth and opportunity. The nation was built on the dispossession of Indigenous lands, with policies that favoured white settlers and marginalised Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples. This historical injustice created a foundation of unequal access to resources, including education, that persists today. Indigenous Australians often attend underfunded schools, particularly in remote areas, where limited resources and cultural disconnects hinder academic success. The lack of culturally relevant curricula or support for Indigenous languages can lead to disengagement, lower graduation rates and restricted economic opportunities.

Racism also affects non-Indigenous minorities, such as migrants and refugees from non-European backgrounds. These groups frequently face discrimination in education, employment and housing, which limits their ability to compete on equal terms. In underfunded public schools, migrant students may lack access to language support or programs that address their unique needs, leading to higher dropout rates and fewer pathways to higher education. In the workforce, discriminatory hiring practices can confine migrants to low-paying jobs, regardless of their qualifications or efforts. These barriers reinforce economic inequality, as marginalised groups are systematically excluded from the opportunities available to white Australians.

The market, often touted as a neutral mechanism for distributing resources, amplifies these inequities. White Australians, with greater historical access to education, wealth and political influence, are better positioned to accumulate resources and shape systems in their favour. For example, affluent families can secure places in well-funded schools, ensuring their children’s success, while disadvantaged groups are relegated to under-resourced institutions. If Australia were truly meritocratic, everyone – Indigenous Australians, migrants and others – would start on equal footing. Instead, the legacy of colonialism and racism ensures that the playing field remains uneven, with privilege determining access to opportunity.

The Role of Economic Interests

Powerful economic interests play a significant role in maintaining Australia’s inequitable systems. Wealthy individuals, corporations and industry groups wield influence to shape policies that prioritise their interests, often at the expense of the broader public. In education, private schools benefit from generous government funding and lobbying efforts that preserve their advantages, while public schools struggle with inadequate resources. This dynamic ensures that affluent families maintain access to superior education, perpetuating their economic dominance.

In the broader economy, policies like tax breaks for property investors or subsidies for large industries favour the wealthy, enabling them to accumulate wealth with minimal effort. For example, deductions for investment properties allow affluent individuals to reduce their tax burden while driving up housing prices, making homeownership unattainable for many. Meanwhile, low-wage workers face rising costs and stagnant incomes, with little access to such financial advantages. The influence of economic elites extends to tax avoidance, where large corporations exploit loopholes to minimise contributions to public coffers, limiting funds for education, healthcare and social services.

These economic arrangements reinforce the status quo, concentrating wealth and opportunity among a small elite. The ability of powerful interests to shape policy undermines democratic fairness, ensuring that the system serves the privileged rather than the public. This reality further exposes the meritocracy myth, as success is often determined by access to influence and resources, not by hard work or talent.

Toward a Fairer and More Equitable Society

Creating a truly equitable Australia requires dismantling the myth of meritocracy and confronting its structural underpinnings. Education reform is a critical starting point. Equitably funding public schools would ensure that all students, regardless of background, have access to quality facilities, qualified teachers and diverse programs. Prioritising resources for disadvantaged areas, particularly remote Indigenous communities and urban migrant-heavy schools, could address gaps in infrastructure, language support and cultural inclusion. Investing in early childhood education would provide a strong foundation for all children, reducing disparities before they enter primary school. Reducing funding disparities between public and private schools would level the playing field, ensuring that education rewards talent, not wealth.

Economic reforms are equally essential. Introducing progressive taxation, such as higher taxes on wealth or investment income, would generate revenue to fund public services like education and healthcare. Closing tax loopholes for corporations and affluent individuals would ensure that everyone contributes fairly to society’s needs. Reforming property investment policies, such as limiting deductions, would improve housing affordability, giving low-income families a chance to build wealth. Raising minimum wages and strengthening labour protections would reward the efforts of low-wage workers, many of whom are migrants or Indigenous Australians and provide pathways to economic stability.

Addressing the legacy of colonialism and racism requires targeted action. Incorporating Indigenous perspectives into school curricula and hiring more Indigenous educators would foster cultural pride and engagement among Aboriginal students. Providing robust language and cultural support for migrant and refugee students would help them thrive academically and socially. Strengthening anti-discrimination laws and promoting diversity in workplaces would ensure fairer access to employment and economic opportunities. Recognising and addressing the intergenerational trauma caused by colonial policies is also essential to fostering reconciliation and equality.

Finally, curbing the influence of powerful economic interests is crucial to creating a more democratic society. Limiting lobbying by private schools and corporations, increasing transparency in political decision-making and empowering community voices would ensure that policy serves the public interest. Supporting grassroots movements and amplifying the perspectives of marginalised groups would shift power toward those most affected by inequality.

Conclusion

The myth of meritocracy in Australia is a seductive, but flawed narrative that obscures the realities of privilege, power and systemic inequality. Unequal education funding ensures that affluent, predominantly white students access superior opportunities, while Indigenous, migrant and low-income students are left behind in under-resourced schools. Combined with the legacy of colonialism, persistent racism and the influence of economic interests, these structures perpetuate a system where success is determined by birth, not merit. Dismantling this system requires bold reforms: equitable education funding, progressive economic policies and justice for marginalised groups. Only then can Australia become a society where opportunity is truly universal and the fruits of prosperity are shared by all, reflecting a commitment to fairness and equality for every citizen.