Introduction

The AUKUS (Australia-United Kingdom-United States) security partnership, announced in September 2021, was heralded as a transformative alliance aimed at bolstering Indo-Pacific security amid rising tensions with China. At its core, AUKUS involves the transfer of nuclear-powered submarine technology to Australia, enabling the country to acquire up to eight conventionally armed, nuclear-propelled submarines (SSNs). This “optimal pathway” includes purchasing Virginia-class submarines from the US in the 2030s, followed by jointly developing the SSN-AUKUS class with the UK. Proponents argue it enhances deterrence, strengthens alliances, and positions Australia as a key player in regional stability. However, a closer examination reveals AUKUS as a profoundly flawed deal for Australia, burdened by exorbitant costs, uncertain delivery, erosion of national sovereignty, strained trade relations with China, viable cheaper alternatives, and the wildcard of Donald Trump’s notorious disregard for international agreements.

As of August 2025, with Trump back in the White House following his 2024 election victory over Kamala Harris, the pact faces intensified scrutiny. Trump’s administration has initiated a review of AUKUS, raising doubts about its future amid his “America First” policies and history of scrapping deals like the Paris Climate Accord and the Iran nuclear agreement. This essay argues that AUKUS represents a strategic misstep for Australia, locking the nation into a dependency that prioritises US interests over its own. Drawing on recent developments, expert analyses, and economic data, it dissects the pact’s pitfalls, substantiating why Australia should reconsider or exit this arrangement before it inflicts irreversible damage.

The pact’s origins trace back to Australia’s cancellation of a $90 billion deal with France for diesel-electric submarines, a move that strained relations with Paris and signalled a pivot toward deeper US-UK integration. While AUKUS encompasses two pillars – submarine acquisition (Pillar I) and advanced technologies like AI and hypersonics (Pillar II) – the submarine component dominates discourse due to its scale and risks. Australia’s commitment involves hosting US and UK submarines from 2027, purchasing used Virginia-class boats, and building new ones domestically by the 2040s. Yet, as costs balloon and geopolitical winds shift, the deal’s viability crumbles.

Critics, including former Prime Ministers Malcolm Turnbull and Paul Keating, label it a “colossal surrender” of sovereignty. In an era of fiscal restraint and global uncertainty, Australia must prioritise pragmatic defence over alliance symbolism. This essay explores each dimension of why AUKUS is detrimental, building a case for re-evaluation. Additionally, it examines the role of former Prime Minister Scott Morrison, who spearheaded the deal, and questions whether personal vested interests influenced his decisions, given his subsequent lucrative post-political career in defence-related sectors.

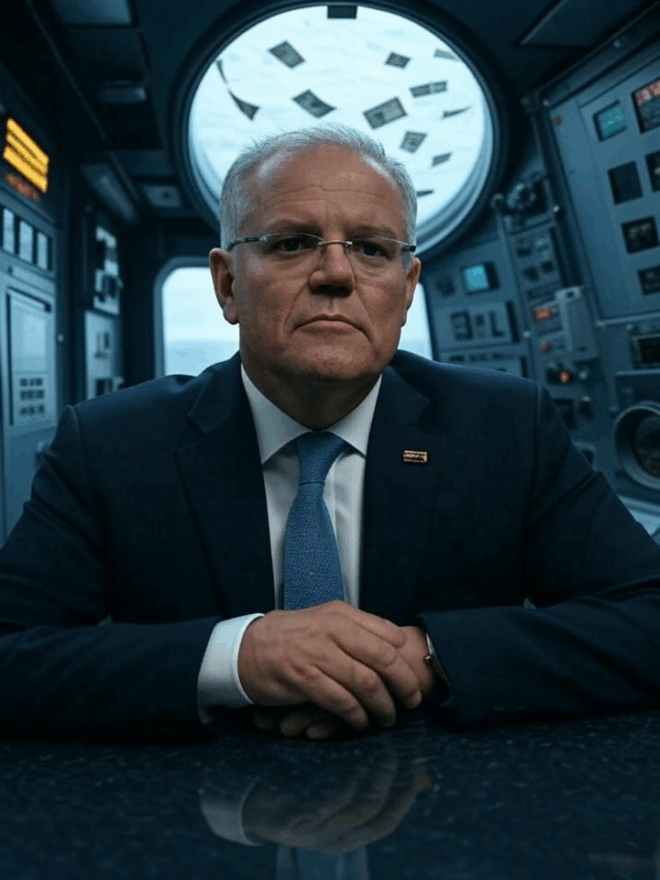

Scott Morrison’s Role and Potential Vested Interests

Scott Morrison, as Prime Minister from 2018 to 2022, was the architect of AUKUS, announcing the pact alongside US President Joe Biden and UK Prime Minister Boris Johnson in a virtual press conference that caught many by surprise. His government framed the deal as essential for countering China’s growing influence in the Indo-Pacific, emphasising the strategic advantages of nuclear-powered submarines over the diesel-electric ones previously contracted with France. Morrison described AUKUS as Australia’s “moon shot,” a bold leap in defence capability that would ensure long-term security. He argued that the shifting strategic environment, marked by China’s military expansion, rendered the French submarines obsolete, necessitating a pivot to nuclear propulsion shared only with trusted allies.

However, Morrison’s enthusiasm for AUKUS raises questions about potential conflicts of interest, particularly in light of his rapid transition to high-paying roles in the defence and strategic advisory industries after leaving politics. Morrison stepped down as Prime Minister following his coalition’s defeat in the 2022 federal election and formally retired from parliament in February 2024. Almost immediately, he announced his move into the private sector, taking up positions that directly intersect with the defence and security domains he championed while in office. Notably, he joined DYNE Maritime as a strategic advisor, a venture capital firm focused on investing in emerging military technologies with dual-use applications – innovations that serve both civilian and defence purposes. DYNE Maritime, launched with a $157 million fund, explicitly aims to capitalise on opportunities arising from AUKUS, funding startups in areas like undersea drones, AI, and hypersonics that align with the pact’s Pillar II.

In addition, Morrison became the non-executive vice chairman of American Global Strategies, a US-based geopolitical advisory and consulting firm founded by former Trump administration officials. This role involves providing strategic advice on Indo-Pacific security, defence partnerships, and economic policies, topics central to AUKUS. Since taking these positions, Morrison has been active in promoting the pact internationally. In July 2025, he testified before a US Congressional committee, urging continued support for AUKUS and warning against complacency toward China’s threats. He has also spoken at various forums, describing the deal as a critical bulwark against autocratic ambitions and critiquing the current Australian government’s approach to defence spending.

These post-political roles have sparked debate about whether Morrison had a vested interest in securing AUKUS during his tenure. Critics argue that the revolving door between politics and industry creates an incentive for leaders to pursue policies that benefit future employers. In Morrison’s case, his instrumental role in forging AUKUS – negotiating in secrecy for 18 months with limited cabinet involvement – positioned him as an expert with insider knowledge, making him highly valuable to firms profiting from the pact. For instance, DYNE Maritime’s focus on AUKUS-related technologies means Morrison’s involvement could leverage his connections and insights to attract investments and secure contracts. Similarly, American Global Strategies benefits from his experience in US-Australia relations, potentially advising clients on navigating the alliance’s opportunities.

While there is no direct evidence that Morrison pursued AUKUS explicitly for personal financial gain, the optics are troubling. His ministerial code of conduct, which he enforced as Prime Minister, stipulated an 18-month cooling-off period for former ministers to avoid lobbying or business dealings related to their portfolios. Although Morrison’s roles began after this period, critics contend that the spirit of the code is violated when a leader profits from a signature policy like AUKUS. Transparency International Australia has expressed concern, noting that such moves could undermine public trust in government procurement, especially for a $368 billion deal. Morrison’s predecessors, like former Defence Minister Christopher Pyne and Ambassador Joe Hockey, have similarly transitioned to AUKUS-linked ventures, highlighting a pattern in Australian politics.

Defenders of Morrison point to his longstanding hawkish stance on China, predating AUKUS, as evidence of genuine strategic conviction rather than self-interest. As Immigration Minister, he implemented Operation Sovereign Borders, and as Treasurer, he oversaw economic measures amid rising tensions with Beijing. His post-political activities, including receiving the Companion of the Order of Australia in June 2025 for contributions to national security via AUKUS, are framed as continuations of public service. Morrison himself has dismissed criticisms, arguing that his expertise benefits global security efforts.

Nevertheless, the lucrative nature of these roles – estimated to earn him significantly more than his parliamentary salary – fuels speculation. Reports suggest Morrison’s advisory positions could command six-figure fees for speeches and consultations, amplified by his AUKUS legacy. This raises broader ethical questions: Does the prospect of post-political windfalls influence policy decisions? In Morrison’s case, the secrecy surrounding AUKUS negotiations – kept from most cabinet members until late stages – might have minimised scrutiny, allowing a deal that aligns with industries he later joined. While not illegal, this dynamic erodes confidence in leadership, suggesting AUKUS was as much about personal legacies and future opportunities as national interest.

Ultimately, whether Morrison’s vested interests drove the deal remains speculative, but the correlation between his policy achievements and career trajectory warrants scrutiny. It underscores a systemic issue in Australian politics, where the absence of stricter post-office restrictions allows such transitions, potentially prioritising individual gain over collective welfare.

The Staggering Costs of AUKUS

One of the most glaring issues with AUKUS is its astronomical cost, estimated at up to $368 billion AUD over three decades – the largest defence expenditure in Australian history. This figure, announced in 2023, covers submarine acquisition, infrastructure, training, and sustainment, but experts warn it could escalate due to inflation, currency fluctuations, and unforeseen delays. By mid-2025, Australia has already disbursed significant payments, including a second $525 million USD instalment to the US for industrial base enhancements, despite ongoing reviews under Trump.

Breaking it down, the deal requires Australia to invest $3 billion USD in US shipyards to boost Virginia-class production, essentially subsidising American industry. Domestic costs include upgrading facilities in Adelaide and establishing nuclear waste storage, potentially adding billions more. The government’s defence budget, currently around 2% of GDP, may need to rise to 3.5% to meet commitments, as warned by the Pentagon in 2025. This strains public finances, diverting funds from healthcare, education, and climate resilience – priorities for a nation facing cost-of-living crises.

Comparatively, the scrapped French deal was valued at $90 billion for 12 submarines, offering immediate capability without nuclear risks. AUKUS’s price tag equates to roughly $46 billion per submarine, far exceeding alternatives like Japan’s Soryu-class ($500 million each) or enhanced Collins-class upgrades. Opportunity costs are immense: $368 billion could fund universal dental care for decades or build renewable energy infrastructure to combat climate threats more pressing than hypothetical conflicts. For context, Australia’s annual healthcare budget is about $200 billion; reallocating even a fraction from AUKUS could address chronic underfunding in mental health services or aged care.

Moreover, the costs extend beyond direct spending. Training Australian personnel in nuclear operations requires sending hundreds to the US and UK, incurring relocation and expertise-building expenses. Infrastructure upgrades, such as expanding Stirling Naval Base in Western Australia, involve environmental assessments and community disruptions, adding hidden costs. Inflation in defence sectors, exacerbated by global supply chain issues post-COVID, has already pushed estimates upward. A 2024 audit by the Australian National Audit Office highlighted risks of cost overruns, citing poor initial planning under Morrison’s government.

Proponents claim the investment yields long-term deterrence value, but economic analyses suggest otherwise. Think tanks argue AUKUS lacks transparency and parliamentary scrutiny, labelling it “poor governance.” With Trump’s tariffs looming, potentially adding extra costs on imported components, Australia risks funding a phantom fleet. In fiscal terms, AUKUS is not an investment but a gamble, betting taxpayer dollars on unproven promises. The burden falls disproportionately on future generations, who will inherit the debt without guaranteed benefits.

To illustrate, consider the US Navy’s own struggles: Virginia-class submarines have faced production delays and budget blowouts, with each boat costing over $4 billion USD. Australia, as a junior partner, may bear disproportionate escalation risks. Domestic manufacturing in Adelaide promises jobs – estimated at 20,000 – but these are offset by higher wages in specialised nuclear fields and potential union disputes. Critics like economists from the Australia Institute point out that similar funds invested in green technologies could create more sustainable employment while addressing existential climate risks.

In summary, the staggering costs of AUKUS threaten Australia’s economic stability, diverting resources from pressing domestic needs and exposing the nation to inflationary pressures and foreign dependencies.

The Strong Possibility of No Submarines Ever Being Delivered

Beyond costs, AUKUS’s delivery timeline is fraught with risks, making it increasingly likely Australia receives few – if any – submarines. The plan hinges on the US selling three to five Virginia-class boats in the 2030s, but US Navy production lags severely. As of 2025, the US produces only 1.2 submarines annually, far below the required two-plus to meet its own needs and exports. Admiral Lisa Franchetti warned in July 2025 that sales to Australia depend on doubling production, a goal hampered by workforce shortages and supply chain issues.

Trump’s review exacerbates uncertainty. Initiated post-inauguration, it scrutinises whether AUKUS aligns with US interests, with leaks suggesting potential cancellation or renegotiation. Trump’s ignorance – famously asking “What does that mean?” about AUKUS – signals low priority. Industrial crises in the US and UK, including delays in the SSN-AUKUS design, push full delivery into the 2050s, leaving Australia with a capability gap as Collins-class subs retire.

Geopolitical shifts add layers: Rising US-China tensions mean the US may prioritise its fleet, as noted by experts. Australia’s interim measures, like hosting allied subs from 2027, offer no ownership, merely rotational presence. Critics like former Foreign Minister Gareth Evans argue the deal is “dead,” with no realistic path to fruition. The UK component faces similar hurdles, with its Astute-class program over budget and delayed.

Technical challenges abound. Nuclear propulsion requires Australia to develop expertise from scratch, including stewardship of highly enriched uranium, raising proliferation concerns. Delays in US shipyards, such as Huntington Ingalls and General Dynamics, stem from post-pandemic labour shortages – over 100,000 workers needed industry-wide. A 2025 US Government Accountability Office report highlighted these bottlenecks, predicting further slips.

If deliveries fail, Australia faces a defence vacuum. The Collins-class, extended via life-of-type upgrades, will be obsolete by the 2040s, vulnerable to modern anti-submarine warfare. Alternatives like leasing submarines were dismissed, but now seem prudent. Without submarines, Australia squanders billions on infrastructure and training for non-existent assets, undermining defence readiness.

The possibility of non-delivery isn’t hypothetical; historical precedents like the F-111 aircraft deal in the 1960s saw massive delays and costs. AUKUS risks repeating this, with Australia locked in without exit clauses. As Trump priorities domestic manufacturing, export approvals could stall, leaving Canberra humiliated and under-equipped.

Loss of Sovereignty

AUKUS profoundly erodes Australian sovereignty, entangling the nation in US strategic imperatives. By adopting US nuclear propulsion technology, Australia becomes dependent on American maintenance, fuel, and approvals, effectively ceding control over its submarine fleet. Former Foreign Minister Bob Carr described it as a “colossal surrender,” where Australia lacks agency in operations or cancellations.

The pact mandates hosting US bases and submarines, turning Australian soil into extensions of American power projection. This includes nuclear waste storage, raising environmental and proliferation risks without full parliamentary debate. Critics argue it entraps Australia in potential US-China conflicts, with decisions made in Washington, not Canberra. Turnbull and Keating warn of an “affront to sovereignty,” as AUKUS flexibility favours the US/UK, allowing unilateral withdrawal. In 2025, Trump’s demands for higher defence spending (3.5% GDP) underscore this imbalance. The deal’s secrecy under Morrison limited debate, binding future governments.

Sovereignty loss extends to technology sharing: Pillar II requires aligning with US export controls, potentially restricting Australia’s independent R&D. Hosting rotations from 2027 integrates Australian forces under US command structures, blurring operational autonomy. Historically, alliances like ANZUS preserved sovereignty, but AUKUS’s depth – sharing nuclear secrets – creates unprecedented dependency. Australia forfeits flexibility in foreign policy, compelled to echo US stances on issues like Taiwan. This dependency contradicts Australia’s independent foreign policy tradition, prioritising alliance over autonomy. Reclaiming sovereignty demands reevaluating AUKUS, perhaps through multilateral forums like ASEAN.

Damaging Trade Relations with China

AUKUS has strained Australia’s ties with China, its largest trading partner, jeopardising economic prosperity. China views the pact as provocative, aimed at containment, leading to diplomatic freezes and trade barriers post-2021. By 2025, while some relations thawed – two-way trade reaching $312 billion in 2024 – suspicion lingers, with Beijing criticising AUKUS as destabilising.

Former PM Scott Morrison noted China’s coercive trade policies targeted Australia as a US ally example. Iron ore, coal, and wine exports suffered, costing billions. Hawks ignore how China trade funds AUKUS, creating irony. In 2025, Trump’s tariffs could compound this, forcing Australia to choose between security and economy.

The pact escalates tensions without necessity; Australia’s economy relies on China for 30% of exports. Bans on barley and lobster in 2020-2021 cost $20 billion, hitting rural communities hard. Diplomatic charm offensives under Albanese eased some barriers, but AUKUS revives distrust.

Alternatives like diversified trade – to India or Vietnam – could mitigate, but AUKUS hinders this by signalling hostility. Economic modelling shows potential GDP losses of 1-2% if relations sour further. Australia must balance security with prosperity, not sacrifice one for the other.

Cheaper and Better Options Available

Viable alternatives to AUKUS exist, offering superior value. The French Suffren-class, smaller and cheaper, provides nuclear capability without US dependency. Japanese Soryu-class diesel subs, at $500 million each, are stealthy and proven. Missiles and drones form an “echidna strategy” for asymmetric defence, costing far less. Upgrading Collins-class with air-independent propulsion bridges gaps affordably. Sweden’s Gotland-class or South Korea’s KSS-III offer hybrid options, blending diesel efficiency with nuclear-like endurance. These preserve sovereignty and align with Australia’s needs.

Drone swarms, like US Replicator program, provide cost-effective deterrence at fractions of submarine costs. Investing in hypersonics or cyber capabilities enhances defence without nuclear risks. A mixed fleet – diesel subs plus unmanned vessels – delivers flexibility. AUKUS overlooks these, locking into an expensive, uncertain path. Cheaper options allow reallocating funds to social programs, boosting overall resilience.

Trump’s Notorious Disregard for Treaties

Trump’s history of abandoning agreements – Paris Accord, TPP, Iran deal – bodes ill for AUKUS. In 2025, his review questions the pact’s value, with statements like “What does that mean?” revealing disinterest. Despite some support from aides, Trump’s “America First” prioritises US gains, potentially demanding concessions or scrapping it.

Trump’s first term saw erratic alliances. Allies like Australia were pressured for more contributions. AUKUS, requiring US tech transfer, clashes with his protectionism. If US production can’t meet demands, Trump may halt sales, citing national security. This unpredictability amplifies risks; Australia lacks leverage, having invested billions.

Conclusion

Trump’s Mar-a-Lago ties with Morrison offer no guarantee, as personal relationships yield to politics. Exiting AUKUS now avoids deeper entanglement in Trump’s volatility. It is a bad deal for Australia, marred by costs, delivery doubts, sovereignty loss, trade damage, overlooked alternatives, and Trump’s unreliability. Morrison’s post-political gains highlight potential conflicts, underscoring need for reform. Exiting safeguards interests, redirecting resources wisely. Australia must forge an independent path.