In the summer of 2025, a collection of artefacts from Richmond, Virginia, the former capital of the Confederacy, embarked on a cross-country journey to the Museum of Contemporary Art (MOCA) in Los Angeles. These items, including a globe from a monument to Confederate naval officer Matthew Fontaine Maury, the granite base of the Jefferson Davis monument, a statue of Vindicatrix (an allegorical figure symbolising the South’s vindication), and various granite slabs, join decommissioned statues and relics from cities like Baltimore, Charlottesville, New Orleans, and Raleigh, North Carolina, in an exhibition titled “MONUMENTS.” Facilitated by the Black History Museum and Cultural Centre of Virginia (BHMVA), which assumed ownership of Richmond’s removed Confederate memorials in 2022, this move has reignited a familiar debate: Are we erasing history by dismantling these symbols, or are we finally explaining it in a way that honours truth over myth?

The “MONUMENTS” exhibition, co-organised by MOCA and The Brick and co-curated by artists and scholars including Kara Walker and Hamza Walker, presents these artefacts not as glorified icons, but as objects in varying states of disrepair, some vandalised, others intact, alongside contemporary artworks by creators like Bethany Collins, Abigail DeVille, and Hank Willis Thomas. The show reflects on the legacies of post-Civil War America, highlighting how these statues evolved from modest memorials to potent symbols of white supremacist ideology, particularly during the rise of Jim Crow and resistance to civil rights. Far from being tucked away to be forgotten, these relics are recounted recontextualised in a museum setting, where visitors engage with their complex histories through educational programming, scholarly publications, and artistic interpretations. This approach transforms symbols of oppression into tools for dialogue, fostering understanding without endorsement.

This development comes as America grapples with its past. Since the murder of George Floyd in 2020, which sparked nationwide protests against racial injustice, over 200 Confederate symbols have been removed from public spaces across the United States. In Richmond, protesters toppled the Jefferson Davis statue, prompting then-Mayor Levar Stoney to order the removal of 15 city-owned memorials. In 2021, Virginia dismantled the massive Robert E. Lee statue on state-owned property, deeding it to the city. Opponents of these actions often cry “erasure,” arguing that removing statues disrespects Southern heritage or whitewashes uncomfortable truths. However, as the LA exhibition demonstrates, relocation to museums is not about eradication, it’s about explanation, stripping away the romanticised veneer that has obscured the realities of slavery, secession and systemic racism.

To understand why this matters, we must explore the origins of these monuments. They were not erected immediately after the Civil War as simple tributes to the fallen. Most emerged in the early 20th century, around the 50th anniversary of the conflict, during a period when the South reinvented its narrative through the “Lost Cause” mythology. Propagated by Confederate veterans, their descendants, and organisations like the United Daughters of the Confederacy (UDC), this narrative recast the war as a noble stand against federal overreach, a righteous rebellion for states’ rights and Southern honour, while downplaying or omitting slavery entirely. Tales of chivalrous generals and devoted soldiers replaced the brutal reality of a war fought to preserve human bondage.

The Lost Cause was more than a story; it was a cultural and political tool. Emerging in the late 1860s and formalised by groups like the Southern Historical Society in 1869, founded by figures like Braxton Bragg and Jubal Early, it justified the end of Reconstruction and the rise of Jim Crow laws that disenfranchised Black Americans and enforced segregation. Women played a pivotal role, leading memorial associations and fundraising for statues, often framing their efforts as apolitical acts of mourning. Yet, these monuments, built between 1890 and 1920 during the nadir of race relations, became physical assertions of white dominance, coinciding with lynchings and Black voter suppression. A second wave of monuments in the 1950s and 1960s, during resistance to the Civil Rights Movement, further entrenched their role as symbols of defiance.

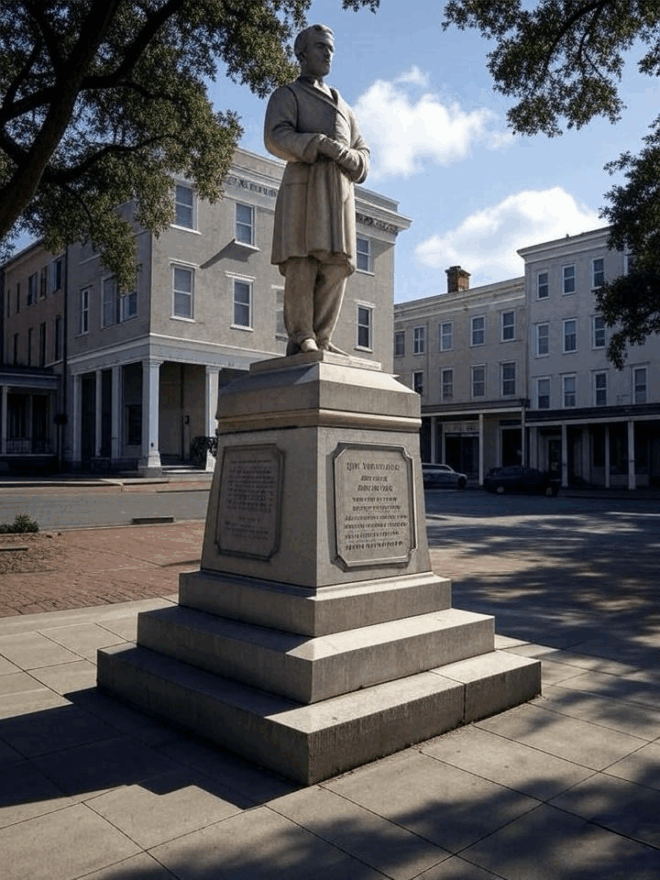

Richmond’s Monument Avenue, unveiled in 1890 with the Lee statue, became a grand boulevard lined with equestrian figures of Confederate leaders like Stonewall Jackson (1919), JEB. Stuart (1907), and Jefferson Davis (1907). These were not neutral historical markers; they were designed to inspire awe and loyalty to a sanitised version of the past, where the Confederacy’s defeat was tragic, but its cause pure. Over 700 such monuments still stand today, often near sites of racial violence, like the 130 in Mississippi alone. The Confederate battle flag, another Lost Cause emblem, flew over state capitols until recent decades, symbolising not just heritage, but opposition to integration.

Historians like Karen Cox, author of “Dixie’s Daughters,” argue that the UDC and similar groups shaped public memory to align with white supremacist ideals. Textbooks influenced by Lost Cause proponents taught generations that the war was about tariffs or abstract principles, not slavery. Monuments reinforced this narrative, standing in courthouse squares, parks and campuses as reminders that the South’s “heroes” deserved veneration. This revisionism marginalised Black voices, perpetuating inequality by erasing the experiences of enslaved people and their descendants. Protests against these monuments date back to their installation, with Black communities viewing them as tools of intimidation, yet the Lost Cause narrative held sway for over a century, allowing statues to masquerade as objective history.

The 21st century brought a turning tide, accelerated by events exposing America’s racial divides. The 2015 Charleston church shooting, where a white supremacist murdered nine Black worshippers, prompted the removal of the Confederate flag from South Carolina’s statehouse. The 2017 Unite the Right rally in Charlottesville, sparked by plans to remove a Lee statue, highlighted how these symbols attract extremist groups. George Floyd’s death in 2020 catalysed a nationwide reckoning, with protesters targeting monuments as embodiments of systemic racism. In Baltimore, four Confederate statues were removed overnight in 2017. New Orleans dismantled its Lee, Davis and PGT Beauregard monuments amid threats of violence. Raleigh saw protesters pull down statues at the state capitol. In Richmond, Monument Avenue transformed into a site of protest art, with graffiti and projections turning pedestals into canvases for Black Lives Matter messages.

By 2022, Richmond transferred ownership of its monuments to the BHMVA, which consulted communities on their future. These actions were deliberate efforts to reclaim public spaces from symbols glorifying treason and oppression. The BHMVA’s decision to loan artefacts to MOCA reflects a commitment to preservation with purpose. Museums, unlike public squares where statues loom unchallenged, are dynamic environments designed for inquiry. They allow artefacts to be studied, not worshipped, presenting them alongside primary sources, oral histories and contemporary perspectives. The MOCA exhibition, for instance, displays the vandalised Jefferson Davis monument base next to artworks like Kara Walker’s Silhouettes exploring racial violence or Hank Willis Thomas’s pieces on Identity. This curatorial choice underscores how these objects shifted from funerary markers to tools of ideology, inviting viewers to question who controls historical memory.

Community responses to these relocations reveal the polarised views on Confederate symbols. In Richmond, public forums hosted by the BHMVA heard from older white Southerners who mourned the loss of Monument Avenue’s statues, seeing them as ties to family histories or regional pride. Some shared stories of ancestors who fought for the Confederacy, framing their actions as personal sacrifice rather than ideological endorsement. Meanwhile, Black residents and younger activists celebrated the removals, describing how passing these statues daily felt like a silent endorsement of oppression, reinforcing generational trauma. These dialogues highlight the challenge of reconciling individual heritage with collective harm, but the BHMVA’s inclusive approach shows how communities can prioritise education over erasure.

Opponents of removal raise concerns framed in terms of heritage and history. They argue that statues honour ancestors who fought bravely, regardless of the cause, and that removing them disrespects Southern culture. “It’s not about hate; it’s about history,” is a common refrain, with some claiming monuments educate about the past. Others fear a slippery slope: if Confederates today, who’s next, Washington or Jefferson, who owned slaves? Legal hurdles also exist, as some Southern states passed laws protecting these memorials, viewing removal as vandalism. One commentator suggested that fearing old statues distracts from real-time hatred on social media. For many, these figures represent family legacies, grandfathers who were poor farmers, not slaveholders, fighting for home and hearth.

These arguments carry weight in a pluralistic society. History is multifaceted, and blanket condemnations can alienate those who see the Confederacy through a personal, non-racist lens. Some worry that removal oversimplifies the past, turning nuanced figures like Lee, who opposed slavery in some writings but fought for it, into caricatures. If we tear down everything imperfect, what’s left? Proponents of keeping statues often advocate for adding context, like plaques explaining the full story, rather than destruction.

However, these defences often overlook the monuments’ inherent bias. They were not built to teach balanced history but as propaganda for the Lost Cause, omitting slavery’s centrality to secession. Removing them corrects history by acknowledging their role as reminders of slavery and systemic racism without explanation. In public spaces, they inflict harm on Black communities, serving as unavoidable symbols of subjugation. Historians note that many were erected to intimidate during Jim Crow and civil rights eras, not just to mourn. Keeping them honours a false narrative, perpetuating division.

Museums offer an ideal solution: They explain without endorsing. Unlike street corners, museums provide context through curatorial notes, artefacts, and dialogues. The MOCA exhibition exemplifies this, inviting visitors to reflect on how these objects became tools of ideology. Similar efforts, like the National Museum of African American History and Culture’s displays on Reconstruction, show how relocation educates without glorification. Museums also mitigate the risk of destruction. Many removed statues, if left in storage, face vandalism or decay, which could erase their historical value. With conservation expertise, museums ensure these artefacts endure as primary sources, not idols. The Maury monument’s globe, for instance, now tells a story of naval history and Confederate myth-making, paired with documents revealing Maury’s defence of slavery.

The broader implications extend to education and public memory. Schools influenced by Lost Cause myths have long skewed curricula; removing public endorsements encourages truthful teaching about slavery’s horrors, the war’s causes, and Reconstruction’s failures. In Virginia, post-removal initiatives include renaming schools and streets after Black heroes, balancing the narrative. This isn’t erasure—it’s expansion, including voices of enslaved people, Union soldiers, and civil rights activists. Museums democratise memory, allowing multiple perspectives to coexist. The MOCA exhibit includes voices from artists, historians, and descendants of enslaved people, creating a polyphonic narrative absent from the original monuments. Globally, similar approaches, Germany preserving Nazi-era artefacts in museums, or South Africa relocating apartheid-era statues, foster understanding without glorification.

Legal and ethical dimensions add complexity. Some state constitutions emphasise unity post-Reconstruction, yet protecting monuments contradicts that. Ethically, public spaces should reflect shared values like equality, not division. Practically, museums preserve artefacts safely, preventing vandalism while allowing study. The LA exhibition, opening amid ongoing debates, models this approach. By loaning items, the BHMVA transforms symbols of oppression into educational tools, fostering dialogue across divides.

Ultimately, moving Confederate monuments to museums is not about eradicating history, but explaining it honestly. It confronts the Lost Cause’s lies, centres truth, and builds a more inclusive future. As America evolves, so must its memorials, honouring all stories, not just the victors’ myths. By preserving these artefacts in spaces designed for inquiry, we ensure history is remembered better, fostering reconciliation without sacrificing truth.