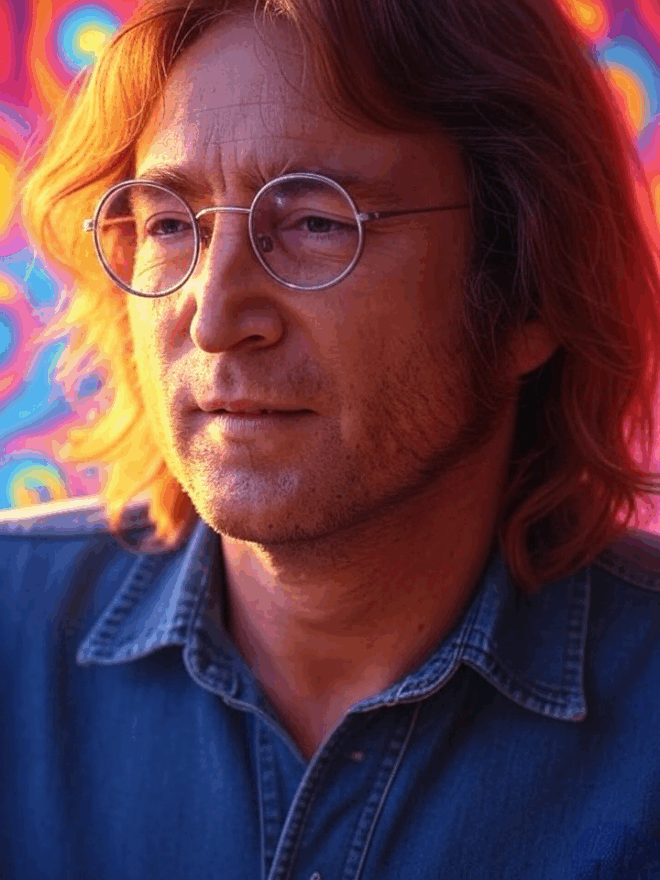

“My role in society, or any artist’s or poet’s role, is to try and express what we all feel. Not to tell people how to feel. Not as a preacher, not as a leader, but as a reflection of us all.”

John Lennon

Introduction

Artists have long served as the conscience of society, wielding their brushes, pens, and voices to reflect the world as it is, often unflinchingly and at great personal cost. The role of the artist, as articulated by thinkers like James Baldwin, is to “illuminate that darkness, blaze roads through that vast forest, so that we will not, in all our doing, lose sight of its purpose, which is, after all, to make the world a more human dwelling place.” This mirrors the ancient Egyptian scribes who critiqued pharaohs through subtle carvings, or the protest art of the 20th century that challenged racial injustice and war. Yet, in an era where critique can invite ostracism, cancellation, or worse, the artist’s duty remains: to hold a mirror to society without fear.

This essay explores this artistic imperative through a contemporary lens: the complex interplay between Zionism and Judaism, the necessity of fair criticism of Israel, and the stark reality of famine in Gaza amid accusations of fabrication. These issues are intertwined in a global discourse fraught with emotion, misinformation and partisan divides. Zionism, a political ideology born in the late 19th century amid European nationalism and antisemitism, is not synonymous with Judaism, a millennia-old religion rooted in ethical monotheism and spiritual practice. Conflating the two not only distorts history but also stifles legitimate critique of Israeli policies, as no nation should be immune from scrutiny. Furthermore, the famine ravaging Gaza is no staged spectacle, termed “Pallywood” by detractors, but a documented humanitarian catastrophe exacerbated by conflict and blockades. Artists, from Palestinian poets to international filmmakers, play a vital role in unveiling these truths, challenging societies to confront uncomfortable realities. Through a truth-seeking, non-partisan examination, this essay argues that embracing artistic critique fosters empathy and justice, essential for resolving such entrenched conflicts.

The Artist as Societal Mirror: Historical and Contemporary Roles

Art has never been mere decoration; it is a weapon against complacency. The earliest protest art emerged in ancient Egypt, where artisans subtly critiqued pharaohs’ excesses through tomb carvings that highlighted social inequalities. This tradition evolved through centuries: Renaissance painters like Hieronymus Bosch depicted societal vices in grotesque detail, while 19th-century realists such as Honoré Daumier satirised corruption in French society. In the 20th century, art became overtly activist. Pablo Picasso’s Guernica (1937) immortalised the horrors of fascist bombing during the Spanish Civil War, forcing viewers to confront the brutality of modern warfare. Similarly, during the American Civil Rights Movement, artists like Jacob Lawrence captured the struggles of Black Americans, holding a mirror to racial injustice without fear of backlash.

James Baldwin, in his essay “The Creative Process,” articulated the artist’s role explicitly: “The precise role of the artist, then, is to illuminate that darkness… so that we will not, in all our doing, lose sight of its purpose.” Baldwin himself faced ostracism for critiquing American racism, yet his work endures as a testament to unflinching truth-telling. In more recent times, protest art has challenged political systems globally. The alter-globalisation movement saw artists in tactical media groups decorating protests with subversive imagery, blending art and activism to critique neoliberalism. During the AIDS crisis, collectives like ACT UP used graphic posters to expose governmental neglect, saving lives through visual confrontation.

Critique without fear is paramount, as censorship breeds stagnation. In authoritarian regimes, artists like Ai Weiwei in China or Banksy in the West, risk imprisonment or exile to expose truths. Banksy’s murals on the Israeli separation wall, depicting children escaping via ladders or balloons, critique occupation without equating it to Judaism, focusing instead on human rights. Yet, fear of ostracism persists: in the U.S., artists criticising Israeli policies often face accusations of antisemitism, leading to canceled exhibitions or lost funding. This mirrors McCarthy-era suppression, where artists were blacklisted for “un-American” views. As one critic notes, “Artists must be free to offend… without fear or favour.”

In the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, artists like Palestinian filmmaker Elia Suleiman or Jewish-American cartoonist Art Spiegelman use satire and memoir to critique power structures. Suleiman’s Divine Intervention (2002) mirrors absurdities of occupation, while Spiegelman’s Maus explores Holocaust trauma without endorsing Zionism. These works underscore that art’s mirror reflects societal flaws, urging reform. Without such critique, societies risk moral atrophy, as seen in Orwell’s warnings about truth’s erosion.

Distinguishing Zionism from Judaism: Historical and Ideological Foundations

Zionism and Judaism are often conflated in public discourse, yet they are fundamentally distinct. Judaism is an ancient religion, dating back over 3,000 years, centred on monotheism, ethical laws (halakha), and spiritual practices derived from the Torah, Talmud, and prophetic traditions. It emphasises justice, compassion and the pursuit of peace, as in the commandment “Love thy neighbour as thyself” (Leviticus 19:18). Zionism, conversely, emerged in the late 19th century as a secular political movement led by Theodor Herzl, responding to European antisemitism and nationalism. It advocated for a Jewish homeland in Palestine as a solution to the “Jewish Question,” framing it as national self-determination.

Not all Jews are Zionists; historical opposition was widespread. Orthodox Jews, like those in Neturei Karta, view Zionism as heretical, believing Jewish return to Israel must await the Messiah. Reform Jews initially rejected it as incompatible with assimilation, while Bundists (Jewish socialists) prioritised class struggle over nationalism. As Rabbi Yisroel Dovid Weiss states, “Zionism is not Judaism… It was a political movement founded in Europe.” Today, groups like Jewish Voice for Peace embody anti-Zionist Judaism, advocating Palestinian rights based on tikkun olam (repairing the world).

The conflation arises from Israel’s self-presentation as the “Jewish state,” but this is misleading. Zionism colonised Palestine, displacing Indigenous Arabs, in a process akin to European settler-colonialism. Early Zionists like Herzl envisioned a “European outpost” in the Middle East, ignoring Palestinian presence. This ideology, not Judaism, underpins Israel’s policies. Equating them weaponises antisemitism accusations against critics, as seen in debates over the IHRA definition, which includes examples blurring anti-Zionism with Jew-hatred.

Scholars like Edward Said critiqued Zionism as Orientalist, denying Palestinian agency. Norman Finkelstein documents Jewish anti-Zionists opposing it on ethical grounds. Conflation endangers Jews by tying their safety to Israel’s actions, fuelling backlash. As one analysis notes, “Conflating Zionism with Judaism is antisemitic” because it holds all Jews accountable for state policies.

Artists challenge this: Palestinian rapper Tamer Nafar’s lyrics distinguish “Zionist occupation” from Judaism, while Jewish playwright Tony Kushner critiques Israel without self-hatred. Such distinctions enable honest dialogue, fulfilling art’s mirroring role.

The Inappropriateness of Conflating Zionism and Judaism

Conflating Zionism with Judaism is not only historically inaccurate but ethically dangerous, as it stifles debate and misuses antisemitism. Antisemitism is hatred of Jews qua Jews; discrimination, stereotypes, violence. Anti-Zionism critiques a political ideology supporting Israel’s establishment and policies. As Peter Beinart argues, “Debunking the myth that anti-Zionism is antisemitic” is crucial, since many Jews oppose Zionism.

This conflation serves political ends: Israel’s supporters label critics antisemitic to deflect scrutiny. The U.S. House resolution equating anti-Zionism with antisemitism exemplifies this, denounced as “dangerous” for chilling speech. It echoes McCarthyism, where dissent is treasonous. Historically, Zionism’s founders were secular; Herzl was agnostic, viewing Judaism as cultural, not religious. Religious Jews like Satmar Hasidim reject Israel as premature redemption.

Conflation harms Jews: it implies all support Israel’s actions, inviting collective blame. As one Jewish historian notes, “When does anti-Zionism become antisemitism? A Jewish historian’s perspective” requires nuance, demonising Jews crosses the line, but denying Israel’s right to exist (as a settler state) does not inherently. Surveys show Israeli society divided on religion’s role, with secular Jews dominating Zionism.

Artists counter this: Films like No Other Land (2024) document West Bank occupation without antisemitism, yet faced “Pallywood” smears. By separating Zionism from Judaism, art promotes understanding, as in Rabbi Weiss’s speeches: “Zionism is not Judaism.”

Israel and the Imperative of Fair Criticism

No country is above criticism; immunity breeds impunity. Israel, like any nation, must face scrutiny for policies violating international law, such as settlements or Gaza blockades. Fair criticism targets actions, not identity. The “3Ds” test: denomination, double standards, delegitimisation, helps distinguish critique from antisemitism. Questioning settlements as illegal (per UN resolutions) is legitimate; calling Israel “demonic” is not.

Critics like Amnesty International label Israel’s system “apartheid,” based on evidence of discrimination. Many Jews, including B’Tselem, agree. Yet, such reports invite antisemitism charges, as in Kansas’s law defining criticism as hate. This chills speech, contradicting democratic values.

Historical parallels: South Africa’s apartheid faced boycotts; Israel’s BDS movement is similarly smeared. As the Anne Frank House notes, “All criticism of Israel [is not] antisemitic,” but denying its existence might be. Artists amplify this: Banksy’s works critique walls and checkpoints, fostering empathy.

Fair criticism promotes peace; silencing it perpetuates conflict.

The Reality of Famine in Gaza: Beyond Pallywood Accusations

The famine in Gaza is a grim reality, not fabrication. As of August 2025, UN-backed IPC reports confirm famine thresholds met: over 1.1 million face catastrophic hunger (Phase 5), with 98 child deaths from malnutrition since July. IPC data shows 96% of Gazans in acute food insecurity, with thresholds for consumption and malnutrition exceeded. UN Secretary-General António Guterres calls it “starvation, pure and simple,” urging ceasefire and aid.

“Pallywood” – a derogatory term alleging staged suffering – dismisses this evidence. Originating from claims like the al-Durrah incident, it’s used to discredit Palestinian narratives. Fact-checkers debunk many: videos of “staged” famine are from unrelated events or misidentified. German media accused photographers of staging, but investigations rebutted, confirming authenticity. While some images are taken out of context, they don’t negate IPC’s cross-verified data.

Causes: Blockades, conflict disrupt aid; Hamas diversion allegations exist, but UN attributes primary responsibility to restrictions. Over 60,000 killed, 1.9 million displaced exacerbate crisis. Artists document this: Photographers like Mahmod Hinawi capture hunger’s toll, holding mirrors to global indifference.

Denying famine via “Pallywood” is disinformation, undermining humanitarian response. Truth-seeking demands acknowledging evidence.

Artists Critiquing the Gaza Famine and Broader Conflict

Artists have been pivotal in exposing Gaza’s famine, countering denial. Palestinian photographers document skeletal children scrambling for aid, their images a raw mirror to suffering. Films like No Other Land (2025 Oscar winner) portray occupation’s human cost, facing “Pallywood” smears yet persisting. International artists, like Roger Waters, use music to critique, drawing McCarthy-like backlash.

This mirrors historical art: Goya’s Disasters of War etched famine’s horrors during Napoleonic invasions. In Gaza, street art and poetry – e.g., Refaat Alareer’s “If I Must Die” – immortalise resilience amid starvation.

Without fear, artists blaze paths to empathy, challenging conflations and demanding justice.

Artistic Censorship in Australia Amid the Gaza Conflict

In Australia, the Gaza conflict has precipitated a wave of artistic censorship, exemplifying how fear of ostracism and political pressures can silence voices critiquing Israeli policies or expressing solidarity with Palestinians. This trend underscores the essay’s central thesis: artists must hold mirrors to society without fear, yet institutional and governmental forces often impose barriers, conflating anti-Zionism with antisemitism and stifling free expression.

A prominent case involves artist Khaled Sabsabi, whose invitation to represent Australia at the 2026 Venice Biennale was revoked by Creative Australia in February 2025. Sabsabi, a Lebanese-Australian multimedia artist known for works exploring cultural identity, migration, and resistance, faced backlash after a Murdoch-owned newspaper article accused him of antisemitism.

The controversy centred on his past boycott of the 2022 Sydney Festival over Israeli funding and artworks like “You (2007),” which featured Hezbollah leader Hassan Nasrallah’s speech, interpreted by critics as a critique of Western media portrayals rather than endorsement. Conservative Senator Claire Chandler amplified these claims in parliament, questioning government funding for Sabsabi amid his alleged promotion of “terrorism.” Foreign Minister Penny Wong responded by seeking clarification, accepting the framing without context.

Creative Australia cited “unacceptable risk to public support” for the arts, a decision decried as censorship. The arts community rallied: shortlisted Biennale artists demanded reinstatement, senior staff resigned, and an open letter signed by 4,000 accused the board of bowing to right-wing pressure. This incident reflects broader trends where pro-Israel lobbies and media equate criticism of Israel with antisemitism, as seen in similar firings like ABC journalist Antoinette Lattouf for sharing a Human Rights Watch post on Gaza.

Another stark example occurred at the National Gallery of Australia (NGA) in February 2025, where Palestinian flags on a tapestry in the “Te Paepae Aora’i – Where the Gods Cannot be Fooled” exhibition by the Pacific Indigenous collective SaV?ge K’lub were covered with white fabric. The artwork, incorporating flags and slogans for social justice – including Aboriginal, Torres Strait Islander, and West Papuan symbols, aimed to highlight colonialism’s impacts. Curator Rosanna Raymond labeled the action “censorship,” noting the gallery cited a “high-level security risk” and offered removal or concealment as options. The collective reluctantly agreed, questioning why Palestinian symbols were singled out while others remained. The NGA defended the exhibition’s overall reception but evaded specifics, amid Senate scrutiny of its ties to Creative Australia. This selective editing echoes institutional hypocrisy, as the gallery had previously supported diverse voices but yielded to perceived threats during heightened Gaza tensions.

Literary circles have not been immune, as evidenced by withdrawals from the Bendigo Writers Festival in August 2025. Speakers, including academic Dr. Randa Abdel-Fattah, poet Dr. Evelyn Araluen, and writer Jeanine Leane, pulled out over a code of conduct requiring avoidance of “inflammatory” language and adherence to La Trobe University’s anti-racism plan, which incorporates a definition of antisemitism based on the IHRA framework. Abdel-Fattah described it as mandating “complete self-censorship,” particularly gaslighting for Palestinians discussing Gaza’s genocide. The code, sent days before the event, was seen as restricting criticism of Israel, with Jess Hill noting it aimed to prevent political statements on Gaza. La Trobe’s plan defines antisemitism to include tropes or calls for Israel’s elimination but clarifies policy critiques are not inherently antisemitic. Withdrawals highlighted solidarity and concerns over free speech, with Araluen urging audiences to reconsider events divorced from morality and policy.

These cases illustrate a chilling effect on Australian arts, where pro-Palestine expression invites backlash, often amplified by media and politicians aligning with pro-Israel interests. Institutions like Creative Australia and the NGA, despite past support for diverse art, succumb to pressures, fostering self-censorship. This mirrors global patterns but is acute in Australia, where universities adopt IHRA definitions limiting discourse, and petitions for ceasefires go unheeded. Artists respond through boycotts, open letters, and guerrilla actions, like the no-photo2024 festival amplifying Palestinian photographers excluded from mainstream events. Such resistance affirms art’s role in critiquing society, urging Australia to protect expression without fear, lest it erode democratic values amid the Gaza crisis.

Conclusion: Art as a Catalyst for Truth and Justice

The role of the artist as a societal mirror is not merely a historical artefact but a living imperative, as vital today as in ancient Egypt or during the Civil Rights Movement. Through their unflinching critique, artists like Khaled Sabsabi, Banksy, and Refaat Alareer expose the fault lines of our world, whether the conflation of Zionism with Judaism, the suppression of fair criticism of Israel, the denial of Gaza’s famine, or the censorship stifling voices in Australia. By distinguishing Zionism, a political ideology rooted in 19th-century nationalism, from Judaism, a faith centred on ethical monotheism, artists dismantle dangerous conflations that weaponise antisemitism to silence dissent. By documenting the starvation of 1.1 million Gazans and rejecting “Pallywood” smears, they affirm a humanitarian crisis grounded in UN evidence. By resisting censorship, as seen in Australia’s arts scene, they uphold the principle that no nation, including Israel, should be immune from scrutiny.

This fearless reflection is not without cost. Artists face ostracism, funding cuts, and accusations of hate, yet their persistence; through murals, films, poetry, and boycotts. ignites empathy and demands justice. As James Baldwin envisioned, art’s purpose is to make the world more human, a goal achieved only when critique is free from fear. The Gaza conflict, with its layers of suffering and suppression, underscores this urgency. By holding mirrors to society, artists challenge us to confront truths about power, privilege, and humanity. In doing so, they pave the way for dialogue and reconciliation, fostering a world where justice prevails over division, and truth over silence.