Preamble

I wrote a post today on income disparity at Westpac

Westpac can’t afford to give staff even a CPI salary increases, and is retrenching 3,000 staff, but look at this…

Westpac head of institutional banking Nell Hutton has emerged as the buyer of journalist and author power couple Lisa Wilkinson and Peter FitzSimons’ mansion Ingleneuk in Sydney’s lower north shore for an undisclosed sum close to its $23 million asking price

Scrolling further down my X timeline I discovered post after post bemoaning the failing fertility rates across the United States and Europe.

I then began to wonder about what correlation, if any, there was between a lack of secure employment and falling fertility rates?

Introduction

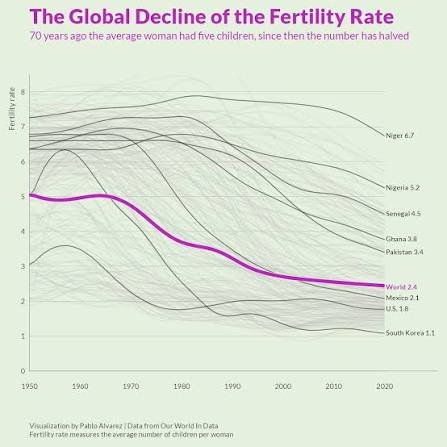

In an age defined by rapid technological change, economic restructuring, and shifting social norms, one demographic trend has quietly, but persistently altered the contours of societies around the world: declining fertility. Where once large families were common and population growth seemed a near certainty, numerous countries now confront fertility rates well below the replacement threshold of approximately 2.1 births per woman. These declines have profound implications for long-term economic growth, the sustainability of pension and healthcare systems, labour market dynamics, and the cultural fabric of nations. Public debates often attribute falling birth rates to cultural change, increased female educational attainment, urbanisation, and the high cost of childrearing. While those factors are undeniably important, an increasingly robust body of evidence points to a less frequently foregrounded but deeply consequential driver: job security, or rather the erosion of it.

Job security is not merely an economic technicality. It is a foundational condition for life planning. The decision to become a parent is among the most consequential that individuals and couples make, entailing long-term commitments of time, money, and emotional labour. When employment is precarious, when contracts are temporary, hours are unpredictable, and the threat of unemployment looms large, the calculus of family formation changes. People delay marriage, postpone first births, opt for fewer children, or forgo parenthood altogether. This post examines the connection between job security and fertility in depth. It synthesises empirical research, explores illustrative national cases, outlines policy interventions that show promise, and considers public perceptions. It also addresses nuance and counterarguments so that readers can appreciate both the strength of the evidence and the complexities inherent in demographic behaviour.

Defining Job Security and Contemporary Labor Market Transformations

To understand how job security affects fertility, it is necessary to clarify what we mean by “job security.” At its core, job security denotes the expectation of stable, long-term employment that provides predictable income, access to social protections such as paid leave and unemployment benefits, and a reasonable prospect of future career progression. It contrasts with precarious employment arrangements characterised by fixed-term contracts, part-time or irregular hours, limited or no benefits, low bargaining power, and high turnover. Job security is thus a blend of contractual formality, institutional protections, and subjective perceptions of future employment prospects.

Over recent decades, labour markets in many advanced economies have undergone profound shifts. Globalisation, technological automation, and the weakening of collective bargaining frameworks in some contexts have combined to produce a phenomenon often labelled “labour market dualization.” In this dynamic, a core of workers – often in older cohorts or in particular sectors – enjoy relatively secure, well-compensated employment, while a growing share of the workforce, particularly younger workers, migrants, and those in service-oriented or technologically mediated occupations, experience precariousness. The rise of gig economy models, platform-mediated contracting, and short-term project work has further blurred the lines between employment and self-employment, frequently stripping workers of protections that once accompanied traditional employment relationships. The International Labour Organisation estimates that a substantial portion of the global labour force remains in vulnerable employment, a figure that has been amplified by cyclical economic shocks and structural adjustment policies.

These transformations matter for demographic decisions. Parenthood typically requires foresight and the expectation that one’s income stream will be sufficiently stable to support long-term childrearing costs. When jobs are insecure, individuals and couples face higher perceived and real risks in embarking on this commitment. Beyond calculations about income, job insecurity imposes psychological costs: heightened stress, reduced life satisfaction, and a diminished sense of control over the future. These effects combine to make the prospect of children less attractive or less feasible for many people.

Empirical Evidence Connecting Job Insecurity and Fertility

The link between job insecurity and fertility is not merely plausible; it is empirically substantiated across diverse contexts. Economists and demographers have employed a range of methodological approaches – including difference-in-differences, instrumental variables, natural experiments, and panel data analysis – to isolate the causal effects of employment instability on childbearing decisions.

One instructive example comes from France, where a policy reform in 2002 altered the employment landscape for a subset of workers and provided researchers with quasi-experimental variation. Analysts found that those exposed to increased risk of layoffs experienced a measurable decline in fertility, particularly in the number of additional children beyond the first. This pattern suggests that insecurity tends to reduce births at the intensive margin, as families opt not to expand rather than foregoing parenthood altogether.

Portugal offers a contrastive example where policy interventions that increased contract stability yielded beneficial demographic effects. Reforms converting long-duration fixed-term contracts into permanent positions, alongside incentives that reduced the use of precarious short-term contracts, were associated with declines in childlessness and increases in second-child births. These findings highlight how legal and institutional changes to contract structures can influence family planning decisions.

Spain’s experience following regularization programs for undocumented immigrants is also illustrative. When large numbers of previously undocumented workers received formal work permits, enabling greater labour market access and reduced deportation risk, fertility rates among affected groups rose. The effect was concentrated among young adults making transitions to second children, reinforcing the idea that security and the ability to plan materially affect decisions to expand families.

Cross-country analyses corroborate these case studies. Panel data across OECD countries show that increasing labour market insecurity tends to coincide with fertility declines. In Germany, sectors and regions that provide more stable employment – such as public services – show relatively higher fertility rates, while areas dominated by cyclical, insecure employment lag behind. In China, the upheaval of state-owned enterprise restructuring during the 1990s led to substantial layoffs and was associated with delayed first births in urban areas and reductions in short-term fertility.

Beyond macro associations, micro-level surveys reveal that subjective perceptions of job uncertainty matter. Individuals who report worries about their employment prospects or who experience involuntary job interruptions are more likely to postpone childbearing. The psychological dimension is important because it captures not only objective contract terms but also how workers interpret their future stability. The combination of objective precariousness and subjective anxiety constitutes a potent deterrent to family formation.

Global Case Studies: How Job Insecurity Shapes Demographic Trajectories

Examining particular national contexts helps to illustrate the multifaceted ways in which job insecurity interacts with culture, policy, and economic structure.

South Korea presents a stark case. Its fertility rate has declined to among the lowest in the world, and debates about causation routinely surface the role of labour market precarity. Young Koreans face intense competition for stable employment with large conglomerates, while a parallel segment of the workforce – frequent temporary and contract workers – remains without the benefits and protections associated with regular employment. The combination of work culture that demands long hours, weak family-supportive policies for precarious workers, and rising housing costs has created an environment in which many postpone or forgo parenthood. Policy efforts that provide financial incentives have had limited success because they fail to address the underlying insecurity that shapes long-term decisions.

Countries in Southern Europe such as Italy and Spain exhibit another pattern in which labour market dualization is pronounced. Youth unemployment rates have remained stubbornly high for decades, and temporary contracts account for a large share of employment among younger cohorts. In Italy, the gradual erosion of protections for permanent employment in certain reform episodes correlated with declines in fertility, particularly among women who perceived higher opportunity costs associated with motherhood. In Spain, the high prevalence of temporary work contributed to delayed family formation, while policy interventions that regularised migrant labour provided a temporary boost to fertility by improving workers’ sense of security.

Japan’s demographic challenges further illustrate the role of employment structure. The persistence of “non-regular” employment – part-time, contract-based, or otherwise precarious – is associated with delayed marriage and childbirth. Cultural expectations about gender roles compound the effect; women who face potential career penalties for childbearing are pushed into a difficult trade-off between maintaining fragile employment and starting families. While Japan has implemented various family-friendly policies, their efficacy is constrained if job security remains elusive for large segments of the population.

The United States exhibits a more mixed but still relevant picture. Despite a larger and more dynamic economy, the rise of gig work, contract labour, and stateside variations in social protections have contributed to differential fertility outcomes. Regions and demographic groups experiencing higher unemployment or lower employment protection tend to record lower birth rates. The COVID-19 pandemic further illustrated how sudden employment shocks can depress fertility, at least in the short run, as households re-evaluate their economic readiness.

Australia provides a contemporary illustration of the interaction between corporate behaviour, job security, and public perception. Reports of large-scale layoffs in major financial institutions, coupled with executive compensation and conspicuous displays of wealth among senior management, have fuelled public resentment. When corporations implement cost-cutting measures that reduce employment stability and simultaneously maintain high executive lifestyles, it produces a narrative of hypocrisy that resonates with the larger argument: actions that undermine job security are inconsistent with the goal of supporting family formation. In such contexts, even if macroeconomic conditions appear stable, symbolic acts and organisational choices can erode trust and reduce the propensity of households to undertake long-term commitments such as childbearing.

Policy Responses: What Works to Rebuild Security and Support Fertility

If job insecurity is a meaningful driver of fertility decline, then public policies aimed at enhancing employment stability and building safety nets should form a crucial part of demographic strategy. A range of policy tools has been deployed across countries with varying degrees of success.

Strengthening employment protections and reducing labour market dualization is one approach. Policies that limit the overuse of short-term contracts, incentivise conversion to permanent employment, and support collective bargaining can increase the share of workers with predictable incomes and protections. Portuguese reforms that converted prolonged temporary employment into permanent contracts are an example of how regulatory change can lead to demographic responses. However, reforms must be carefully designed to avoid unintended side effects, such as excessively rigid labour markets that deter hiring altogether.

Family-friendly workplace policies that make it feasible to combine paid work and childrearing are also crucial. Paid parental leave, when sufficiently generous and shoulderable by employers and the state, has been associated with increased fertility in several contexts. The experience of New Jersey in the United States, where introduction of paid family leave correlated with a discernible rise in births, demonstrates the potential for well-calibrated programs to influence behaviour. Complementary measures – affordable, high-quality childcare; flexible working arrangements; and protections against employment discrimination for caregivers – further reduce the trade-offs that deter parenthood.

Income supports and direct financial policies can also play a role, particularly when they target the economic uncertainty that matters most to families. Child allowances, housing subsidies, and tax credits designed with an eye toward younger families can lower the immediate financial barrier to childbirth. Experiments with unconditional cash transfers and basic income pilots have produced mixed results on fertility, but where they have reduced poverty and smoothed consumption, they have sometimes altered reproductive behaviour by reducing the perceived economic risk of childrearing.

Immigration policy and regularisation efforts can leverage demographic replenishment when integrated workers gain stable access to labour markets and social protections. Spain’s experience with immigrant regularisation underscores how legal status and labour market integration can influence childbearing patterns among migrant populations.

Critically, effective policy packages are holistic rather than piecemeal. Combining employment protections with family policies, active labour market programs that facilitate skill acquisition, and housing affordability measures creates an environment where childbearing is less a leap into the unknown and more a plausible life course. Policies should also be gender-sensitive, recognising that women’s employment prospects and the distribution of caregiving responsibilities shape demographic outcomes. Addressing the “motherhood penalty” through mechanisms such as return-to-work programs and anti-discrimination enforcement helps mitigate the career costs of parenthood that may otherwise suppress fertility.

Public Perceptions: The Lived Experience Behind the Data

Quantitative research tells an important part of the story, but public discourse and lived experience provide texture and urgency. Across social media and public forums, themes recur: the unaffordability of housing, the instability of employment, the difficulty of balancing work and family, and a sense that institutions place a higher priority on shareholder returns than on employee well-being. These narratives reinforce the empirical finding that perceptions of insecurity matter as much as objective conditions.

Anecdotes from online discussions often capture an underlying frustration: people observe layoffs and wage stagnation even while organisations report record profits or executives enjoy substantial compensation packages. Such observations fuel a sense that systemic choices are contributing to the very demographic challenges that public leaders profess to want resolved. This dissonance – between rhetoric about demographic decline and policy or corporate choices that undermine stability – intensifies public cynicism and makes policy interventions that merely papercut around the edges less effective.

There are also intergenerational dimensions to public perception. Young adults who have experienced prolonged entry into stable employment, delayed access to homeownership, and the cumulative effects of precarious early-career episodes are often more sceptical about the feasibility of early family formation. This cohort effect suggests that policy responses need to be adept at altering both immediate conditions and long-term expectations.

Nuance, Trade-offs, and Counterarguments

While the evidence linking job security and fertility is strong, it is essential to acknowledge complexities and potential counterarguments. Fertility decisions are influenced by a constellation of factors including cultural norms, individual preferences, educational attainment, urbanisation, women’s labour force participation, and access to reproductive healthcare. In some contexts, increases in job stability could heighten the opportunity costs of childbearing for women, particularly if stable employment is accompanied by career trajectories that make motherhood particularly costly in terms of lost wages and promotion opportunities. In such cases, policies aimed solely at job security without addressing gendered workplace practices may have limited effect.

Moreover, demographic transitions have long been correlated with structural economic development: as societies urbanize and educational attainment rises, fertility tends to fall. Some scholars therefore argue that long-term fertility decline is an expected outcome of modernisation processes and that labour market insecurity is a proximate, not root, cause. However, empirical studies that control for education, urbanisation, and age structure find that employment insecurity explains variation in fertility beyond what these factors account for.

Another consideration is that immigration can offset population decline in the short to medium term. Yet immigration policies that do not robustly integrate newcomers into secure employment and social protections will not address the underlying forces dissuading native-born residents from having more children. Furthermore, over reliance on migration to sustain population size can create political and social tensions if not managed with transparent, inclusive policies.

Finally, some worry about the fiscal costs and labour market impacts of policies designed to increase job security, particularly in a global economy where firms can shift production and investments internationally. Policymakers must balance the objectives of protecting workers and encouraging demographic renewal with maintaining competitiveness. This tension underscores the importance of carefully designed, evidence-based reforms rather than simplistic or coercive measures.

Conclusion: Stability as a Pillar of Demographic Renewal

The evidence synthesised in this post points to a clear conclusion: job security matters for fertility. It matters not only as an economic variable but as a social condition that shapes expectations, reduces perceived risk, and enables long-term planning. When workers possess stable employment, predictable incomes, and meaningful protections against the vicissitudes of labour markets, they are more likely to view parenthood as feasible. Conversely, when employment is precarious, when entire segments of the workforce confront temporary contracts, volatile hours, and limited benefits, the decision to have children is often deferred or foregone.

Policy responses that aim to address fertility decline must therefore do more than offer cash incentives or public exhortation. They must address the institutional foundations of employment and family life. Strengthening contract protections, reducing labour market dualization, expanding high-quality parental leave and childcare, ensuring access to affordable housing, and implementing gender-sensitive workplace policies together create the conditions under which families can flourish. Equally important is the social narrative: if corporations and elites vocally lament demographic decline while implementing practices that undermine worker stability, public trust erodes and policies lose legitimacy.

Addressing fertility decline through job security is not a panacea, nor is it the sole domain of government. It requires a coordinated approach involving employers, unions, civil society, and policymakers. It requires recognition that demographic health is intimately linked to economic choices and social structures. Ultimately, securing stable, dignified work is not merely an economic imperative; it is an investment in the continuity of communities and the well-being of future generations. If societies value demographic renewal, they will need to restore confidence that young adults can imagine a future with both meaningful work and the possibility of family life. The task is complex, but the stakes – sustaining vibrant, intergenerational societies – are high and immediate.