Introduction

In the heart of Canberra, opposite Old Parliament House, stands a symbol of enduring resistance and hope: the Aboriginal Tent Embassy. Established on January 26, 1972, as a protest against the Australian government’s denial of Indigenous land rights, this site has evolved into the longest-running demonstration for Indigenous sovereignty and self-determination in the world. What began as a simple beach umbrella pitched by four Aboriginal activists – Michael Anderson, Billy Craigie, Bert Williams, and Tony Coorey – has become a beacon for conversations about justice, identity, and coexistence in Australia. My own deep involvement with the Embassy goes beyond mere visits; I actually lived there for a while and represented it in various capacities. This personal immersion has profoundly shaped my understanding of how we discuss Indigenous issues. It revealed not just the deep-seated divisions in our society but also the potential for genuine connection.

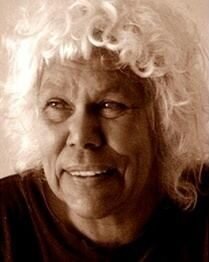

My cousin, Aunty Isobel Coe, was there from the very beginning, playing a pivotal role in its establishment and early days. Her presence and leadership inspired many, including myself, to commit to the cause. Aunty Isobel, a revered Wiradjuri woman born in 1951 at the Erambie Mission near Cowra, New South Wales, dedicated her life to challenging systemic injustices, advocating for land rights, and asserting Indigenous sovereignty. Often referred to as a “mighty warrior” and a “remarkable woman,” her activism spanned decades, influencing key movements and inspiring generations. Her legacy is not merely a record of protests and legal battles but a testament to resilience, community leadership, and the unyielding pursuit of justice for First Nations peoples. Through her involvement in landmark events like the establishment of the Aboriginal Tent Embassy and her high-profile campaigns leading up to the Sydney 2000 Olympics, Aunty Isobel embodied the spirit of resistance against colonial legacies.

During my time living at the Embassy, I encountered a diverse array of individuals, each bringing their own perspectives to the table. These interactions highlighted three distinct archetypes: the fervent allies who embraced the cause with unyielding passion, the overt racists intent on disruption, and the thoughtful middle-ground seekers who approached with curiosity and respect. This tripartite division is not unique to the Embassy; it mirrors broader patterns in Australian discourse on reconciliation. Reconciliation, formally initiated in 1991 as a national process to mend relations between Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples and non-Indigenous Australians, aims to foster mutual respect, address historical injustices, and close gaps in health, education, and opportunity. Yet, as my experiences illustrate, the path to reconciliation is fraught with challenges, often hindered by extremes of enthusiasm or hostility.

At its core, this essay draws from my reflections during my time living at the Embassy, intertwined with the profound legacy of Aunty Isobel Coe, to argue a larger point: true progress in reconciliation requires moving beyond blame and guilt, embracing cultural pride for all, and prioritising practical, respectful dialogue. In a multicultural nation like Australia, where over 300 ancestries coexist and nearly half the population has at least one parent born overseas, fostering understanding is essential. Constant criticism and stereotyping only breed resentment, as seen in the experiences of various communities, including Muslims who face escalating Islamophobia amplified by media and geopolitical tensions. By examining these dynamics through personal anecdotes, historical context, the enduring impact of Aunty Isobel’s work, and broader societal implications, we can envision a more inclusive future. This is not about erasing history but about building bridges where everyone – Indigenous, settler, and migrant – feels invested and respected.

The Embassy itself serves as a microcosm of Australia’s reconciliation journey. Over five decades, it has hosted protests, ceremonies, and dialogues that challenge the status quo. Its persistence underscores the unfinished business of land rights and sovereignty, issues that remain central to Indigenous advocacy. My time living there was eye-opening, revealing how conversations can either widen divides or narrow them. In the sections that follow, I will delve into the three types of people I met, analyse their impacts, explore Aunty Isobel’s life and contributions in depth, and extend the discussion to wider themes of cultural pride and community building, with particular emphasis on the challenges facing Muslim Australians and how my Embassy experiences offer models for inter-community bridges. Ultimately, this reflection is a call to action: stop the hate, reject blanket shame, and start constructing a shared narrative that honours all cultures, much like Aunty Isobel did throughout her life.

The Aboriginal Tent Embassy: A Site of Protest and Dialogue

To fully appreciate the interactions at the Aboriginal Tent Embassy, one must understand its historical and symbolic significance. The Embassy was born out of frustration with the policies of Prime Minister William McMahon’s government, which rejected Indigenous claims to land rights in favour of limited leases. On Australia Day 1972 – a date laden with irony, as it commemorates the arrival of the First Fleet and the beginning of colonisation – the four founders erected their makeshift protest site. This act of defiance quickly grew, attracting supporters and media attention, and has since withstood attempts at removal, including police raids and government decrees.

Aunty Isobel Coe was among the key figures in its founding and ongoing operations, transforming a simple protest site into an enduring symbol of Indigenous sovereignty and land rights. As one of the original activists, she embodied the spirit of resistance that defined those early days. Her leadership not only helped establish the site but also inspired generations, including my own decision to live there and represent it. Aunty Isobel’s work extended beyond the Embassy; she was a tireless advocate for land rights, education, and cultural preservation, often bridging gaps between communities through her wisdom and determination.

The Embassy’s location is no accident; positioned directly across from Parliament House, it serves as a constant reminder to lawmakers of Indigenous sovereignty. It has been a hub for activism on issues ranging from the Stolen Generations – where thousands of Aboriginal children were forcibly removed from their families – to contemporary fights against environmental degradation on sacred lands. In 1995, it was heritage-listed, affirming its cultural importance, yet it remains a living protest, not a museum piece.

My involvement at the Embassy was intimate and sustained. Living there allowed me to immerse myself fully in its daily rhythms, from organising events to engaging with passersby. Aunty Isobel Coe’s foundational role added a personal layer; as a family member and early leader, her stories of the Embassy’s inception fuelled my commitment. What struck me immediately was the diversity of visitors: tourists, students, politicians, and locals, all drawn by curiosity or conviction. These encounters were rarely neutral; they often reflected deeper societal attitudes toward Indigenous peoples. For instance, school groups would arrive with questions about Dreamtime stories, while activists might rally for treaty negotiations. Amid this, the three types of people emerged clearly, each influencing the tenor of discussions.

The fervent allies, often non-Indigenous individuals passionate about social justice, brought energy but sometimes oversimplified complexities. Their presence echoed broader trends in Australian activism, where solidarity movements have grown since the 1967 referendum that granted Indigenous people citizenship rights. However, as I’ll explore, their all-or-nothing approach can alienate potential partners in reconciliation.

In contrast, the racists represented the uglier side of Australian history, rooted in colonial legacies of dispossession and discrimination. From the White Australia Policy to modern-day disparities in incarceration rates – where Indigenous people comprise 3% of the population but 30% of prisoners – these attitudes persist. Engaging with them felt pointless, a drain on resources better directed toward constructive efforts.

Yet, it was the middle-ground individuals who offered the most hope. These were everyday Australians – tradespeople, families, retirees – who approached without agendas, eager to learn. Our conversations often meandered from land rights to shared loves like Australian Rules Football, humanising the exchange. This aligns with reconciliation principles, which emphasize education and relationship-building over confrontation.

The Embassy’s role in facilitating such dialogues cannot be overstated. It has hosted events like the 50th anniversary celebrations in 2022, drawing thousands to reflect on progress and setbacks. Personally, living there and representing the Embassy in discussions and media taught me that reconciliation is not abstract policy but lived interactions. By providing a space for unfiltered exchange, the Embassy challenges us to confront our biases and find common ground. As we move forward, understanding this context is crucial to appreciating why balanced approaches matter in healing national wounds, a lesson deeply influenced by Aunty Isobel’s unwavering advocacy.

The Spectrum of Engagement: Allies, Adversaries, and the Middle Ground

Navigating conversations while living at the Aboriginal Tent Embassy revealed a spectrum of human responses to Indigenous issues, each with distinct motivations and outcomes. This spectrum is emblematic of Australia’s broader reconciliation efforts, where attitudes range from enthusiastic support to outright hostility, with a vital middle space for genuine progress.

First, the eager allies stood out for their passion. These individuals, often from progressive backgrounds, arrived with signs of solidarity – wearing Indigenous-designed clothing or carrying petitions. Their enthusiasm stemmed from a desire to rectify historical wrongs, inspired by movements like the Freedom Rides of the 1960s or the Uluru Statement from the Heart in 2017. However, their zeal frequently led to a binary worldview: Indigenous culture as wholly virtuous, settler society as inherently flawed. This “all-or-nothing” vibe, as I observed, dismissed any positives in non-Indigenous contributions, such as advancements in democracy or technology that have benefited all Australians.

For example, one ally I met argued vehemently that all colonial symbols should be erased, ignoring how shared institutions like the Westminster system have evolved to include Indigenous voices, such as through dedicated agencies. While their hearts were in the right place, this approach erected barriers. It alienated those who might otherwise engage, fostering defensiveness rather than understanding. Research on reconciliation processes suggests that such polarised views can hinder collective healing, as they overlook nuanced histories where Indigenous and settler innovations have intertwined, like in environmental management practices blending traditional knowledge with modern science.

On the opposite end were the outright racists, individuals who appeared not to dialogue but to disrupt. These “chest-beaters,” as I call them, hurled insults like “filth” or “bludgers,” echoing stereotypes rooted in colonial narratives of Indigenous inferiority. Their presence at the Embassy was provocative, often timed to coincide with high-visibility events like Invasion Day protests. Engaging with them proved futile; they were closed to facts, such as the economic contributions of Indigenous businesses or the resilience shown in overcoming policies like assimilation.

Why waste energy on such encounters? History shows that racism thrives on attention, and redirecting focus to education and policy change is more effective. For instance, campaigns aimed at closing health gaps have made strides by prioritising action over confrontation. My experiences reinforced that ignoring these adversaries preserves resources for meaningful work, aligning with reconciliation strategies that emphasise community-led initiatives over reactive debates.

The most impactful group, however, was those in the middle – curious, open-minded individuals who engaged without preconceptions. These folks asked thoughtful questions: “What does sovereignty mean to you?” or “How can I support without overstepping?” Our discussions were balanced; we disagreed amicably on topics like mining on sacred sites, yet parted with respect, often sealing it with a handshake. Later encounters, like sharing a beer at a pub and chatting about cricket, highlighted our shared Australian identity.

This middle ground is where reconciliation flourishes. It embodies the principles of mutual respect outlined in national reconciliation frameworks, which promote narratives that celebrate shared values like mateship and fairness. In multicultural Australia, where diversity is a strength, these interactions remind us that coexistence doesn’t require agreement on everything but a willingness to listen. By nurturing this spectrum’s centre, we can transform potential conflicts into opportunities for growth, paving the way for a more unified society – a vision that Aunty Isobel Coe championed through her lifelong work.

The Pitfalls of Overzealous Allyship

While allies play a crucial role in advancing Indigenous rights, my time living at the Embassy exposed the pitfalls of overzealous support. Enthusiasm, unchecked, can morph into a form of paternalism that undermines the very cause it seeks to champion.

These allies often arrived with preconceived notions, viewing Indigenous struggles through a lens of absolute moral dichotomy. Their rejection of any settler positives – dismissing contributions to infrastructure or arts – created an echo chamber. This mirrors criticisms of “performative allyship” in global social justice movements, where solidarity becomes more about signalling virtue than fostering dialogue.

One interaction stands out: a young activist insisted that all non-Indigenous Australians bear collective guilt for colonisation, ignoring individual contexts. This approach breeds resentment, as studies on guilt in reconciliation show that imposed shame paralyses rather than motivates change. Instead of building bridges, it widens gaps, making non-Indigenous people defensive about their heritage.

Moreover, such allyship can overshadow Indigenous voices. At the Embassy, I saw allies dominating conversations, speaking on behalf of us without invitation. This echoes historical patterns where well-meaning interventions bypassed community input. True allyship requires humility – listening more than leading.

To mitigate these pitfalls, allies should focus on amplification, supporting Indigenous-led initiatives. By doing so, they contribute to sustainable progress without imposing narratives. My reflections underscore that passion must be tempered with nuance to avoid creating barriers in the reconciliation process, a lesson drawn from observing Aunty Isobel’s balanced yet fierce advocacy.

Confronting Racism and Its Futility

Racism at the Embassy was stark and unyielding, manifesting in verbal attacks that sought to demean and provoke. These encounters highlighted why engaging with such bigotry is often a dead end.

The racists I met embodied entrenched prejudices, using slurs that hark back to colonial ideologies justifying dispossession. Their ignorance – claiming Indigenous people “don’t contribute” – ignores facts like the substantial Indigenous economy. Attempting dialogue felt like shouting into the void; they were there to vent, not learn.

This futility is supported by psychological research: deeply held biases resist change without internal motivation. Energy is better spent on anti-racism education in schools or supporting laws against racial discrimination.

The impact on Indigenous communities is profound, contributing to mental health disparities. Yet, resilience shines through, as seen in cultural revivals. By not engaging racists, we reclaim power, focusing on empowerment rather than defence – much like Aunty Isobel did by channelling her energy into constructive activism.

Embracing the Middle: Respectful Conversations and Shared Humanity

The middle-ground individuals at the Embassy offered a refreshing contrast, embodying the potential for authentic reconciliation through respectful engagement.

These people approached with genuine curiosity, free from agendas. Questions were thoughtful, leading to exchanges where we explored differences without heat. For instance, discussing landmark decisions on land rights led to shared insights on justice.

Such conversations build empathy, aligning with reconciliation’s goal of shared understanding. They extend beyond politics; casual chats about sports humanized us, fostering coexistence.

In Australia’s multicultural fabric, this middle ground is vital. It counters polarization, as seen in successful integrations where communities collaborate on festivals or projects. Encouraging more such interactions – through community events or media – can turn listening into action, strengthening national unity.

My experiences affirm that respecting diverse views without guilt trips creates lasting bonds, essential for progress, and echoes Aunty Isobel’s approach to building community alliances.

Moving Beyond Guilt: Fostering Pride and Positives in All Cultures

A key lesson from living at the Embassy is rejecting imposed guilt, instead highlighting positives in all cultures to advance reconciliation.

Pushing blanket shame on settler heritage breeds defensiveness, as I agreed with middle-ground visitors. Psychological studies show guilt can motivate amends, but shame isolates. In Australia, this manifests in backlash against truth-telling efforts.

Instead, celebrate Indigenous resilience – through art and traditions – and settler innovations, like advancements in science and governance. Shared values, such as environmental stewardship, unite us.

This approach aligns with multicultural policies emphasising integration without erasure. By focusing on pride, we reduce resentment, paving the way for collaborative solutions, a principle Aunty Isobel lived by in her advocacy.

Practical Pathways to Reconciliation

Reconciliation demands concrete actions, not just words. Prioritising education, health, and economy ensures all feel invested.

Education reforms, like embedding Indigenous history in curricula, foster understanding from youth. Health initiatives, addressing life expectancy gaps, require culturally sensitive services.

Economic opportunities, via Indigenous enterprises, empower communities. These steps, rooted in respect, turn dialogue into progress.

Encouraging middle-ground conversations amplifies these efforts, creating a ripple effect of positive change, much as Aunty Isobel did through her community leadership.

The Enduring Legacy of Aunty Isobel Coe: Family, Activism, and Inspiration

My cousin Aunty Isobel Coe’s involvement from the Embassy’s inception adds a profound personal dimension to my story. Born into a world marked by segregation and discrimination at the Erambie Aboriginal Mission, a reserve established in the late 19th century for Wiradjuri people displaced by colonisation, she was immersed in traditions that later fuelled her activism. The Wiradjuri nation, one of the largest Indigenous groups in New South Wales, has a rich cultural heritage centred on connection to Country, storytelling, and communal governance. Her family was steeped in advocacy; she was the sister of prominent activists Paul Coe and Jenny Munro, creating a network of support. She married Billy Craigie, one of the Embassy’s co-founders, intertwining her personal life with the struggle.

Aunty Isobel’s activist journey gained momentum in the late 1960s, monitoring police harassment in areas like Redfern, Sydney. This led to the establishment of the Aboriginal Legal Service (ALS) in 1970, the first community-controlled legal aid for Indigenous Australians. At the Embassy, her hands-on involvement included organising demonstrations and ensuring its message resonated globally. Even after its initial phase, she defended its heritage status.

Her commitment extended to the courtroom with the 1993 landmark case Isabel Coe v the Commonwealth, seeking recognition of Wiradjuri sovereignty. Though unsuccessful, it influenced native title claims. As CEO of the Cowra Local Aboriginal Land Council, she focused on housing, education, and economic opportunities, emphasising practical self-determination.

Aunty Isobel gained international prominence before the Sydney 2000 Olympics, criticising the games as “genocide games” and organising protests to highlight disparities. This showcased her media savvy, contributing to Indigenous elements in the ceremony while demanding substantive change.

In later years, she mentored youth, engaged in environmental campaigns, and emphasised healing. As a matriarch, she supported cultural revitalisation. Aunty Isobel passed away on November 10, 2012, at 61, prompting widespread tributes. Her legacy endures in the Embassy’s persistence, legal advancements, and educational inclusion. She inspired new activists, and her family carries forward the fight. In media and arts, her story counters erasures, reminding us that reconciliation requires sovereignty and equity.

Living at the Embassy allowed me to carry forward that legacy. Representation meant speaking at events and educating visitors, drawing on Aunty’s stories to humanise the struggle. This familial connection highlights that reconciliation benefits from personal narratives, promoting pride across cultures.

Challenges in Sustaining the Embassy’s Message

Living at the Embassy also exposed me to the challenges of sustaining its message amid evolving societal dynamics. Over time, the site has faced threats from development pressures and political shifts, requiring constant vigilance. My representation involved advocating for its protection, reminding authorities of its heritage status and cultural significance – efforts that echo Aunty Isobel’s defensive strategies.

These challenges mirror national issues, like debates over constitutional recognition. The failed Voice referendum in 2023 underscored divisions, yet it also sparked renewed conversations. From my vantage at the Embassy, I saw how middle-ground engagements could heal such rifts, turning disappointment into determination, in line with Aunty Isobel’s resilient approach.

Sustaining the message means adapting without compromising core principles. By focusing on positives – like collaborative projects blending Indigenous knowledge with modern solutions – we can keep the dialogue alive, honouring Aunty Isobel’s vision.

Education as a Cornerstone of Change

Education emerged as a key theme during my time at the Embassy. Many visitors, especially from the middle group, sought knowledge about Indigenous history, prompting discussions that bridged gaps – a practice Aunty Isobel championed through mentorship.

Formal education plays a vital role; integrating Aboriginal perspectives into school curricula helps dismantle stereotypes from an early age. My interactions reinforced this: when people learned about the Embassy’s origins, including Aunty Isobel’s role, their views often softened.

Beyond schools, community education through workshops and media is essential. Representing the Embassy meant facilitating these, turning curiosity into allyship without the pitfalls of overzealousness, much like Aunty Isobel’s educational initiatives.

Health and Well-Being: Addressing Inequities

Health disparities were another focal point. Indigenous Australians face higher rates of chronic diseases, influenced by historical traumas. At the Embassy, conversations often touched on this, with middle-ground visitors expressing genuine concern – issues Aunty Isobel highlighted in her advocacy.

Practical steps include culturally appropriate health services and community-led programs. My experiences showed that respectful dialogue can lead to support for these initiatives, fostering investment from all sides, aligning with Aunty Isobel’s community-focused efforts.

Economic Empowerment and Self-Determination

Economic opportunities are crucial for reconciliation. Living at the Embassy highlighted how land rights tie into prosperity. Discussions with visitors revealed misconceptions about Indigenous economies, which I countered with examples of thriving businesses – areas where Aunty Isobel made significant impacts through land councils.

Empowerment through self-determination – via treaties or economic partnerships – builds pride and reduces dependency. This aligns with my call to celebrate positives, creating a cycle of mutual benefit, as demonstrated by Aunty Isobel’s work in Cowra.

Multicultural Parallels: Lessons from Muslim Communities and Building Inter-Community Bridges

Extending the Embassy’s lessons to other marginalised groups in multicultural Australia reveals striking parallels, particularly with Muslim Australians who confront pervasive Islamophobia rooted in historical prejudices and amplified by contemporary events. Islamophobia in Australia, characterised by distrust, hostility, and bias towards Muslims and Islam, has deep historical roots that predate modern global events, evolving from colonial-era policies to contemporary surges tied to international conflicts and domestic politics. This phenomenon has marginalised Muslim communities, leading to discrimination, violence, and social exclusion, while also prompting responses aimed at fostering understanding and legal protections.

The seeds of Islamophobia in Australia were sown during the colonial period, intertwined with the nation’s immigration policies and racial hierarchies. Muslims first arrived in Australia as early as the 17th century through Makassan traders from Indonesia, who engaged in trepang (sea cucumber) harvesting with Indigenous communities in northern Australia. However, systematic bias emerged with the influx of Afghan cameleers in the 1860s–1920s, who played a vital role in exploring and developing the Australian interior but faced discrimination as “non-white” outsiders. The White Australia Policy (1901–1975), a cornerstone of early federation, explicitly restricted non-European immigration, including Muslims, reinforcing a narrative of cultural incompatibility and viewing Islam as alien to the predominantly Anglo-Christian society. This policy not only limited Muslim settlement but also embedded fears of the “other,” portraying non-Western cultures as threats to national identity.

By the late 20th century, as multiculturalism gained traction post-1970s, Islamophobia manifested in more targeted ways. During the First Gulf War (1990–1991), anti-Arab and anti-Muslim sentiments escalated, with media and political rhetoric framing Middle Eastern conflicts as direct threats. This period saw a wave of racist attacks, including vandalism of Arab-owned businesses, bomb threats to Islamic institutions, and harassment of individuals with Muslim-sounding names like “Hussein.” The Australian Security Intelligence Organisation (ASIO) conducted surveillance and wiretaps on Muslim communities, stigmatizing them as potential security risks, even though no domestic attacks materialized. These actions, amplified by sensationalist media, laid the groundwork for viewing Muslims through a lens of suspicion, a pattern that would intensify in the following decades.

The September 11, 2001, terrorist attacks in the United States marked a pivotal turning point, catapulting Islamophobia into mainstream Australian discourse. Prejudices that had simmered now boiled over, with Muslims constructed as the “other” in public narratives to reaffirm Western values and national security. Politicians and media outlets often stereotyped Muslims as violent or misogynistic, associating Islam with terrorism and oppression. Surveys from this era reflect the shift: a 2011 poll found 48.6% of Australians held negative views of Islam, while a 2014 study revealed 25% harboured anti-Muslim sentiments – five times higher than for other religions – and 27% of Muslims reported experiencing discrimination, the highest rate among faith groups.

Contributing factors included heightened counter-terrorism measures, such as the 2005 Anti-Terrorism Act, which disproportionately affected Muslim communities through raids and profiling. The 2005 Cronulla riots exemplified this tension: sparked by perceived clashes between Lebanese-Australian (often Muslim) youth and local surfers, the riots involved mobs chanting anti-Muslim slogans, attacking individuals of Middle Eastern appearance, and desecrating mosques. Media coverage sensationalised these events, portraying Muslim migrants as failing to integrate, further entrenching biases. This decade also saw the rise of far-right groups exploiting these fears, normalising Islamophobic rhetoric in public debates on multiculturalism.

The 2010s witnessed a surge in organized Islamophobia, fuelled by global events like the rise of ISIS and domestic political opportunism. Anti-halal certification campaigns in 2014, led by groups like the Q Society, claimed that halal labelling funded terrorism and imposed Islamic practices on Australians, leading to boycotts and economic pressure on companies. This resulted in businesses like Fleurieu Milk & Yoghurt dropping halal products amid threats, highlighting how economic discrimination targeted Muslim practices.

Protests became a hallmark of this period. The 2014–2015 Bendigo mosque controversy saw far-right groups, including the United Patriots Front (UPF), rally against a proposed mosque, distributing hate literature and mobilising thousands, often with neo-Nazi involvement. Similarly, Reclaim Australia rallies from 2015 onward framed Islam as a threat to Australian values, with speakers vilifying Muslims and encouraging contempt. A 2015 UPF protest in Bendigo involved beheading a mannequin to symbolise anti-Muslim violence, leading to 2017 convictions under Victoria’s Racial and Religious Tolerance Act.

Media and political figures amplified these sentiments. In 2016, an Australia Day billboard featuring Muslim girls in hijabs was removed due to abuse and threats. The 2017 Q Society fundraiser featured derogatory speeches, attended by politicians like Cory Bernardi. By 2016, surveys showed 10% of Australians held hostile attitudes towards Muslims, more prevalent among older, less-educated demographics. The 2014 Martin Place siege, though not ideologically motivated, was exploited to justify increased surveillance.

The decade culminated in the 2019 Christchurch mosque shootings in New Zealand, perpetrated by an Australian white nationalist, killing 51 Muslims. This tragedy exposed the transnational nature of Islamophobia, with Australian Senator Fraser Anning blaming Muslim immigration, drawing global condemnation. In the 2019 federal election, several parties incorporated anti-Muslim policies, underscoring how Islamophobia had infiltrated mainstream politics.

The COVID-19 pandemic and geopolitical tensions have exacerbated Islamophobia. Lockdowns amplified online hate, while the 2023 Israel-Hamas conflict triggered a dramatic spike: the Islamophobia Register Australia recorded a 13-fold increase in incidents from October to December 2023, including verbal abuse, physical assaults, mosque threats, and doxing. By early 2025, research suggested incidents had doubled over the previous two years, with 309 in-person cases between 2023 and 2024, disproportionately affecting women and girls in hijabs.

Far-right groups have normalized Islamophobia in “respectable” discourse, with media stereotyping persisting despite some positive coverage. Impacts include mental health strains, under-reporting of hate crimes, and barriers to employment and education. Muslim women, often visible through hijabs, bear the brunt, facing harassment while navigating public spaces.

Throughout history, Islamophobia has led to profound marginalisation: higher discrimination rates (27% in 2014), economic boycotts, hate crimes, and social exclusion. Responses include grassroots campaigns like #IllRideWithYou (2014), offering solidarity post-siege, and the 2015 Voices against Bigotry network. Legislation such as the Racial Discrimination Act 1975 provides protections, but critics note gaps in enforcement. In 2024, the government appointed envoys for Islamophobia and anti-Semitism, and a 2025 report by envoy Aftab Malik proposed 54 recommendations, including hate crime data improvements and parliamentary codes.

In summary, Islamophobia in Australia has evolved from colonial exclusion to a multifaceted issue driven by global events, media, and politics. While progress through advocacy exists, recent surges highlight the need for continued efforts to combat bias and promote inclusion.

Yet, my experiences at the Aboriginal Tent Embassy offer a powerful model for building inter-community bridges to counter these issues. The Embassy’s emphasis on middle-ground dialogues – where diverse visitors engaged respectfully without preconceptions – demonstrates how shared spaces can foster empathy and dismantle stereotypes. Just as I connected with non-Indigenous Australians over common interests like sports, leading to mutual respect, similar interactions could unite Indigenous and Muslim communities. For instance, collaborative events at the Embassy or similar sites could highlight shared histories of marginalization: both groups have endured colonial dispossession, systemic racism, and over-policing, with Indigenous incarceration rates mirroring the disproportionate scrutiny Muslims face under security laws.

Drawing from Aunty Isobel’s legacy of bridging gaps through wisdom and determination, initiatives like joint workshops on cultural pride could empower both communities. Imagine Indigenous elders sharing Dreamtime stories alongside Muslim leaders discussing Islamic principles of justice and hospitality – conversations that humanize differences and reveal common values like respect for the land and community cohesion. My time representing the Embassy taught me that rejecting blanket guilt and focusing on positives, such as the resilience of Muslim contributions to arts, medicine, and business, can reduce resentment and build alliances. In practical terms, this could involve interfaith Sabbath meals or multicultural festivals where stories are exchanged, mirroring the unity I’ve witnessed in diverse gatherings.

By applying the Embassy’s lessons – prioritising listening over lecturing and action over abstraction – we can address Islamophobia head-on. Community-led programs, supported by policies that fund anti-discrimination education and promote media accountability, would amplify these bridges. Ultimately, these efforts not only support Muslim Australians but strengthen Australia’s social fabric, turning potential divisions into sources of collective strength.

Media’s Role in Shaping Narratives

Media influences perceptions profoundly. During my time at the Embassy, coverage varied from supportive to sensationalist. Representing it involved correcting misrepresentations, emphasising nuance – a skill Aunty Isobel mastered in her Olympic campaigns.

Responsible media can amplify positive stories, reducing hate. By highlighting shared humanity, it supports reconciliation across cultures, continuing Aunty Isobel’s media advocacy, especially in countering narratives that fuel Islamophobia.

Community Building Through Shared Activities

Shared activities foster bonds. At the Embassy, casual talks about sports bridged divides. Extending this, community events – like multicultural festivals – build understanding, embodying Aunty Isobel’s unity-building ethos and offering platforms to address Muslim Australians’ challenges through inclusive participation.

These grassroots efforts complement policy, turning abstract reconciliation into tangible connections.

Policy Recommendations for Progress

To advance, policies must prioritize respect. Recommendations include strengthening anti-discrimination laws, funding Indigenous-led programs, and promoting cultural education – reforms Aunty Isobel fought for. Specifically for Muslim communities, enhancing hate crime reporting and integrating multifaith sensitivity training in policing would mitigate systemic biases.

Involving all stakeholders ensures buy-in, avoiding resentment.

Personal Growth from the Experience

Living at the Embassy transformed me. It taught patience, the value of listening, and the power of pride. Aunty Isobel’s legacy guided this growth, reinforcing that change starts with individuals and extends to bridging divides with groups like Muslim Australians.

Future Visions: A United Australia

Envision an Australia where cultural pride unites us. By rejecting hate and embracing dialogue, we can achieve this. The Embassy’s enduring spirit, fuelled by figures like Aunty Isobel, points the way toward a society where Indigenous and Muslim communities collaborate to overcome shared adversities.

Conclusion

Reflecting on living at the Aboriginal Tent Embassy and the profound legacy of Aunty Isobel Coe, it’s clear that reconciliation thrives on balanced, respectful dialogue. By rejecting extremes, embracing cultural pride, and pursuing practical steps, we can bridge divides. For Indigenous, Muslim, and all Australians, it’s time to build community over criticism – imagining a future where understanding prevails, honouring Aunty Isobel’s unyielding spirit.