Introduction

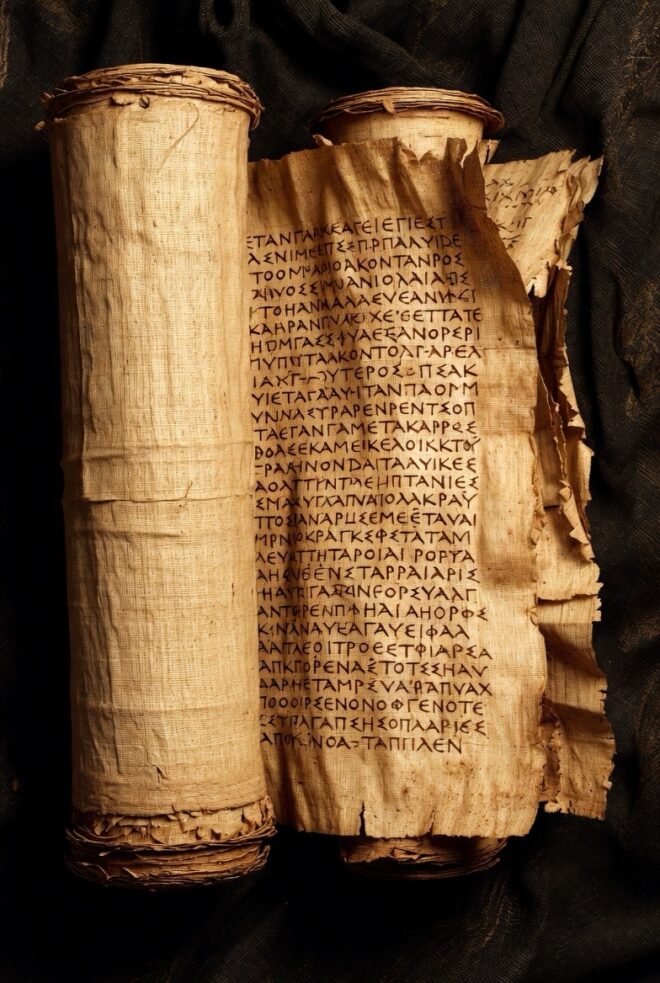

Herodotus of Halicarnassus has been the subject of alternating admiration and scepticism for nearly two and a half millennia. Lauded as the “Father of History” for assembling an unprecedented chronicle of the Greek world and its neighbours, he has also been charged with credulity, dependence on hearsay, and occasional inaccuracies. Nowhere do these debates concentrate more fruitfully than in his references to Palaistinê – rendered in English as “Palestine” – and to the peoples associated with that name, particularly the Philistines. The surviving passages in The Histories that use the term Palaistinê are few but consequential. They provide one of the earliest extant Greek testimonies to a geographical designation that would have an extraordinary afterlife in classical and later political vocabularies.

This essay argues that, read sympathetically and contextually, Herodotus’ treatment of Palaistinê and of the region’s inhabitants deserves greater respect than is often accorded. Rather than dismissing his work as a repository of odd tales, we should acknowledge Herodotus as a careful inquirer working within the constraints and conventions of fifth?century BCE historiography and ethnography. His method – compiling oral reports, questioning informants, comparing rival accounts, and situating local traditions within larger politico?geographic frameworks – yields a textured and reliable snapshot of how the Eastern Mediterranean and its coastal districts were perceived in an era dominated by the Achaemenid Empire. When it comes to Palestine, Herodotus both preserves traces of local memory and articulates an administrative reality that corresponds with Persian imperial organization. In matters of origin and cultural diffusion, his willingness to record multiple traditions, even when they conflict, is not a weakness but an expression of scholarly prudence.

Below, I offer a systematic and sympathetic reading of Herodotus’ references to Palaistinê, defending his approach to ethnography and showing how his account can be reconciled with – and indeed enriches – modern archaeological and historical perspectives on the Philistines and the coastal Levant.

Herodotus’ Method: A Reappraisal

To evaluate Herodotus fairly, one must begin with his own self?presentation. He explicitly frames The Histories as an inquiry (historí?) into the causes and consequences of the Greco?Persian conflicts, but he does not restrict himself to political narrative. He views human actions, customs, and migrations as part of a network of causes and consequences that require careful collation of testimony. This epistemic humility – collecting accounts, noting divergences, and occasionally stating preference for one report over another – distinguishes him from later, dogmatic chronologies.

Critics often cite Herodotus’ reliance on oral tradition as an epistemic liability. Yet the reliance on oral testimony was the principal avenue for knowledge about many distant polities in the fifth century BCE. In this light, Herodotus’ practice of recording multiple versions of events and explicitly attributing claims to named peoples or locales demonstrates an early form of source criticism. Rather than presenting a single authoritative narrative, he annotates where his accounts are derived from sailors, Persian officials, Egyptian priests, or local informants. This transparency allows later readers to assess plausibility and cross?reference other materials.

Importantly, Herodotus was a traveller. The coastal circuits of the eastern Mediterranean – Phoenician harbours, Cypriot ports, Egyptian ports, and the coastal cities of the southern Levant – were well within the travel horizons of seafaring Greeks and Persian administrators. The vantage point of a traveller is necessarily maritime and urban, and the resulting emphasis in The Histories on coastal polities and seafaring peoples is therefore both natural and informative. When Herodotus describes Palaistinê as a coastal district, he is reflecting the lived geography of the ancient Mediterranean – not merely perpetuating stereotypes, but recording the operational reality that the sea, more than inland hills, structured trade, networks, and imperial administration.

Finally, we should recognise Herodotus’ comparative method. He often explains local customs by situating them in a web of borrowings and contacts – Egyptian influence in the Levant, Greek parallels to barbarian customs, or Persian administrative practice adapted to provincial particularities. This comparative stance is precisely what scholars employ today when interpreting material culture and textual traces in light of cross?cultural interaction. Herodotus therefore anticipates, in rudimentary form, many principles of later historical and anthropological inquiry.

Palaistinê in Herodotus: Geographical Precision and Administrative Awareness

Herodotus uses the name Palaistinê seven times, and in each occurrence the term functions as a geographical marker, usually associated with the seaboard that stretches between Phoenicia and Egypt. Interpreted with attention to the historical and administrative realities of the Achaemenid Empire, Herodotus’ usage is strikingly precise.

First, his portrayal of the coastal strip as a distinctive district corresponds with external evidence that the Persians organised the Levantine littoral into administrative units that privileged maritime communications and revenue extraction. When Herodotus lists the satrapal contributions or the naval contingents furnished by “the Phoenicians with the Syrians of Palestine,” he is doing what any careful inquirer would do: translating local administrative practice into units intelligible to his Greek readership. The fact that he identifies the contribution of ships from these coastal peoples suggests that he understands both the economic specialisation of the coast and the political protocols by which subject peoples were levied.

Second, Herodotus consistently emphasises the environmental character of this coastal district: sandy soil, limited freshwater, and a mode of living oriented toward the sea. Such descriptions may seem stereotypical if read superficially. In context, however, they capture an important ecological distinction: the dearth of arable hinterland in much of the Philistine pentapolis and adjacent littoral shaped the economies and strategies of urban centres in ways that differed from the upland Judean and Galilean highlands. Herodotus’ focus on seafaring capacities and urban port life, therefore, is not a casual omission of inland realities but a careful observation of what made Palaistinê functionally distinct within the larger Syrian matrix.

Third, his occasional identification of specific cities – Askalon (Ashkelon), Gaza (Cadytis), and other coastal locales – provides a concrete reminder that he is not speaking in abstract generalities. The inclusion of episodes such as the Scythian incursion to Askalon, or of Gaza as a waypoint en route to Egypt, anchors his geography in events and practices that resonate with archaeological finds: fortified coastal settlements, maritime trade networks, and the strategic importance of littoral gateways.

Rather than treating Palaistinê as an ambiguous or pejorative label, Herodotus uses it as a functional geographic term. He captures a coastal district that, for the Persian imperial apparatus and for seaborne travellers, constituted a coherent region. In this respect he preserves an administrative and perceptual reality that later historians and geographers would refine but not fundamentally contradict.

Herodotus and Philistine Origins: Preserving Local Memory

The question of Philistine origins has long animated scholarship. Archaeology has illuminated a great deal: Aegean?style pottery, architectural motifs, and certain onomastic traces indicate contacts – or migrations – from the wider Mediterranean in the late Bronze Age and the tumultuous era of the so?called Sea Peoples. Yet these material signals do not fully exhaust the variety of memories preserved in the Levant and neighbouring lands. Here Herodotus’ testimony, properly weighed, contributes an additional strand of tradition.

Herodotus records, or at least reproduces, narratives that associate the inhabitants of the Syrian coast with movements from the east – stories of peoples crossing the Erythraean waters or claiming origins by the Red Sea. At first glance this seems to contradict the Aegean link. A dismissive reading would label Herodotus as confused. A more charitable and productive reading, however, recognizes two vital points.

First, ethnogenesis rarely follows a single, unidirectional path. The formation of coastal polities in the late Bronze and early Iron Ages likely involved multiple migratory pulses, maritime contingents, mercenary settlements, refugee movements, and assimilation of pre?existing populations. The Philistine identity that emerges in the material record at sites like Ashkelon, Ashdod, Ekron, and Gath may well be a composite – Aegean seafarers interacting with Canaanite hinterland communities and with other Mediterranean and Near Eastern groups. Memories of diverse origins – Aegean, Anatolian, Cypriot, and perhaps even Red Sea connections via mercantile networks – could coexist in local narratives. Herodotus’ record of eastern origin stories therefore preserves a strand of local memory rather than fabricating it.

Second, Herodotus’ habit of recording local claims – “as they themselves say” – is a methodological virtue. He does not assert as fact what he has only heard; instead he passes along the traditions of the peoples he encountered or whose accounts reached his informants. When he transmits a Red Sea origin for coastal peoples, he is faithfully conserving a version of how those coastal communities or their neighbours understood their own history. Modern archaeology cannot, and should not, discount every oral tradition out of hand. Instead, it can treat such traditions as data: testimonies that may echo lost migrations, economic ties, or mythic reworkings of historical experiences.

It is also worth appreciating that Herodotus’ grouping of “Phoenicians” and the “Syrians of Palestine” in certain contexts reflects an outsider’s attempt to delineate cultural and economic solidarities. To Greek ears, maritime peoples shared certain social and commercial features, and Herodotus rightly perceives a maritime sphere of influence stretching from Anatolia down to Egypt’s northeastern shores. This perception accommodates both the Aegean elements traceable in ceramic repertoires and the eastern contacts visible in trade goods and shared customs. Herodotus’ synthesis is therefore not contradictory but pluralistic: he records one tradition of origin without excluding others, leaving later readers to integrate archaeological data and textual evidence into a fuller narrative.

Herodotus and Cultural Diffusion: Explaining Customs Without Denigration

A recurrent element in Herodotus’ treatment of Levantine peoples is his attention to cultural practices – circumcision, modes of burial, dietary habits – and his effort to explain them by appeal to contact and diffusion. Critics sometimes interpret this as a simplistic diffusionism. On the contrary, Herodotus’ approach embodies an empirical sensitivity: he looks for proximate causes and mechanisms – trade, conquest, priestly transmission – by which customs travel across regions.

When he suggests, for instance, that circumcision in certain Syrian communities derives from Egyptian influence, he is articulating a plausible diffusionary pathway. The Nile Valley was a major cultural crucible whose religious and hygienic practices were widely known and admired throughout the eastern Mediterranean. Merchants, soldiers, and priests were potent vectors of custom. Herodotus is not claiming a universal and exclusive Egyptian origin for every Levantine practice; rather, he is identifying a significant line of influence that fits the political and economic structures of the era.

This attention to cultural transmission is valuable because it helps modern readers recognise the Levant as a contact zone. Herodotus’ ethnographic snapshots underscore fluidity, not fixity. He presents communities as adaptive, borrowing and transforming practices in response to trade ties, imperial policies, and environmental conditions. Such a portrayal resists essentialist readings that reduce ancient groups to timeless ethnic types. Far from being anachronistic, Herodotus’ sensibility resonates strongly with current scholarly models that emphasise hybridity, entanglement, and the continual reconfiguration of identities in response to cross?cultural contact.

Herodotus and Later Reception: Naming, Memory, and Imperial Politics

Herodotus’ use of the name Palaistinê has profound consequences for the subsequent history of the region’s nomenclature. By recording a Greek form of the name that likely derives from Semitic Peleshet or Assyrian Pilistu, Herodotus participates in the translingual circulation of toponyms. His work helped stabilise a Greek lexical form that would persist in Hellenistic and Roman writings and ultimately underpin later administrative and literary usages of “Palestine.”

It is crucial, however, to distinguish the descriptive function that Herodotus gives the term from the later politicised renaming carried out by Roman authorities. Herodotus is not engaging in an act of imperial erasure; he is describing a coastal district that, in the Persian imperial frame, was recognised as a unit of maritime economy and urban settlement. When, two centuries after Herodotus, Greek and Roman geographers and, still later, imperial administrators deploy the same root name in broader or different senses, they are participating in a long process of semantic expansion, which is not attributable to Herodotus’ intentions.

Moreover, Herodotus’ work contributes an essential baseline for those seeking to understand how regional names acquire layered meanings over time. His Palaistinê provides evidence of a fifth?century BCE usage that links the name to a coastal identity and to the memory of Philistine presence, thereby anchoring later discursive shifts to a documented precedent. In this respect, Herodotus’ contribution is not marginal but foundational.

Reconciling Herodotus with Archaeology and Genetics: Complementarity, Not Contradiction

One might summarise the most constructive contemporary approach to Herodotus thus: his narratives are best treated as complementary to material evidence. Archaeological discoveries – Mycenaeanizing pottery in Philistine strata, architectural innovations, dietary and isotopic studies, and, more recently, ancient DNA analysis – provide solid data about population movements, cultural practices, and biological ancestry. Herodotus adds the indispensable human dimension of memory and self?representation. He tells us how people in or near the region, or those who had travelled there, recounted their pasts and made sense of their place in a network of empires and seas.

Where archaeological data indicate Aegean affinities in the material culture of early Philistine settlements, Herodotus’ eastern origin narrative can be read alongside rather than against such evidence. It is conceivable, for instance, that some maritime groups with eastern roots later absorbed Aegean elements through trade or subsequent migration. Alternately, eastern origin legends might memorialise a different phase of population movement – perhaps the arrival of mercantile contingents, sailors, or political elites from the Red Sea or Arabian littoral – whose material footprint would be subtle relative to that of bulk settler communities. We should avoid the false dichotomy that pits textual testimony against archaeological fact; instead, we should integrate them into a layered, diachronic account of the region’s complex ethnogenesis.

Conclusion

Herodotus remains an indispensable witness to the ancient Mediterranean precisely because he recorded both what people did and what they said about themselves. His references to Palaistinê and to the coastal peoples of the southern Levant are not idle curiosities but deliberate contributions to a larger inquiry into the working of empires, the flow of peoples, and the diffusion of customs. When read on their own terms – attentive to his method, his sources, and his maritime vantage – Herodotus’ accounts display a measured empiricism and a pluralistic sensibility that anticipate modern historiographical practice.

To reduce Herodotus to a teller of fables is to miss the rigour of his curiosity and the value of his ethnographic attentiveness. His work preserves traditions and administrative perceptions that complement archaeological and genetic discoveries. It provides, moreover, a terminological anchor for the later history of a name – Palaistinê – that would resonate across centuries.

For contemporary readers and students of the ancient Levant, the lesson is clear: Herodotus should be treated not as a final authority but as a conscientious informer whose testimony, carefully weighed and integrated with material evidence, yields a richer and more complex account of the coastal Levant and the people whose memory lives on in the name Palestine.