Ngaya bamal.

Sun rides high – warami, old people,

the barray (land) shimmers

as cicadas cry out their heat song.

By the ngurra (camp),

we weave,

fish for garara (mullet),

burra (children) run beside the gum,

cool in the shade –

warami, barray, as always.

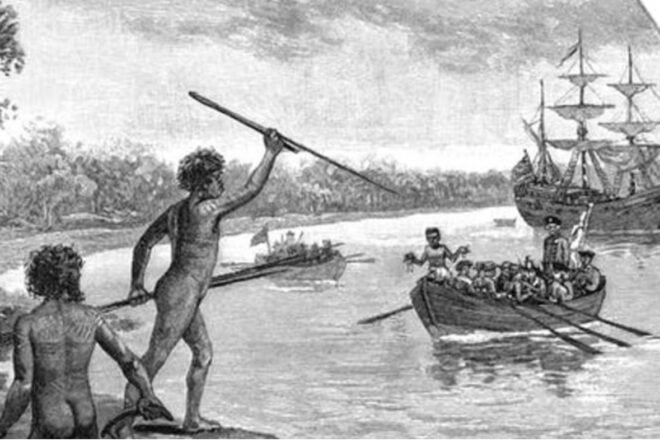

Then the sea grows restless.

Shapes on the ngura (water)

big and sharp, white as yamay (clouds),

not whale, not canoe,

not remembered by river or Sky Father.

We crouch behind rocks,

old people holding burra close,

our hearts jumping like garradja (kangaroo).

White-faced men

in heavy, shining ngurunga (clothing),

not possum skin nor wallaby –

wrapping their skin in strangeness,

walking as if they own barray,

loud voices crashing.

Doongal (confusion) swirls;

are they ghosts from old story?

Garrigarang (sea) and ngurra (earth) do not welcome,

the air is tight with never-before.

We keep to shadow,

speak low –

Ngaya bamal? Who are these ones?

Why no song, no ochre on skin,

no word to Country before they drink,

no gift to the spirits?

Do they know guray (law)?

Do they see buluwang (important places)?

They point,

they gather wood selfishly,

no glance for Daramu (trees),

no sign for Biyal (sky).

Fish sense strangeness –

garara hide deep,

birds watch, silent on high branches.

Even the wind,

nhamarra (friend), is unsure.

We take the story home,

speak to winangadyi (elders),

words like dhiyara (ashes):

Ghosts? Lost? Trouble?

Our tongues twist around new threats.

We sit around the fire,

eyes wide in the orange burn –

the dreaming feels thinned,

even the night creaks different.

But mother holds burra close,

old ones sing soft into darkness –

telling Country we remember,

telling ancestors we watch.

Ngaya Gadigal.

We belong to Warrane.

No storm, no strangeness

can break our song,

carrying us forward

as stars paddle the night.

by Bakchos