Undefeated

He kneels, yet will not bow his head –

Night gathers round, the field is lost,

But from his wounds and earth-stained skin

Still blazes pride, undimmed by cost.

His sword lies broken at his side,

Fragments glinting in failing day,

Yet in his grasp remains the will

To meet his fate, to face, not sway.

He does not plead for gentle night

Nor curse the foe that pressed him low;

His gaze burns out against the dark

With all the fire he used to show.

Defiance steels his lifted face –

Though nation, love, and comrades fall,

He stands for all who choose to fight

And perish, but will not crawl.

Let victors strut and songbirds hush –

They cannot claim what he defends:

A soul unbowed, a final breath

That, fierce, will not break or bend.

The sword is broken – he is not;

Within his silence thunder rings:

“You took my life, but not my thought –

A free man dies, a free man sings.

Bakchos

Introduction

The history of Australia is a complex tapestry woven with threads of exploration, settlement, and profound conflict. At its core lies the story of Indigenous dispossession and resistance, often obscured by triumphant narratives of pioneering. The Wallabadah Manuscript, a firsthand account penned by Scottish immigrant William Telfer in the late 19th century, pierces this veil with unflinching detail. Telfer’s recollections capture the brutal frontier wars of the 1830s in northern New South Wales, centring on a poignant quote: “… In that year the Aborigines were subjugated after a stubborn resistance and never rose against the white man to fight again dying out altogether leaving the whites in possession of their Country for Ever more.” This statement, tied to the events of 1838, including the massacre of up to 200 Aboriginal people at Slaughterhouse Creek, encapsulates the colonial mindset that viewed Indigenous Australians as impediments to progress, destined for extinction.

Yet, this narrative of inevitable disappearance is a myth, one challenged by the remarkable resilience of Aboriginal nations such as the Gamilaraay and Wiradjuri. The Gamilaraay, whose lands encompass the sites of these massacres, and the neighbouring Wiradjuri, have not only survived but revitalised their cultures, languages, and connections to Country. This essay merges historical analysis of colonial violence through the lens of the Wallabadah Manuscript with explorations of Gamilaraay and Wiradjuri resilience, forming a cohesive examination of subjugation, survival, and revival. It argues that while colonial atrocities sought to erase Indigenous presence, the enduring strength of these peoples – manifest in language reclamation, cultural practices, and advocacy – affirms their sovereignty and contributes to national reconciliation.

To fully appreciate this interplay, we must first delve into the manuscript’s authorship and content, then examine the specific events it describes, explore broader patterns of frontier violence, and finally highlight the multifaceted resilience of the Gamilaraay and Wiradjuri. By expanding on these elements, we uncover how historical documents like Telfer’s, while products of their time, serve as catalysts for truth-telling in contemporary Australia. The manuscript not only documents the brutality but inadvertently underscores the failure of colonial efforts to fully extinguish Indigenous spirit. As we proceed, we will see how the Gamilaraay and Wiradjuri have drawn upon ancient knowledge systems to navigate modern challenges, turning sites of trauma into spaces of healing and empowerment.

Historical Context: Frontier Wars and the Wallabadah Manuscript

To grasp the significance of the Wallabadah Manuscript, one must contextualise it within British colonisation’s broader framework. The First Fleet’s arrival in 1788 initiated what historian Henry Reynolds calls the “Australian frontier wars,” conflicts that claimed tens of thousands of Indigenous lives over a century. These wars were not formalised battles but a series of skirmishes, ambushes, and massacres driven by the insatiable demand for land. In New South Wales, expansion surged in the 1820s and 1830s, with squatters venturing beyond Sydney into the fertile Liverpool Plains, Namoi, and Gwydir River valleys. These regions, home to the Gamilaraay and adjacent Wiradjuri nations, were prized for pastoral pursuits supporting Britain’s wool economy. The Liverpool Plains, in particular, were described by early explorers as a “paradise” of black soil ideal for grazing, but this paradise was already inhabited and managed by Indigenous peoples for millennia.

The doctrine of terra nullius declared Australia uninhabited, denying Indigenous land rights and enabling unchecked seizure. Chief Justice Richard Bourke’s 1835 proclamation reinforced this, allowing squatters to occupy vast areas without recompense. However, Aboriginal groups resisted. The Gamilaraay, with a pre-colonial population estimated at 15,000, and the Wiradjuri, numbering over 12,000, possessed intricate societies: kinship systems, spiritual ties to Country, and sustainable practices like mosaic burning to promote biodiversity and game abundance. Their economies were based on seasonal movements, hunting kangaroos and emus, gathering yams and seeds, and fishing in rivers teeming with life. Spiritual beliefs centred on creators like Baiame, who instilled laws of reciprocity with the land.

Initial settler interactions were pragmatic – Aboriginal guides aided navigation, stripped bark for huts, and shared knowledge of water sources – but escalated into violence as livestock disrupted food sources and stockmen interfered with women. Aboriginal responses included spearing cattle as a form of economic warfare and targeted attacks on isolated settlers. Colonists framed these as unprovoked aggressions, ignoring the invasion’s root cause. By the mid-1830s, the frontier resembled an undeclared war, with reports of “depredations” filling colonial newspapers.

Governor George Gipps, arriving in 1838, promoted protection influenced by British humanitarians, but settlers often ignored this, forming vigilante groups. The Myall Creek massacre in June 1838, where 28 Wirrayaraay (a Gamilaraay subgroup) were killed, led to rare prosecutions – seven men hanged – but most atrocities escaped justice, as juries sympathized with perpetrators. The year 1838 marked a violent peak, with Major James Nunn’s January expedition culminating in the Waterloo Creek massacre of 40-70 Gamilaraay. This sparked “The Bushwhack,” an extermination campaign across Gamilaraay country, involving roving bands of armed stockmen who hunted Aboriginal groups with impunity.

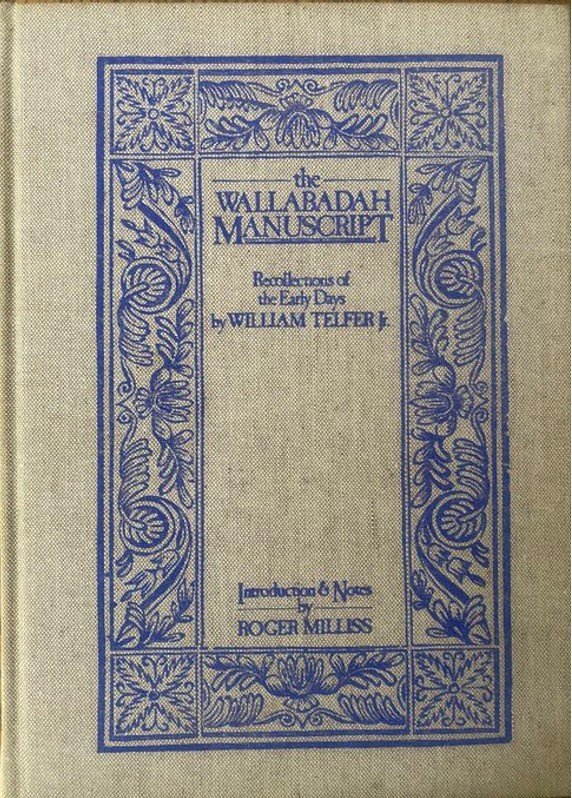

William Telfer, born in Scotland in 1812 and emigrating in 1833, worked as a stockman in these districts. He herded cattle across rugged terrain, built homesteads from local timber, and navigated the dangers of floods, droughts, and bushfires. Settling at Wallabadah near Quirindi by the 1870s, he compiled his manuscript from diaries and memories. Discovered in the 1970s and published in 1980 with Roger Milliss’s annotations, it spans 100 handwritten pages, offering unpolished insights into squatting, bushranging, and “black wars.” Telfer’s style – replete with spelling quirks like “Masacre” and run-on sentences – lends authenticity, positioning him as an observer, though his accounts reveal colonial biases. He romanticizes the pioneering life, describing vast herds and golden sunsets, but candidly admits to the violence that secured it.

The central quote summarizes 1838’s events, implying decisive defeat after “stubborn resistance.” Telfer details causes: “the stations on the Mcintyre were not long occupied when the aboriginals began to be very hostile and to be aggressive to the whites the cause was the Masacre of the blacks at slaughter house creek on the Big River where they ran the blacks into the Stockyard and destroyed them without mercy.” He links hostility to reprisals, inverting settler justifications that blamed inherent “savagery.” Other excerpts describe ambivalence: acknowledging grievances like land theft and interference with women while labelling Aboriginal actions “hostile.” Telfer recounts how Aboriginal warriors used guerrilla tactics, hiding in scrub to launch spears, forcing settlers to travel in groups. In the Maranoa extension into Queensland, Telfer recounts further killings, illustrating violence’s spread as squatters pushed north, encountering new resistance from groups like the Mandandanji.

Milliss contextualises the manuscript in revisionist history, challenging pioneer myths amid 1970s land rights movements. Historians use it to map extermination wars, estimating thousands dead in New South Wales. Its specificity – names of stations like Warroo, individuals like stockman John Eaton, dates of expeditions – aligns with oral histories and reports like magistrate Edward Denny Day’s 1838 accounts of “great numbers” killed at Slaughterhouse Creek, Vinegar Hill, and Gravesend. Day’s letters to the Colonial Secretary paint a picture of a “war of extermination,” where settlers boasted of their “drives” over campfires, sharing stories of narrow escapes and triumphant pursuits.

The Massacre at Slaughterhouse Creek: Emblem of Colonial Atrocity

The manuscript’s reference to 200 Aborigines killed in one massacre highlights Slaughterhouse Creek, a grim episode in Gamilaraay history. Between May 1 and June 7, 1838, at the Gwydir River junction (latitude -29.708, longitude 150.333), mounted stockmen from stations like Henry Dangar’s ambushed a camp. Armed with muskets, pistols, and cutlasses, they surrounded the site – a ravine or stockyard – firing at dawn and finishing with close combat. The attack began with the crack of gunfire echoing through the misty morning, startling the sleeping camp. Men, women, and children fled in panic, only to be cut down by volleys or pursued on horseback. Estimates reach 300 victims, including entire families, trapped in confined space ensuring few escapes.

Triggers included post-Waterloo Creek retaliations: spearing cattle and killing stockmen like those at nearby stations. Aboriginal groups viewed invaders as existential threats, disrupting hunting grounds and sacred sites. Settlers, feeling besieged in what they called “enemy’s territory,” responded disproportionately, boasting of “clearing the land” in letters home. Day’s 1839 testimony described dawn ambushes and volleys, with survivors hacked by swords. Folk lore speaks of whips herding victims like cattle, bones lingering for years, bleached by the sun and picked by crows. Local newspapers in the 1940s still referenced the site’s eerie reputation, with farmers avoiding it at night.

No prosecutions occurred; trials mentioned in local lore ended in acquittals due to legal technicalities, such as lack of witnesses or claims of self-defence. This impunity fuelled further violence, extending to Vinegar Hill (another 1838 massacre where dozens perished) and beyond. The event’s scale – potentially 200+ deaths – highlights the asymmetry: colonists’ guns and horses versus spears and boomerangs. Gamilaraay warriors, skilled in bush warfare, inflicted casualties but couldn’t match firepower.

Analysing through genocide studies, scholars argue it meets UN criteria: intentional destruction of a group in whole or part. The “stubborn resistance” in Telfer’s quote underscores Gamilaraay agency: organised defences by leaders using terrain knowledge. Yet, the “dying out” myth masked survivors who fled to fringes, preserving culture covertly through whispered stories and hidden ceremonies.

Similar patterns afflicted Wiradjuri lands. In the 1820s, martial law under Governor Brisbane targeted Wiradjuri warriors like Windradyne, who led raids after encroachments on the Bathurst plains. Massacres at sites like the Lachlan River decimated communities, with survivors scattered. Reserves confined them, suppressing practices, but oral traditions endured, passed in secret gatherings under the stars.

Broader Patterns of Violence and Myth-Making

The Wallabadah Manuscript reveals national patterns: over 300 documented massacres from 1788 to 1930, with 60,000-100,000 Indigenous deaths. These were not isolated but systemic, driven by economic imperatives. In Queensland, post-1838 expansion saw Maranoa killings, including 50 in 1850 under stealth tactics to avoid prosecutions like Myall Creek’s. Mandandanji leader Bussamarai united tribes with corroborees mimicking white defeat, rallying warriors with songs of defiance, but fell to Native Police in 1852 – a force of Aboriginal troopers from distant regions, coerced into service. Hornet Bank in 1857 prompted reprisals killing hundreds, with poisonings and drives clearing land for stations.

Government complicity was rife: mounted police amplified settler actions, providing official cover for private vendettas. Policies evolved to assimilation, confining Gamilaraay and Wiradjuri to reserves like Moree Mission or Erambie, where managers controlled movements and banned traditional languages. Children were removed to “civilise” them, breaking family bonds. The “dying race” myth, rooted in Social Darwinism, absolved guilt, portraying extinction as natural progression in the face of “superior” civilisation. Scientists collected artefacts and remains, treating living cultures as relics.

Denialism lingers: 2000s “history wars” questioned scales, with figures arguing exaggeration, but manuscripts like Telfer’s refute this through primary evidence. Projects mapping massacres document patterns, informing truth-telling in commissions and museums. Literature like Kate Grenville’s novels echoes these themes, humanising the conflict.

The violence’s legacy is profound: disrupted kinship led to social issues, but also forged resilience. Survivors adapted, working on stations while maintaining secret knowledge, laying foundations for revival.

Gamilaraay Resilience: From Survival to Revival

Contrary to Telfer’s claim, Gamilaraay people exemplify resilience, transforming trauma into empowerment. Their pre-colonial heritage – over 40,000 years – includes advanced systems: men hunting kangaroos and emus with boomerangs, women gathering yams and managing fires for regeneration. Spirituality centred on Baiame, with Bora initiations teaching laws and skills. Astronomical knowledge like the “Emu in the Sky” marked seasons, guiding mosaic burning and seed harvesting. Kinship moieties (Kupathin and Dilbi) and totems ensured sustainability, with trading networks exchanging ochre and tools.

Colonisation reduced numbers to 1,000 by mid-19th century through massacres and diseases like smallpox, but today over 30,000 identify as Gamilaraay. Resilience spans spiritual, social, educational, and economic realms, rooted in covert transmission during assimilation.

Language revitalisation is key: Gamilaraay-Yuwaalaraay, once endangered by bans in schools, thrives via elder-led classes, community workshops, and digital tools like apps with dictionaries and games. The NSW Aboriginal Education Consultative Group developed resources enhancing visibility. Language Nests provide immersion, creating jobs and boosting outcomes. Proficiency correlates with 20% higher post-school qualifications, improved self-esteem, and cognitive benefits like better attention. In 2018, Stage 6 syllabi enrolled 20 students, fostering aspiration. Wellbeing links are clear: speakers report stronger cultural ties, emotional health, and self-determination. Revival addresses trauma through truth-telling, empowering independent heritage preservation.

Cultural camps like “Gaawaadhi Gadudha” reconnect adults with lore, languages, traditional foods like witchetty grubs, medicines from eucalyptus, and landscapes. Focusing on significant sites, activities promote Country connection as protection. Strengths-based approaches challenge deficit views, using surveys (Connor-Davidson Resilience Scale) and yarning circles for insights. Evidence shows enhanced identity, resource access, emotional wellbeing, informing “Model of Cultural Health” for policies. Broader studies link engagement to reduced substance abuse, suicide, intergenerational trauma, while building pride and bonds. Camps align with Mayi Kuwayu frameworks, emphasising language and Country.

Healing intertwines resistance: individuals as warriors-healers address trans-generational trauma from Stolen Generations. Gamilaraay-led practices succeed where external ones fail. Dadirri (deep listening) connects inner spirits; returning to Country restores balance; learning songlines reclaims heritage; smoking ceremonies cleanse; embraces share spirit; song, dance, storytelling commune with ancestors. Clever Men healed removed kin, passing knowledge. Resistance fights systems using education, protects from mining, rejects assimilation, asserts sovereignty. This dual role builds strength.

Art and economics decolonize: fashion, media represent heritage; NAIDOC Week celebrates dances, stories. Poetry in First Languages engages youth, boosting identity. Revival creates teaching, tourism, arts jobs. Speakers earn from activities; collaborations apply knowledge to stewardship, like fire management. Elder-guided justice diversions reduce youth incarceration, promoting self-determination.

Benefits extend society: dual naming, ecological knowledge aid climate adaptation; arts reduce racism via understanding. Curriculum teaches patterns through stories, fostering inclusivity. Challenges: limited data, revival distress, mining threats. Institutions like AIATSIS preserve; Closing the Gap targets language by 2031.

Wiradjuri Resilience: Parallel Paths of Endurance

Adjacent to Gamilaraay, Wiradjuri resilience mirrors yet distinctively contributes to Indigenous revival. Their 60,000-year legacy includes semi-permanent villages, extensive trade, Baiame spirituality, totem systems, and Dreamtime stories encoding laws. Practices like controlled burning maintained ecosystems; tools like boomerangs reflected ingenuity.

Colonisation’s frontier wars and Protection Board devastated: martial law targeted leaders like Windradyne, massacres displaced. Yet, continuity evident in modified trees – stones embedded in bark for tools, a 2020 discovery showing 20th-century practice under assimilation.

Language efforts by Oyster Tribe build archives, classes, integrate into schools. Tied to Country and kinship, curricula foster transmission. Proficiency yields educational, emotional gains, countering loss.

Camps like “Healing Country” share management, addressing hazards through workshops on bush tucker, fire, storytelling. Strengths-based, using surveys and yarning, findings show wellbeing boosts, reduced risks.

Healing: Dadirri, ceremonies counter trauma; resistance advocates against mining, uses art reimagining identity – post-apocalyptic narratives empower.

Creativity: media, fashion; NAIDOC features poetry, dances. Wiradjuri Condobolin Corporation empowers via programs, sustainable ventures, jobs in tourism, education.

Gains: ecological adaptation, inclusivity via naming, empathy through arts. Challenges: data limits, strains, development threats. Heritage protects sites; Closing the Gap sustains culture.

Broader Implications: Myths, Reconciliation, and Legacy

Merging these narratives exposes colonial myths: “dying out” justified dispossession, but resilience proves otherwise. Socio-economically, violence entrenched inequality – poverty, health gaps – but initiatives like Closing the Gap target legacies, with mixed success in education and life expectancy.

Politically, the 2008 Apology addressed Stolen Generations; truth-telling commissions draw on manuscripts for healing. Uluru Statement calls for Voice, Makarrata, treaty. Globally, parallels with Canada’s inquiries, America’s movements highlight shared decolonisation.

In 2026, amid Voice debates, the manuscript demands acknowledgment: memorials at Slaughterhouse Creek, curricula including frontier wars, reparations through land returns. Gamilaraay and Wiradjuri use it in Native Title claims, proving occupation via oral evidence.

The quote’s “for Ever more” is hollow; Mabo overturned terra nullius in 1992, enabling claims like those returning parts of Wiradjuri Country. Challenges remain: mining on sacred sites, high incarceration, climate impacts on traditional lands. Yet, ethical history fosters justice, with youth leading revivals through social media and activism.

Conclusion

The Wallabadah Manuscript unmasks colonial brutality, centring 1838s subjugation and Slaughterhouse Creek’s horrors. Yet, Gamilaraay and Wiradjuri resilience – through language, camps, healing, art – reclaims sovereignty, ensuring continuity. This honours victims, critiques narratives, and advocates shared futures. Possession was never eternal; Indigenous endurance prevails, inspiring a reconciled Australia where truth paves the way for equity.